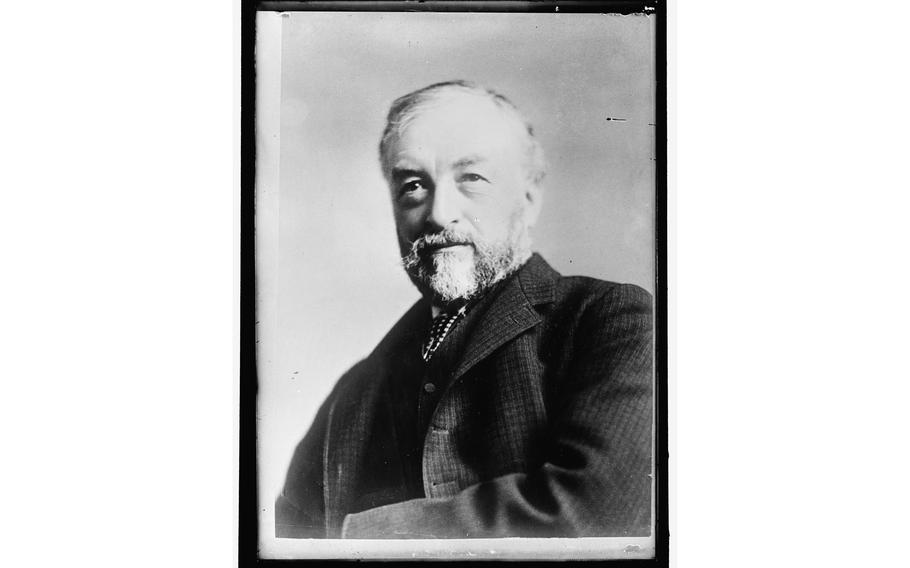

Samuel Pierpont Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, with an experimental biplane on the Potomac, c. 1917. (Library of Congress)

The label on the aircraft displayed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., read: "The first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight. Invented, built and tested over the Potomac River by Samuel Pierpont Langley in 1903."

Wait. Didn't the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright invent the airplane?

That's what an angry Orville Wright, the surviving Wright brother, protested in 1925. The label, put on display a few years earlier, set off a nearly 20-year feud between the Smithsonian and Wright. The dispute's roots went back to the very birth of flight.

In late 1903, the Wright brothers and Langley, the Smithsonian's director, were racing to be the first to fly a powered aircraft. The 69-year-old Langley, an astronomer and inventor financed by federal funding equal to $1.6 million today, worked out of a spacious laboratory in the Smithsonian Castle on Washington's National Mall. The Wrights, operating on a shoestring budget, labored in their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, and a field in North Carolina. Both brothers were in their 30s.

Samuel Pierpont Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, c. 1917. (Library of Congress)

Langley was first to try to get his flying machine off the ground. The machine, called "The Buzzard" (and also referred to as the Aerodrome A), was 60 feet long with two 48-foot wings. The plan was to catapult the plane into the air from a houseboat on the Potomac River near Widewater, in Stafford County, Va.

On Oct. 7 at 12:15 p.m., the machine was launched with Langley's assistant aboard. The "mechanical bird . . . took the air fairly well," the Washington Star reported. "The next instant the big and curious thing turned gradually downward." Then "all was wreck and ruin." The aerodrome crashed into the Potomac, a hundred yards from the houseboat.

This "would not in any sense be termed a 'flight,'" the Star concluded.

Langley tried again on Dec. 8 on the Potomac in Washington. A large crowd turned out to watch the history-making event. This time, on launch, the machine did "a half double somersault" and crashed into the water "broken and twisted into a mass of wood, steel and linen, with its nose in the mud on the river bottom," the Star reported. The press dubbed the machine "Langley's Folly."

Then, on Dec. 17, Wilbur Wright and his younger brother, Orville, tested their flying machine, the Wright Flyer, in a field in Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, N.C. It was a biplane with a rudder in the middle over a gasoline engine. Orville, who weighed less than 150 pounds, was at the controls, lying flat on his stomach.

The plane taxied, lifted off and "soon had attained a height of 60 feet above the rolling sand dunes," the Dayton Daily News reported. The plane flew against a 27-mile-per-hour wind "without difficulty and maintained an average speed of eight miles an hour with ease."

