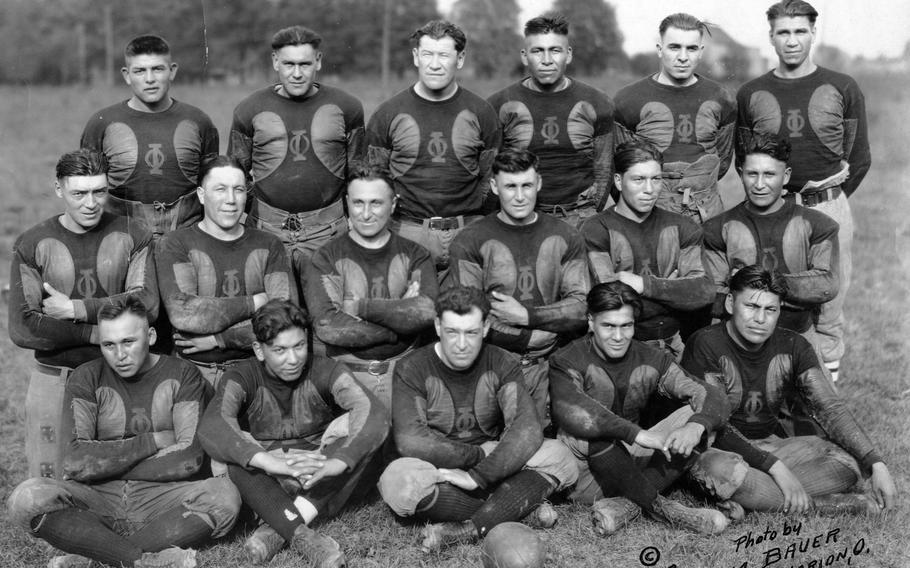

The Oorang Indians played in the NFL in 1922-1923 and had all Native American players, including Olympic star Jim Thorpe, third from left in back row, as a player-coach. (Adam Bauer/Courtesy of Cumberland County Historical Society in Pennsylvania)

On Wednesday, Washington's National Football League team will unveil its new name, following a lengthy campaign by Native American activists to abandon an identity long seen as a racial slur.

Largely forgotten in the controversy over Native American-derived team names is the story of a short-lived NFL franchise founded 100 years ago and composed entirely of Native American players.

The Oorang Indians played two seasons starting in 1922, led by the famous Olympian Jim Thorpe. The team concept might seem progressive - its name and stereotypical halftime shows, less so.

The team started when Walter Lingo, a businessman in LaRue, Ohio - population 795 - paid $100 to the newly formed NFL for a franchise. It put LaRue on the map, making it one of the smallest cities ever to have an NFL franchise.

An avid outdoorsman and dog lover, Lingo became fond of Airedales, a breed of terriers. Lingo started to breed his own Airedales from a stock called Crompton Oorang and eventually established a major dog kennel. In 1913, he named his dog-breeding business the Oorang Kennels.

Lingo had another interest: Native Americans. Like many people of his time, he grew up with a romanticized view of American Indians and the Wild West, and his father had told him that American Indians had an intuition about dogs and could "spot certain characteristics" in training them, according to Chris Willis, author of "Walter Lingo, Jim Thorpe, and the Oorang Indians."

Lingo combined his two passions - dogs and Indians - and named his football team after them. For him, the team was largely a publicity stunt for his dog-breeding business, according to Native American historians and authors who have written about the Oorang Indians.

He invited his friend Thorpe, who had briefly served as the first president of the American Professional Football Association - which later became the NFL - on a hunting trip and made him an offer: become a player-coach on this newly formed NFL team and supervise the training of Lingo's dogs at his kennel. The pay was $500 a week.

Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma, was in his 30s and at the height of his stardom. He had became a household name as the first Native American gold medalist for the United States in the Olympics in 1912, winning the pentathlon and decathlon. He then played baseball for the New York Giants, Cincinnati Reds and Boston Braves. He also played professional football with several teams, including the Canton Bulldogs and Cleveland Indians, both in Ohio.

Thorpe was considered one of the most talented and versatile athletes of his time. The Associated Press would later name him the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century, and he would be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

He accepted Lingo's offer. Lingo thought an all-Native American team would generate publicity, so he and Thorpe recruited 18 Native American football players. Many of them had played with Thorpe at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, one of the first government-run boarding school in the country and a football powerhouse that played teams including Harvard and Penn State. (Carlisle was also known for mistreating Native American children who were taken from their homes and forced to stop practicing their tribal customs.)

