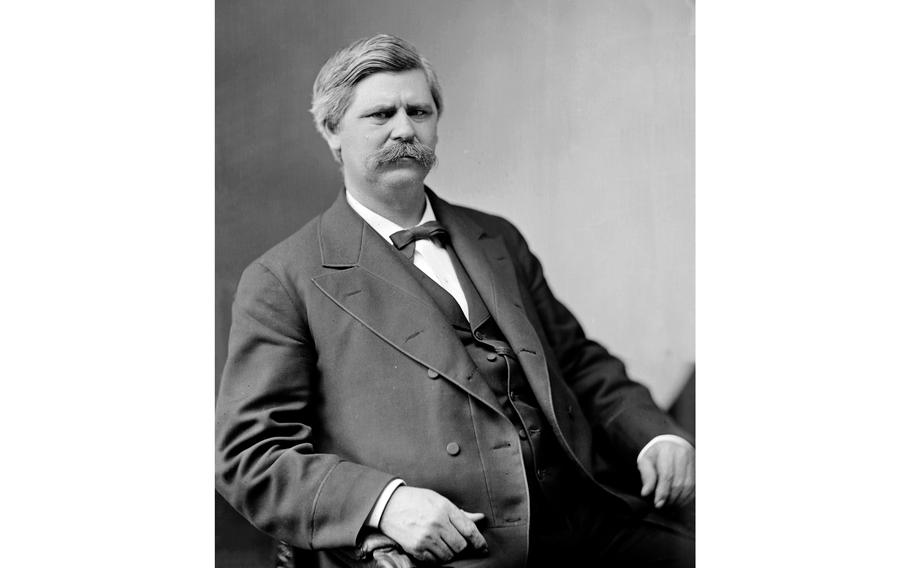

Sen. Zebulon Vance circa 1875. (Mathew Brady/Library of Congress)

A New Mexico judge ruled this week that a county commissioner was disqualified from holding office because he participated in the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

In ordering Otero County Commissioner Couy Griffin removed from office, the judge cited a section of the 14th Amendment disqualifying any elected official "who, having previously taken an oath … to support the Constitution of the United States," has then "engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof." The advocacy group that filed the lawsuit is also considering attempting to use it to disqualify former president Donald Trump from the 2024 presidential contest, according to the New York Times.

The disqualification clause, as it is sometimes called, was written in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, in the brief period when Radical Republicans — some of the most progressive lawmakers in American history — held a majority and were determined to stop high-ranking Confederate traitors from returning to public office.

The amendment doesn't specify who's supposed to be enforcing it, so the responsibility has fallen to different bodies. Griffin was disqualified in court, but historically, Congress itself has sometimes taken votes to prevent elected members from being seated.

Two of those instances highlight the inconsistency of the clause's application: The last time it was used successfully, nearly a century ago against antiwar lawmaker Victor Berger (who was not, by any standard definition, an insurrectionist), and when it was applied against former Confederate Zebulon Vance — who, like Berger, was allowed to waltz back into office once the political winds had shifted in his favor.

Vance grew up in a well-connected family that struggled financially but still enslaved more than a dozen people. After law school, he rose in the political ranks, first in the state senate and eventually as the youngest member of the 36th Congress, representing Asheville and the surrounding areas.

(Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R-N.C.), who currently represents Asheville and was also the youngest member of his Congress, faced a lawsuit trying to disqualify him from Congress under the 14th Amendment. The lawsuit was dismissed as moot after Cawthorn lost his primary in May.)

As the march toward the Civil War escalated, Vance initially opposed secession but eventually served in the Confederate Army. He also served as the Confederate governor of North Carolina.

After the war, in 1870, he was appointed senator from North Carolina, but the Senate refused to seat him, citing the 14th Amendment. After spending two years in Washington trying to get an amnesty, he gave up.

But only a few years later, Washington was handing out amnesty like candy, defeating the whole purpose of the clause. Vance got his in 1875 and was elected to the Senate three years later. Not only did he serve until his death in 1894; in a sense, he is still there today: A statue of Vance stands in National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, a 1916 gift from North Carolina that Congress cannot legally remove unless the state decides to replace it.

Berger had a very different story, though he ended up in the same pickle as Vance. Born into a Jewish family in the Austrian empire, he immigrated to the United States as a young man in 1878. He became a successful publisher in Milwaukee of both English- and German-language newspapers.

Berger was a leading voice of the "Sewer Socialists," who believed socialist objectives could be achieved through elections and good governance, no violent revolution necessary. Today, we would call this a "roads and bridges" platform; back then, it was working sewers and clean, city-owned water.

Berger served one term in Congress — the first-ever Socialist Party member — from 1911 to 1913, the high point being when he introduced the first bill for an old-age pension. (Nowadays we call that Social Security.) He didn't win reelection, but he stayed active in Wisconsin politics and in publishing.

Then World War I began, and with it came the First Red Scare. Berger was against the war and said so in his editorials, and in 1918 that was enough for him to be charged with "disloyal acts" under the Espionage Act. He was running for Congress again while under indictment, and soon after he won the election that November, he was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in federal prison.

While out on appeal, Berger showed up in Washington to be sworn in. The House refused to seat him by a vote of 309-1, saying his words had "given aid or comfort" to enemies of the nation, and he was thus barred under the 14th Amendment.

In December 1919, he ran in the special election to replace himself, and incredibly, he won. The House refused him a second time. In 1921, Berger's conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court, and he returned unfettered to Congress in 1922, where he served three terms, pushing legislation to crack down on lynching and to end Prohibition.