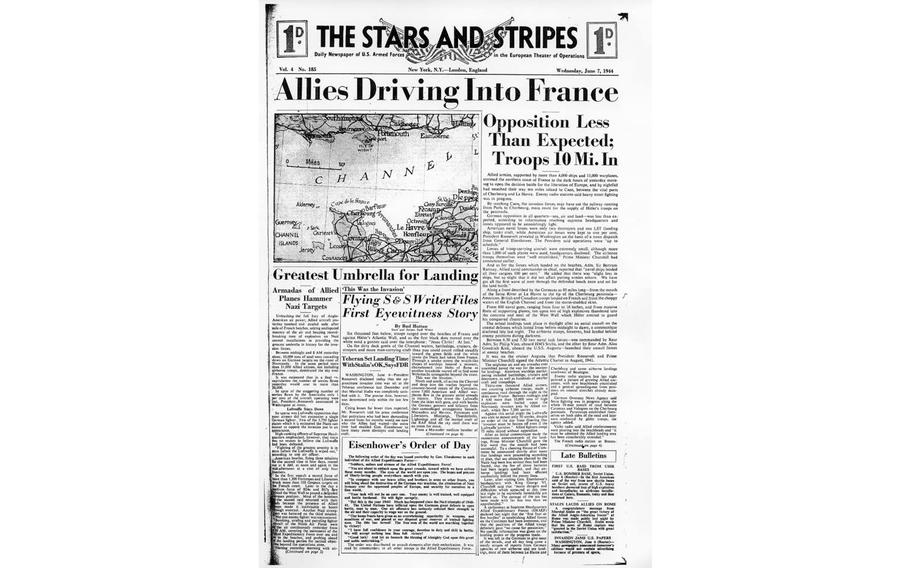

The Stars and Stripes front page for June 7, 1944. (Stars and Stripes)

EDITOR'S NOTE: Robert L. Moora was managing editor of the Stars and Stripes in London on June 6, 1944. After the war he worked on the New York Herald-Tribune until 1957 when he joined the press relations staff of Radio Corporation of America.

ABOUT 7:30 the morning of June 6, 1944, the telephone awakened me in the London flat I shared with a New York Herald Tribune war correspondent. I had been at work until well after 2 a.m., so the cobwebs of sleep were thick as I answered the phone.

"I tried to get you at the office," said the caller. I recognized the voice of Bud Hutton, chief Air Force correspondent for The Stars and Stripes, who had gone to a B-26 base a few days earlier.

"The office!" I exclaimed. "At this hour? Are you nuts?"

"No, I thought sure you'd be there," Bud said. "You're going right down, aren't you."

The cobwebs began to clear.

"Yes," I said. "Have you got a good story?"

"Damned good, but I'll have to call it in to you later," Hutton said and hung up.

I crossed the room and shook my sleeping roommate.

"Get up!" I told him. "The invasion is on."

No better evidence could be offered of the tight security that surrounded the planning and execution of the Normandy landings. Even I — managing editor of the Army's own newspaper, who had a crew of reporters assigned to cover the invasion — did not know when and where it was to take place.

That was the beginning of a momentous day in the career of Stars and Stripes. Except for the surrender itself, it was the biggest story of the war.

As the Trib correspondent and I dressed hastily to get to the British Ministry of Information — and listened in vain to the radio for the invasion announcement, which did not come until 9 a.m. — some other Stripes personnel were in more precarious positions.

G. K. Hodenfield (now education editor for the Associated Press in Washington) was pinned down by heavy enemy fire atop the cliffs of Omaha Beach, which he had scaled by ladder with a Ranger battalion. We were not to hear from Hod for six days, so furious was the fighting in that sector.

What happened to Hod was another good example of the security that surrounded Operation Overlord. Like all other correspondents who had been accredited to cover the actual landings, he had been whisked out of London time after time over a period of months to cover "maneuvers," the nature of which could not be revealed by the reporters even to their managing editors.

One day he received another routine summons to be at a certain place on the south coast of England. Several times he had accompanied the Rangers on practice landings along the coast. He arrived at the appointed place on time, wearing field attire except for a brand new officer's shirt which had cost him $12. (Hodenfield was one of the few lieutenant reporters on Stripes' staff). There had been a party in London the night before, and he was not feeling in top condition as he boarded the landing craft.

"Well, where are we going this time?" he asked the colonel in command, as the vessel eased out into the English Channel.

"You haven't been briefed?" the colonel asked in surprise. Hod said he hadn't.

The colonel produced a map, pointed to a specific location and said, "We go in here at H-minus-40 minutes."

Hodenfield studied the map, then said, "Colonel, I know the south coast of England, but I can't figure it out. Where is the landing in relation to, say, Plymouth or Bournemouth?"

The colonel eyed him curiously.

"Hod," he said, "that's not the coast of England."

Hodenfield added:

"The most horrible fate any newspaperman can contemplate is to be on the biggest story of his life, with no possible way to get the story back to his paper.

