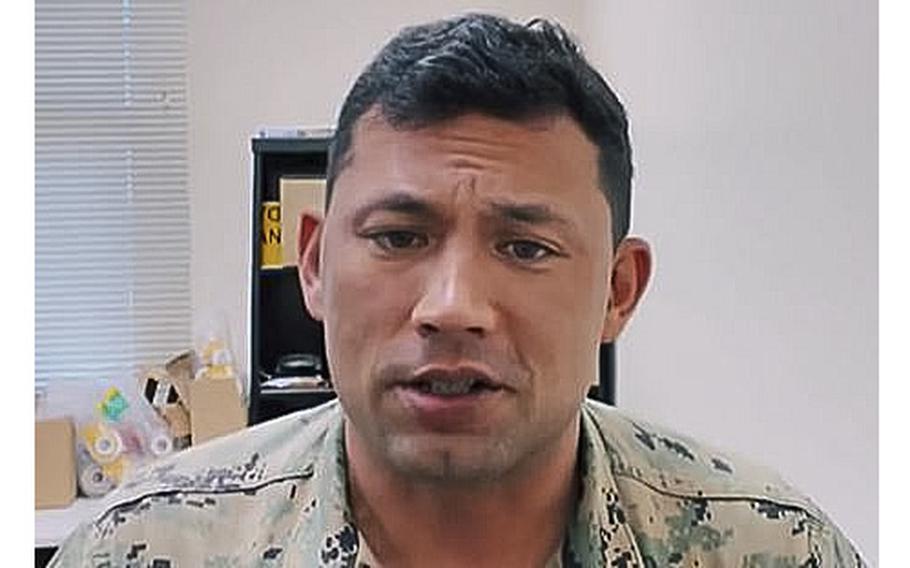

A video screen grab shows Gunnery Sgt. Ian Futrell, a Marine stationed at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, S.C., who is being charged with felony child abuse. (TikTok)

BEAUFORT, S.C. (Tribune News Service) — Red marks and bruises scattered across his face and body, the 6-year-old boy couldn’t tell Port Royal police what happened. Adopted from Hungary just two months prior, Ollie spoke fluent Hungarian but knew little English.

With the help of Google Translate, ER doctors at Beaufort Memorial Hospital asked Ollie how he was hurt. “Papa went boom boom,” the boy replied, according to his mother, making a pushing motion and pointing to a picture of the stairs in his home.

Ollie’s adoptive father, Ian Futrell, 38, of Beaufort, was arrested on charges of felony child abuse on June 9, 2022. From Ollie’s injuries and translated testimony, police accused Futrell of choking the boy, pushing him down the stairs and throwing him into the side of a metal dog kennel.

Futrell, a Marine, was indicted by a grand jury on Nov. 11 and pleaded not guilty at his arraignment hearing, according to Capt. John Griffith of the Port Royal Police Department.

Futrell currently serves at the Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) in Beaufort as a gunnery sergeant, an officer rank specialized in firepower and unit training. He arrived at the Beaufort station in January 2020, and has held his leadership position since 2019.

As a history of alleged abuse comes to light, MCAS officials are prepping a board to decide whether Futrell will be removed from the Marine Corps. Planned for the end of April on Parris Island, the hearing will address allegations of Futrell’s child abuse, steroid abuse and extramarital sexual conduct, according to emails sent from the Marines’ legal team.

The April proceedings are merely administrative and will not determine Futrell’s guilt or innocence. A criminal trial for the nearly year-old charges has not yet been scheduled, according to Jeff Kidd, a spokesperson for the 14th Circuit Solicitor’s Office.

Still, Suzanne Turner, Futrell’s ex-wife and Ollie’s adoptive mother, says her son’s story has been “swept under the rug” by the Marine Corps. Even after being informed of Futrell’s history of reported abuse — including allegations from another ex-wife — leaders at the Beaufort station silenced her requests for accountability and stood behind her ex-husband, she told the Island Packet and Beaufort Gazette.

“When it became clear to the (Commanding Officer) that I was not backing down ... he cut off all communication with me,” Turner said. She then received an email from another official telling her to “let the civilian courts handle it.”

Turner and her attorney are advocating for Futrell’s removal from the Marine Corps under the “other than honorable” label, an administrative discharge that disqualifies service members from veteran’s benefits and prevents them from reenlisting.

“How is the Marine Corps standing by his side? How is he not receiving consequences for what he did?” said Turner, the proud daughter of a retired U.S. Army veteran. “It’s deplorable.”

