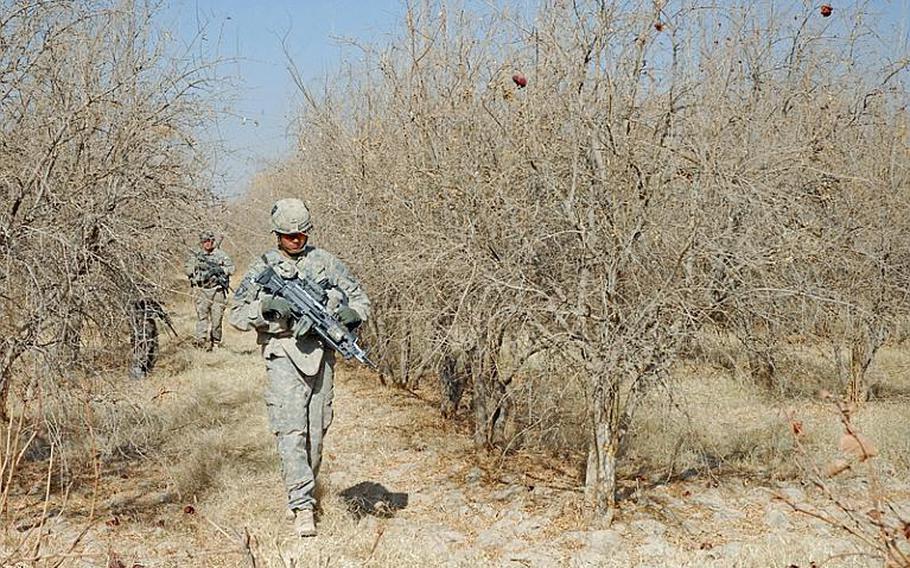

A 101st Airborne soldier patrols through the barren pomegranate fields in the Zhari district of Kandahar in December. The insurgents desert this area each year when the leaves fall off the trees, taking away the dense foliage they use for cover in the summer. This makes it hard for the military to judge the success of their massive clearing campaign this fall. (Megan McCloskey/Stars and Stripes)

KANDAHAR, Afghanistan — Despite Gen. David Petraeus’ optimistic assessment of the war’s progress in a letter to troops last week, military commanders on the ground here in this pivotal province openly admit they can’t yet judge whether their operations have the insurgents on the run or whether it’s just the winter that has brought calm.

“It’s way too early to say we’re being successful,” Maj. Curt Rowland, the operations officer for 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, which operates in the Zhari district of Kandahar, said recently.

Clearing operations in Kandahar are largely complete, but leaders say they won’t be able to measure success until fighting season begins again this summer.

“We’ll start getting some answers come June or July,” said Maj. Gen. James Terry, the top commander in the area.

It’s the same cycle of fighting that has dominated the Afghanistan war effort since the start — lulls in the winter, fierce battles in the summer — but for the first time, Washington is clamoring for measures of progress and the military is running out of time with a July deadline to begin troop withdrawal.

The vexing question remains: Is Kandahar, spiritual home of the Taliban, safer for good or simply safer for now?

“The enemy will come back,” Petraeus said in a December interview with Stars and Stripes. “We know that.”

What remains to be seen is what kind of reception the insurgents will get from the locals and how effective the insurgents will be in re-establishing fighting positions. That’s what will define the success of 2010’s fall offensive in the province, Petraeus and others have said.

Maximizing gains

In Zhari, the Army is hedging its bets, pulling a scheme from the Baghdad playbook by building a 12-mile-long concrete wall to fortify its front lines.

The military is being careful about how much they try to hold, worried that taking on too much ground would leave them vulnerable to Taliban resurgence.

On the western end of the district, the 2-502nd, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division has focused on the populous area directly south of Highway 1, a major route that circles the country and connects the Helmand River Valley to Kandahar City.

The Taliban had an entrenched fighting position there with bunkers and tunnels that took advantage of the grape fields — row upon row of dirt mounds substituting for trellises. When the clearing operations started in September, it took the unit three days to make its way just over a half-mile south.

Commanders don’t want to have to fight in that area again, so they’ve calculated that it’s worth stopping to solidify gains.

“I fully expect the enemy to come back and hit us as hard as they can in spring,” Rowland said.

The 2nd BCT commander, Col. Art Kandarian, wouldn’t say whether the Army could hold the territory it has now without the wall.

Commanders would only say they’re trying to maximize gains in one area as much as possible. They figure if they create a psychological and physical barrier between the residents and the Taliban — build what they are calling a gated community — then they can improve security enough that the Taliban can’t come back.

101st Airborne soldiers patrol in western Zhari through grape fields with vines that are dead for the winter. The military says it won't be able to judge the success of its fall clearing operations in Kandahar until the grape and pomegranate fields are once again lush, harkening the start of the traditional fighting season. (Megan McCloskey/Stars and Stripes)

Capt. David Yu, Company B commander with 2-502nd, said the wall helps people know they are safe.

“It sends a big message,” he said. “The wall is a way we can show them there’s increased security.”

From a military standpoint, “it creates a place where we can focus our security efforts up front and work on holding and building in the back,” said Capt. Timothy Price, commander of 2-502nd’s Company D.

The strategy appears to be working, commanders said. An increasing number of residents behind the wall have been reporting Taliban activity, pointing out roadside bombs and weapons caches and asking for government-issued ID cards so they can ditch the ones the Taliban gave them.

How far the Army can push into Taliban territory south of the wall and hold the ground taken, leaving behind only ANA in the swath they already cleared, depends on the intensity of the fight this spring. If the Taliban are back in force, the ANA are unlikely to be able to hold the area by themselves, hampering the Army’s ability to take more ground without additional forces, commanders here said.