"I was one of the first war correspondents ashore on D-Day. A world press pool was in effect, and my story back to The Stars and Stripes in London would be made available to everyone — the Associated Press, United Press, International News Service, Reuters, the works.

"The plan called for the Rangers to break out of Pointe d'Hoc before noon on D-Day and link up with the 29th Div coming down the road from Omaha Beach on our left.

"Then it would be a fairly simple matter — I hoped — for me to find 1st Army Press Camp and file my stories.

"But it didn't work out that way. The Rangers didn't get off Pointe d'Hoc for three days. Pretty damn lucky to get off at all, as far as that goes.

"Then, late in the afternoon of the second day, a landing craft hit the beach with some supplies from a ship lying off-shore. I think it was the battleship Texas.

"Sitting in a shell hole, I scribbled a story with pencil on crumpled note paper. I gave it to one of the crewmen, and he assured me it would be sent off from the ship.

(It never showed up. And just last fall I learned what must have happened to it.)

"The crewman gave it to an officer. The officer gave it to a Marine combat correspondent. The Marine radioed it to Marine Hq in Washington. Marine Hq filed it away.

"A newspaper friend who covers military affairs found it in those files by accident one day.

"Some day I'll have to go look at it."

While Hod lay pinned down atop the Omaha bluffs, Bud Hutton was again in the air in a B26, part of the massive aerial support being given soldiers who landed on the Normandy beaches on D-Day.

Bud's B-26 delivered its load of bombs from medium altitude and, when it returned, Bud attacked the typewriter to produce the only story that S&S got the first day from any of its reporters in combat.

Here, again, was an example of tight security, Hutton and I, as veteran newspapermen and, at the start, co-managing editors of The Stars and Stripes, were close friends; but Hutton, briefed along with other airmen on the timing of the landings, refused to tip me off until the attack was well under way and he could make the guarded phone call at 7:30 a.m.

Another Stripes reporter, Philip H. Bucknell, lay with a broken leg in a field in Ste. Mere Eglise, where he had dropped by parachute with the 82nd Airborne Division. We were not to hear from him for nearly a week.

For five days Buck lay in the field or in a makeshift hospital before the 82nd could fly him back to England. When he arrived at the hospital there, Buck insisted on writing a story before they placed him on the operating table to set his leg. The medic captain in charge, impressed with the S&S correspondent's dedication to his job, dispatched a sergeant to London to deliver the copy. (Buck, I am sorry to report, died last year at his Rockleigh, N.J., farm after a long illness. He had served as news chief of the S&S New York bureau for at least 10 years after the war.)

What happened to Bucknell was still further evidence of the tight security before D-Day. Assigned to drop with the 506th Regt of the 82nd, he had been briefed on the plans for invasion. They were to take off about midnight and drop about 1 a.m., five hours before the landings by sea.

The planes were warming up — just as they had done many times before for practice missions — when Buck walked into the officers' club for a nightcap of sherry. (He was only a corporal but Stripes correspondents generally were given the privileges of civilian correspondents, a necessary factor in their jobs.)

When he finished the drink, he turned toward the door. The bartender, a noncom, pointed to the bottle which he had replaced beneath the bar. (Even sherry was scarce in those days.)

"Are you coming back?" he asked.

Buck stared at him in amazement.

"What do you mean?" he blurted.

"If you're coming back," the barman said, "I'll save you one."

Buck hesitated a moment, then answered in a tone that somehow carried determination, "Yes, I'm coming back." Then he walked out to whatever fate the night held in store.

Security? Even the bartender in the officers' club, privy to all conversation among his customers, did not know that this was it.

Back in London, the Stars and Stripes office on June 6 was a bedlam. Although it received immediate copy from only one of its reporters engaged in the landings, it had literally a thousand times more material on the assault than it had space for.

There were scores of background stories prepared in advance by all branches of the service, U.S., British and Canadian, and processed through the British Ministry of Information. There was a flood of copy written by wire service and pool reporters, some radioed from the Navy ships during the engagement, some from the beachhead itself, and all of it made available to all news media.

In mid-morning, I consulted with Lt. Col. Ensley M. Llewellyn, then officer-in-charge of Stripes.

"Colonel," I said, "let's go to eight pages today and drop back to four next Monday." (Because of the newsprint shortage in Britain, we were limited to a four-page daily, with the exception of one eight-pager each Monday.)

"Can't do it," he replied. "The newsprint pool won't supply the paper."

"In that case," I went on, "we'll skip the comics, limit sports to the baseball scores only, cut the Russian front and Pacific stories to a minimum, and devote every possible bit of space to the invasion."

Then the staff went to work, writing, editing, boiling down and otherwise preparing the copy for next morning's paper. As managing editor — selfishly, perhaps, but having held the helm of the paper for two years — I took the prerogative of writing the lead story, the account of the landings.

At 10 p.m. the presses started to roll, a triumphant banner headline reading: "Allies Driving into France."