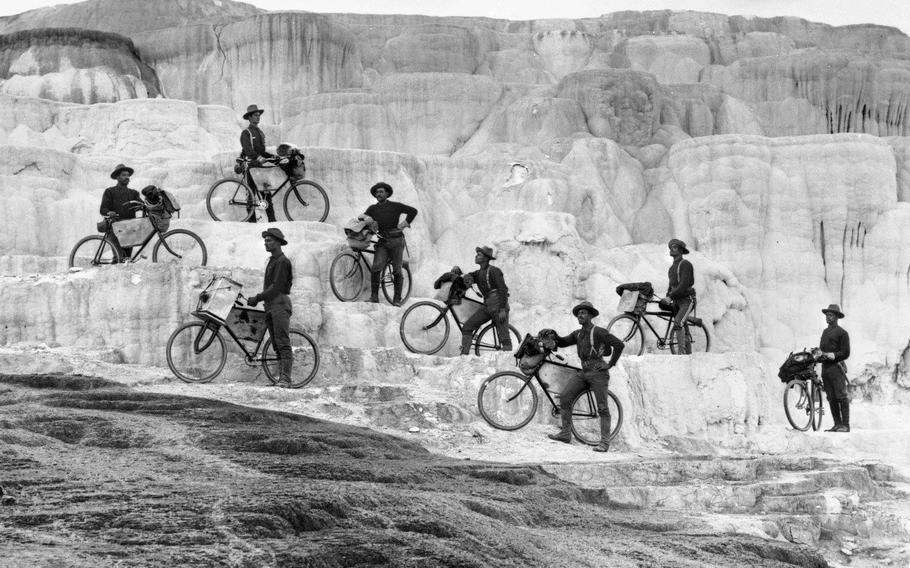

In 1987, the 20 Black members of the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps — Buffalo Soldiers, they were called — along with two officers and a reporter rode up and over the mountains of Montana, across Wyoming and Nebraska and all the way to St. Louis, where they were met by an estimated 1,000 civilian cyclists and accompanied to a parade in their honor. (Facebook)

(Tribune News Service) — As the sun was rising on June 14, 1897, a group of soldiers in southwest Montana straddled their bikes and turned their handlebars east.

They were about to spend the next 41 days, 1,900 miles and endless hardships — mountain sleet, Nebraska heat and tire-sucking Sandhills — trying to prove their young lieutenant's point:

That, by the turn of the last century, the bicycle was an effective way to transport U.S. troops.

The 20 Black members of the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps — Buffalo Soldiers, they were called — along with two officers and a reporter rode up and over the mountains of Montana, across Wyoming and Nebraska and all the way to St. Louis, where they were met by an estimated 1,000 civilian cyclists and accompanied to a parade in their honor.

Their lieutenant was pleased. His so-called Iron Riders had averaged nearly 56 miles a day and more than 6 mph, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

But it hadn't been easy. Fully loaded, their single-speed bicycles weighed nearly 80 pounds. They battled bad weather and bad water and roads that were rocky, muddy, sandy or non-existent.

They suffered in the Sandhills after they left Alliance.

"Indeed, our experience in these hills was the stuff of which nightmares are made!" the lieutenant wrote. "It was impossible to make any headway by following the wagon road in loose sand … and we therefore followed the railroad track for 170 miles before getting out of the sand."

After one of those hard days, as his soldiers were waiting for their meal, the lieutenant heard one declare: "Oh Lord, if I only live through this, I'll have something to talk about as long as I live!"

More than a dozen decades later, Erick Cedeno is living through it.

The 48-year-old cyclist from California left Missoula, Mont., at 5:40 a.m. on June 14 — precisely 125 years after the Iron Riders — with plans to roll into St. Louis July 24.

Erick Cedeno is retracing the route that the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps rode from Montana to Missouri 125 years ago. (Facebook)

He started making cross-country trips more than a dozen years ago — Vancouver, British Columbia, to Tijuana, Mexico; Miami to New York; retracing the Underground Railroad.

At the time, he also started thinking about, and researching, early long-bicycle explorers near the last turn of the century.

They were all white.

"And then I came across this history of the Buffalo Soldiers," he said, taking a break in Grand Island before pedaling to York. "I got fascinated as a person of color, because I hadn't seen anyone of color traveling by bike back then. That didn't mean it didn't happen; it just wasn't documented."

The Army's effort was recorded, though, so he was able to gather enough details to plan to retrace their trip.

He took a year off from the road in 2021 — he and his wife had a son — but he told her he wanted to honor the soldiers this year, the 125th anniversary of their expedition.

"And she said, 'You must, because their legacy must continue. You've got to tell their story, and it's part of your legacy, too."

He has it easier than the Iron Riders. His bike weighs a fraction of what theirs did, and he has gears, and pavement beneath his tires.

He's dealt with similar weather — cold in the mountains, heat on the Plains — but he can get a motel room when he needs Wi-Fi, or when he doesn't feel like making camp.

Still, he can imagine what they endured. "It's one thing reading how grueling it was, but it's another thing doing the ride. What they did was almost superhuman; as strong as a rider I am, I probably wouldn't have been able to do that under those conditions."

Cedeno spoke about the expedition at a museum in Wyoming, and has talks planned in Lincoln and Missouri. But even after the ride, his research will continue, he said.

All of the documented accounts are told through white perspectives — by the two officers, and the journalist.

He wants to give voice, and due credit, to the Iron Riders who volunteered for the trip and helped prove their lieutenant's point.

"It was a sense of pride to know these Black soldiers in 1897 did this amazing trip. I want to pass that history along, and not let it die."

To follow Cedeno's trip, go to facebook.com/bicyclenomad

(c)2022 Lincoln Journal Star, Neb.

Visit at www.journalstar.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.