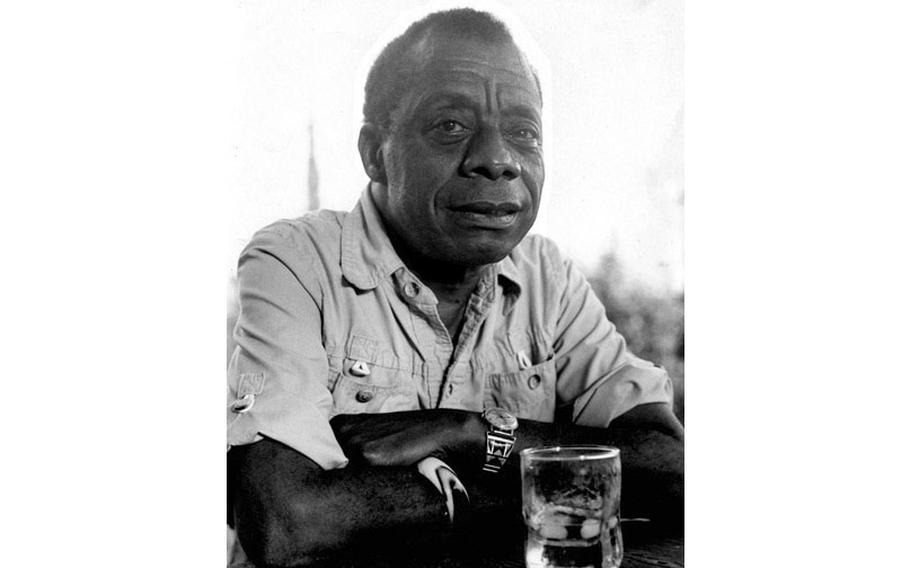

Author James Baldwin at his home in France in 1985. (Ed Reavis/Stars and Stripes)

SITTING AT A LARGE, rustic table under the thatched roof in the garden of his home in St. Paul, France, James Baldwin, 61 years old and the author of 19 books, sips a beer and sums up his present situation.

"I'm an elder statesman now," says Baldwin, who has spoken out on the black condition in America since his first book, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was published in 1953. "That's better than being 'a promising young black writer.'"

Just now, Baldwin is putting the finishing touches on his new book, Evidence of Things Not Seen, about the murders of 28 young Atlanta-area blacks from 1979 to 1981. Wayne B. Williams was convicted of two of the killings in April 1982.

BALDWIN'S BOOK will be published in Paris in September and in the United States In October.

"It was a very rough book to do. It was not the research that was so difficult, but dealing with being in Atlanta at that moment, which ultimately stretched over a period of years. And, you know, it's difficult to deal with your own feelings about dealing with the mother or the father of the missing or murdered child.

"You really don't realize how deep those feelings are until you confront them. What are you going to say, what are you going to ask? Then there are the social, economic and political ramifications of the case, which, in a way, is what the entire book is about."

When he works, James Baldwin comes to St. Paul. It's where he keeps his typewriter, he says.

"I've been coming to France for more than half my life, actually," said Baldwin, who has also written Notes of a Native Son, Giovanni's Room, Going to Meet the Man and If Beale Street Could Talk.

"I first came to France in 1948 in the wintertime. I stayed until 1952 — until I finished my first novel. I then went back home — but I guess the best way to put it is that I lived in Paris and went home two or three times until 1957."

THAT YEAR BALDWIN returned to the United States. The racial situation in the South concerned him, and he wanted to see conditions firsthand. Since 1970 he has commuted between Europe and the United States.

The relative privacy of St. Paul, a village perched 14 miles above the seaside resort of Nice, appeals to Baldwin.

"Here you're alone. You can never take a walk in New York and be alone, really. Central Park is an obstacle course. You just don't walk through Central Park trying to figure out the last chapter of your new book. In any case, I cannot."

Baldwin said he finds life in America very tense and above all, very public.

"You have to reconcile yourself to the fact that there is nothing you can do about it. At the same time you have to protect yourself. So this is where my typewriter is. This is where I really work. This is where I take off my shoes and don't have to answer the phone."

Baldwin came to France to escape. "As we black folk put it, I was always in the wrong neighborhood — and you pay for that ... It seemed clear to me that it was time for me to move, partly because I am the oldest of nine children. I was young, they were younger. My father was dead and the whole idea of becoming a writer was very, very, very doubtful. But that was the only hope I had, and I wasn't going to be able to do it if I spent all my time reacting to landlords that didn't want me to live there, reacting to policemen, reacting to ... you see, you get the picture."

BALDWIN ARRIVED in Paris with $40 and a one-way ticket, knowing nobody and no French.

"But a boy of 24 does that when he's really been pushed somewhere. And why Paris? I don't know — Richard Wright was in Paris, but I didn't expect anything from that. I knew some people in Paris, but I had not seen them for years.

"I did expect to find out who I was as distinguished from what I was. After that I felt I could take it from there."

BUT THINGS HAVE CHANGED since Baldwin fled to Europe.

"Europe is no longer the center of the world — that's part of the Western crisis. I came to Paris because I never would have thought of going to Latin America and there was no possibility of going to Africa. My generation would have almost automatically thought of Europe, Paris or London because of Charles Dickens, because of Balzac and all that. Europe was the only place that was 'Civilized,' with a capital C."

But, he said, that frame of reference is no longer valid for a 24-year-old black parson.

"The world is much much larger than it was. Options are greater. They're also dangerous, but options always involve danger. It's part of the crisis in Western psychology — the world is changing and there's nothing they can do to stop change. No one can hold on to the past. You have to use the past to deal with the present and create the future."

As a "senior statesman," Baldwin is swamped with manuscripts from young black writers, and he tries to do his best in reading them and getting them to good editors and publishers.

BUT THE BOOM of black literature of the late 160s is over, Baldwin said, and he called that boom a vogue, a convulsion of some kind on the part of American publishers.

Indeed, Baldwin believes the entire American publishing scene has changed, much to the detriment of literature.

"And how things have gotten much more difficult for a young black kid, or for a young white kid, for that matter. The publishing scene has become so completely commercial with the flourishing of non-books (diet books, how-to-do books, etc.) that he or she is faced with a very different scene from when I came down the pike.

"There were some real publishers then, and there were some real editors. And no doubt there are still some editors left someplace, but a great number of the ones I know are out looking for jobs. The publishing world is more and more in the hands of big business. There are, of course, exceptions."

Baldwin said a young writer needs nourishment. In his case, Baldwin said, it came from his family.

"It was a real connection which prevented me from going on the needle or drinking myself to death — just going under. I didn't want the kids to be ashamed of me. That may have been the margin.

"The community in which I grew up in Harlem was a community — none of that is true anymore anywhere in the United States. So the kid is almost in limbo from the get-go — man or woman. And the same difficulty that I had relating to black people and relating to white people would still be true now. There's almost no difference — the bottom line hasn't changed."