Futrell has garnered over 45,000 followers on TikTok, where he shares short videos about the Marines and military life. His followers know him as “Gunny.”

MCAS GySgt. Robert Dea said the station is aware of the accusations and “takes all allegations of misconduct very seriously,” but would not comment further on details of the hearing.

Christopher J. Geier, Futrell’s defense attorney, declined to comment on the case.

‘It was like something snapped’

Turner and Futrell adopted Ollie and his younger brother, Kazmer, in April 2022, just two months before Futrell was arrested. Like many other international adoptions, the process wasn’t easy, lasting 20 months and costing nearly $60,000, Turner said.

In the weeks leading up to the incident, Turner says her ex-husband seemed like “dad of the year” — carrying the boys on his shoulders, buying them toys, and teaching them how to ride a bike.

But those behaviors soon came to a sudden stop, she said.

“It was like something snapped,” Turner said. “He just kind of withdrew. He wasn’t really helpful with the boys anymore. He was losing patience with them.”

Turner added that Ollie is a special needs child, having been diagnosed with a handful of neuropsychiatric disorders prior to his adoption. Before doctors in Charleston found the right mix of medication, Ollie was prone to emotional outbursts.

“These were things that we knew we were getting into,” Turner said of her son’s diagnoses. Ollie was also “badly abused” during his time in Hungary’s foster care system, which contributed to his condition, she said.

One of Ollie’s outbursts came on June 9, 2022. Futrell was watching the boys at the couple’s Beaufort home while Turner was away at an appointment, she said.

Heading back home, Turner received a text from her husband, saying he could not deal with Ollie. According to the police report, when she arrived and asked her husband what happened, Futrell responded, “Ollie was crying and wouldn’t listen, so I smacked the [expletive] out of him.”

That’s when Turner noticed Ollie’s injuries. Immediately afraid for her sons’ safety, she took them upstairs and locked the door behind them, taking pictures of Ollie’s marks and bruises for documentation, she said.

“I told the boys, ‘It’s a race: Who can get their shoes on and get to my car the fastest?’” Turner said. Standing between Futrell and her sons, she led them out of the house and drove straight to Beaufort Memorial Hospital.

The June 2022 incident only revealed further allegations against Futrell, Turner said. While in the hospital, she connected with another one of his ex-wives, with whom Futrell lived in North Carolina until their divorce in 2018. After hearing Turner’s story, the woman shared her own. According to court documents, the woman alleged that Futrell had slapped and grabbed the throat of their daughter, who was only 13 at the time of the couple’s divorce.

The interaction spurred that woman to take action, using the allegations to win sole custody of her children in a North Carolina court. According to court documents, the woman claimed her two children were fearful of Futrell — who often had “fits of rage” in the home — and had to see a therapist to cope with their visitation time with their father.

Ollie also attends trauma therapy, Turner said, helping him to cope with a history of abuse that spanned multiple years and two countries. He and his younger brother are in kindergarten at a Port Royal charter school, where both boys are “thriving,” she says.

Turner now has full custody of the boys, and the three of them recently moved to Port Royal. It’s an older house, Turner admits, but she’s grateful the boys have a safe home.

“They view (Futrell) as the Boogeyman,” she said. “They’re afraid of him. They don’t want him around.”

But Turner still encourages the boys to talk about what happened — and they do. She recounted a common back-and-forth she has with her son: After she tells him “I’m sorry that happened,” Ollie will respond, “It’s okay, it’s not your fault.”

A culture of violence

As a fifth-grade teacher at Bolden Elementary Middle School, located on base, Turner says she witnesses firsthand the pervasive presence of child mistreatment in the Marine Corps.

“Child abuse is so prevalent in our schools,” she said of the Department of Defense’s education system. “Drill instructors are sometimes very abusive to their children because they’re in that mindset of being a drill instructor all day ... that mindset of, ‘You have to act right or you get killed.’”

Experts agree that military families may be especially vulnerable to child maltreatment, tying increased domestic violence to stressors like deployment and unstable living situations.

At the beginning of every school year, Turner’s classroom is visited by a representative from the Family Advocacy Program (FAP) — which handles child abuse and domestic violence in the military — for a talk about the warning signs of mistreatment.

“It’s sometimes very obvious,” Turner said. “Some parents you just don’t contact. Their kids are acting out at school, but if you let the parents know, the next day they’ll come to school with bruises. It’s a fine line to walk, and it’s definitely changed the way I view today’s military.”

(c)2023 The Island Packet (Hilton Head, S.C.)

Visit The Island Packet at www.islandpacket.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.