A "small crowd of fish folks and coast guards" followed beneath the plane "with exclamations of wonder, but it soon drew away from them," the paper said. Soon Orville "let his machine alight as easily and as gracefully as a bird."

The plane had flown for 12 seconds and a distance of 120 feet. It was the first successful airplane flight in history. The brothers flew their invention three more times. The longest flight was 59 seconds and 852 feet, with Wilbur at the controls. Afterward, Orville wired back to Dayton: "Success: Will be home for Christmas."

The brothers soon made planes that could fly considerable distances, and they became world-famous celebrities. A photo of Wilbur flying a plane around the Statue of Liberty in 1909 ran on the cover of Harper's Weekly above the headline "A NEW KIND OF GULL IN NEW YORK HARBOR."

Langley died in 1906, some said of a broken heart; Wilbur died six years later of typhoid fever. In 1914, new Smithsonian director Charles Walcott, an old friend of Langley, had Langley's flying machine restored and tested by Glenn Curtiss, a pilot and aviation manufacturer whom the Wrights had sued for patent infringement. (In 1922, a federal appeals court ordered Curtiss to pay the Wrights royalties because their patent covered all controlled flying machines. The companies founded by Curtiss and the Wrights later merged.)

Curtiss concluded that the plane had been capable of flight; the problem had been the catapult. In 1918, the Smithsonian put the restored Buzzard on display at the National Museum, and over the years Walcott revised the label to call Langley's invention the first airplane.

The 1903 Wright Flyer currently on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. (Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum)

Orville Wright did not take this one lying down. In a 1925 public letter about the Smithsonian's Langley exhibit, Wright asserted that "the machine now hanging in the institution is, much of it, new material and some of it of different construction from the original," and "the card attached to the machine is not true of the original machine or of the restored one."

Wright set off a national firestorm by revealing in his letter that he planned to send the Wright Flyer to the Science Museum at South Kensington in London. "No one could possibly regret more than I do that our machine must go into a foreign museum," he wrote.

The Smithsonian refused to budge. Congress held hearings. Republican Rep. Roy Fitzpatrick of Ohio called the institution's stance "an outrage against the Wright brothers and an attempt to cheat them out of the victory of their discoveries."

In 1928, new Smithsonian director Charles Abbot issued a statement offering to revise the offending label, but only "if Mr. Wright will openly state in a friendly way" that "he believes that the Langley machine was capable of flight under its own power." Wright considered the offer an insult and shipped off the Wright Flyer.

Finally, in 1942, the Smithsonian caved under pressure. It reported that Abbot had "tendered sincere apologies to Dr. Orville Wright for misleading statements by former Smithsonian officials," and it said if the Wright plane were sent to the Smithsonian, it would be given "the highest place of honor which is its due."

On Dec. 17, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced, "I am glad to be able to tell you that Orville Wright is going to bring the Kitty Hawk plane back from England where it has been in the British Museum. The nation will welcome it back as the outstanding symbol of American genius."

Until the end of World War II, the Wright plane was stored safely in an underground chamber about 100 miles from London. Before the plane could be returned, Orville Wright died of a heart attack in January 1948. He had seen plane speeds go from 6.8 miles per hour on his first flight to 662 mph in 1947, when Air Force Capt. Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier.

The Wright Flyer finally was unveiled at the Smithsonian's Arts and Industries Building on Dec. 17, 1948. Its placard read: "The world's first power-driven, heavier-than-air machine in which man made free-controlled and sustained flight, invented and built by Wilbur and Orville Wright . . ."

In 1976, the Wright plane moved to a place of prominence in the new National Air and Space Museum. In the fall of 2022, the museum plans to open an expanded exhibit focusing on "The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Aerial Age." A century after infuriating Orville Wright with its plaque crediting Langley for inventing the airplane, the Smithsonian is all in on celebrating the Wrights for the accomplishment. (A museum official noted that the new exhibit will include a unit on Langley and the Smithsonian-Wright controversy.)

But Langley was ultimately recognized for his research, if not for inventing the airplane. Langley Air Force Base and NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va., are both named after him.