For the Oorang Indians, Thorpe helped attract larger crowds, on average, than most NFL teams, Willis wrote. The team played almost all of its games on the road in bigger cities such as Buffalo, Chicago, St. Louis and Toledo, as LaRue didn't have a stadium that was large enough.

"Everybody in those days knew who Jim Thorpe was," said Juaquin Hamilton, a historical researcher for the Sac and Fox Nation. "Lingo was using the team - and the players - to advertise his breed of dogs. He was using Native American athletes to advertise his dogs."

Sales of Lingo's Airedales jumped to record levels, hitting 15,000 one year. He became known nationwide as the "King of Dogs."

The Oorang Indians had other talented players, including Joe Guyon, a Chippewa from Minnesota who became a Hall of Famer, and Pete Calac, a Mission Indian from California who had played for the Canton Bulldogs, Cleveland Indians and Washington Senators.

On the field, many of the players used their native name or nickname Thorpe gave them. Lone Wolf, Red Fang, Running Deer and War Eagle were all Chippewas from Minnesota. War Horse, a Mohawk, and White Cloud, a Seneca, came from New York. Tomahawk was a Wyandotte Indian from Ohio, and Red Fox was a Cherokee from Oklahoma. Thorpe's native name was Wa-Tho-Huk, which meant Bright Path.

One player, Joseph Pappio, told a reporter with the Oklahoman in 1962 that growing up on the Chippewa reservation in Minnesota, he'd heard "lots of stories about the greatest athlete of all time, Jim Thorpe." He said as a kid he wanted to be like Thorpe, so he eventually enrolled at Carlisle. When Thorpe later asked him to join the Oorang Indians, he agreed.

Pappio's grandson Joe Poe Jr. recalled hearing stories of his grandfather playing for the Oorang Indians. "There's a story that my grandpa would hit people so hard they'd lose their helmets," he said.

Poe said he didn't think the team's name was inappropriate. "Back then I don't think there was any offense taken at it," he said. "It was just a different time."

The team became known for creating what was probably the first football halftime show. Lingo's Airedales would chase live raccoons up fake trees, showing off their hunting skills. The Native American players would perform a dance that conformed to White audiences' expectations from Wild West shows, according to several sports and Native American historians. The players put on feathers, danced to a drum, and tossed tomahawks and knives for entertainment. One of their occasional stunts was to reenact World War I battle scenes with Lingo's Airedales, where the dogs delivered first aid to wounded Indians who were scouts against the Germans.

The shows became such a pageant that "people joked, 'Is it a dog show with football or a football game with a dog show?' " said Dave Zirin, author of "A People's History of Sports in the United States" and the sports editor at the Nation magazine.

"It seemed like [Lingo] was making a mockery of Native culture by having natives put on shows of stereotypes that are harmful to us," said Katie Thompson, the language director of Thorpe's tribe, the Sac and Fox Nation.

Though the halftime shows were probably demeaning for the Indian players, "they knew, 'We're performing Indianness,'" said Philip J. Deloria, a Harvard historian who is of Dakota descent.

"They understood performing was a good work opportunity in a constricted life and labor market, and the trade-offs were worth it," Deloria said.

Leon Boutwell, a Chippewa quarterback for the team, was asked at the time how he thought White audiences viewed the all-American Indian team. He explained to a reporter, "White people had this misconception about Indians. They thought they were all wild men, even though almost all of us had been to college and were generally more civilized than they were."

He added, "Well, it was a dandy excuse to raise hell and get away with it when the mood struck us. Since we were Indians, we could get away with things the Whites couldn't. Don't think we didn't take advantage of it."

In 1923, the team folded because Lingo - and the team's fans - had lost interest. "He wasn't in the business of winning games or fielding a competitive team," Willis wrote. "He was in the business of selling dogs." Lingo and Thorpe agreed "the idea had run its course."

The team's record over its two seasons: 4-16.

Few historians even know of the Oorang Indians team, Deloria said, and that's in large part due to a "settler colonialism" and a "long-standing tradition of taking Native people of out of larger stories of American history."

A century later, the team name would probably not be tolerated, Deloria said, but in the culture of the 1920s, it was probably not considered offensive among the mostly White spectators who filled the stands.

"If you said today, 'Let's combine Indians and dogs and make it a football team's name,' we'd be like, 'Holy moly, that's offensive and feels insane,' " he said. "But we've had decades to think about this stuff and to analyze it and step back."