‘They have no idea’

In addition to the tenuous security, public services in Zhari are almost nonexistent. There are no schools, the government is only a third staffed and locals are largely ignorant of national developments. One startling example: Some residents have told troops they didn’t know the Afghan National Army existed.

As one soldier said, “This is the ’hood. They have no idea what governance is.”

In an area with deep sympathies for the Taliban, the insurgent propaganda campaigns are also widely believed, making villagers suspicious of the coalition’s motives.

On a patrol earlier this winter, 1st Lt. Sayre Payne, a platoon leader with 2-502nd’s Company D, stopped to talk to a village elder for the first time. The man quickly interrupted Payne’s usual meet-and-greet banter, demanding to know how he felt about Islam and what, exactly, his intentions were regarding the villagers’ beliefs. Payne soon learned the Taliban had told the villagers the Americans were on a crusade to convert them to Christianity.

The deeper into long-established Taliban territory, the more reticent villagers are to believe and trust the coalition, said Col. Mark Stevens, who heads 2nd Brigade’s human terrain team.

In general people are paranoid, Price said. If they don’t recognize another Afghan, they assume he’s Taliban.

After years of watching coalition forces come into Kandahar only to later abandon them, leaving them prey to a vengeful Taliban, people are skeptical that the Army is here to stay.

Nearby in western Arghandab, relics of past attempts at development litter the area. A Japanese-built school from 2004 is now a shell of a building, long abandoned by everyone except the insurgents and their bombs. There’s a gutted health clinic that had been rigged to blow.

The 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team found entire villages that had been taken over by the Taliban. As villagers who had fled slowly returned at the end of the fall clearing campaign — not just in Arghandab but across Kandahar — they told soldiers they would only cooperate if there were guarantees the military was going to stay through the next fighting season.

Soldiers think many of the villagers are playing both sides, unwilling to commit to either until there’s a clear winner.

The Arghandab residents seem to be “waiting until spring to see what’s really going to happen,” said Lt. Col. David Flynn, 1-320th commander.

Signs of success

Even though success can’t be measured yet, there are signs of enduring changes, said Brig. Gen. Andre Corbould, a deputy commanding general for Regional Command South.

The Eid al-Fitr celebration this fall, which marks the end of Ramadan with festivals, went more smoothly than the coalition had seen before in Kandahar City, Corbould said.

At many of the major markets across the city there, stall owners are making capital investments in improvements, Henry Ensher, top civilian in RC-South, said. Any time business owners are willing to commit “in ways they can’t instantly recoup their money” is a good sign, he said.

Maj. Gen. James Terry, commander of troops in southern Afghanistan, visits the village of Malajat, just south of Kandahar City in January. Asked what he thought of the area’s progress toward stable security, he said “I think we’ll know more in July.” The military says although signs look promising it can’t yet judge the success of clearing campaigns across Kandahar. Not until the fighting season begins again this spring will they start to have answers. The lieutenant colonel showing Terry around commented that in the summer the area is beautiful — deadly — but beautiful. “Hopefully not this summer,” Terry replied. (Megan McCloskey/Stars and Stripes)

At one of those markets in January, a shopper said that because of improved security, his father and brothers had recently moved back to the village in Panjwai that they had abandoned. He was staying in the city because his job as a driver is profitable — both solid signs that people are feeling comfortable with the long-term prospects of security.

Kandarian highlights as a success the revitalization of the Howz-e-Madad market in Zhari, at one time the largest in the province outside Kandahar City.

“Seeing women and children in the Howz-e-Madad bazaar is a big deal,” he said.

Another key success is Highway 1, which was under de facto Taliban control for three years. The route was littered with roadside bombs and was attacked throughout the day. FOB Howz-e-Madad, which sits along Highway 1, was a daily target this summer. The Taliban launched mortars at the base, and there were gunbattles anytime soldiers stepped out of the gate.

After three months of brigadewide clearing across the Zhari district, Highway 1 is largely secure. In the last few months there have been only a handful of attacks. That holds true on the highway throughout Kandahar.

The number of attacks always drops in the winter, Corbould said, but this time the decline has been much more significant.

Driving down a key road that runs south from the highway in December, Pfc. Aaron James, with 2-502nd, remarked on how casual it felt to using the road.

“Four months ago, it was go to [Morale, Welfare and Recreation], tell your family you love them,” James said. “Guys would be shakin’ and scared, thinking this was the end. It’s amazing to see how quick we’ve made progress.”

Mission critical

Leading up to the fighting season that will decide so much makes the winter critical.

Petraeus told troops that this fall was the first time the resources were right in Afghanistan. But with President Barack Obama’s commitment to start troop withdrawal this summer, along with the impending end of Canada’s combat mission in Kandahar, there is a realization among ground commanders that this is the best that resources will ever be.

“From a security perspective, we’re never going to have as many troops as we have now,” Canadian Brig. Gen. Dean Milner, commander of Task Force Kandahar, said. “We must drive forward.”

The coalition needs to make maximum use of the winter period to achieve governance programs that are sustainable in the summer when the trees are in bloom and it’s the thick of fighting season, Ensher said. They are focusing on connecting villages to the district government, leaving higher-level coordination of districts with the provincial government for later.

Brig. Gen. Kenneth Dahl, in charge of stabilization for Regional Command — South, expects midlevel Taliban commanders to return to Zhari, Arghandab, Panjwai and other traditionally sympathetic areas in Kandahar to recruit villagers for their summer offensive.

It’s a risk to turn the Taliban down, Dahl said, so this winter is about providing strong alternatives:

“What do we need to do that’s going to inspire that guy to say ‘no’?”