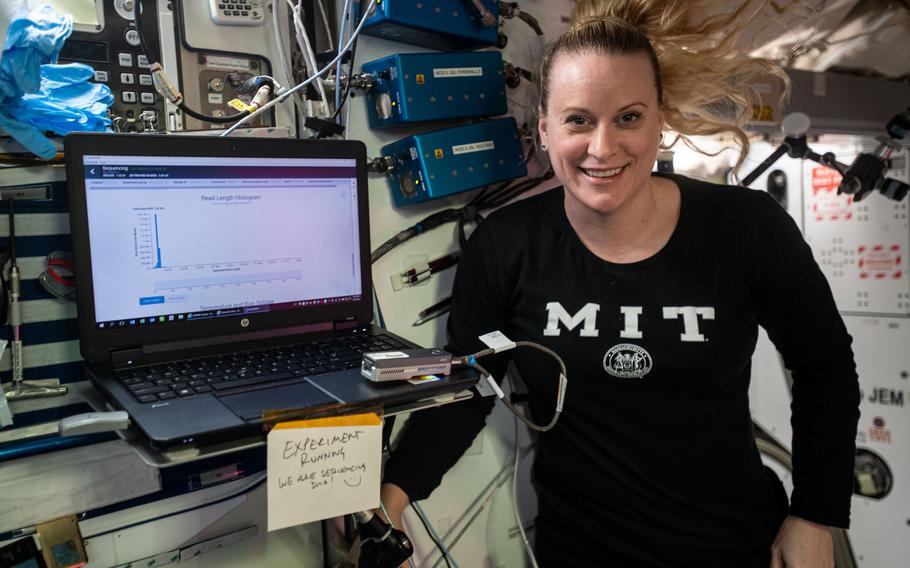

NASA astronaut and Expedition 64 flight engineer Kate Rubins is pictured during DNA sequencing activities aboard the International Space Station, Jan. 22, 2021, for an experiment that seeks to diagnose medical conditions and identify microbes. Just months after completing her second space mission, Rubins has been commissioned in the U.S. Army Reserve. (NASA)

She has earned two doctorates, researched some of the world’s deadliest viruses in Africa and spent 300 days in space — and now Kate Rubins is a soldier.

Rubins, 43, who returned from her latest six-month trip aboard the International Space Station in April, was commissioned as a major in the Army Reserve during a ceremony last week.

She will serve with the 75th Innovation Command, a unit designed to help the Army make inroads into the private sector for research and development. It supports the Army Futures Command’s efforts to modernize the service for strategic competition with China and Russia.

“Now, more than ever, we need top-notch scientists, clinicians and microbiologists like Dr. Rubins paving the way for the future of the Army and our great nation,” Col. Amy Roy, deputy commander of U.S. Army Medical Recruiting Brigade, said during a commissioning ceremony Nov. 2 in Houston.

The astronaut and scientist will bring a “wealth of education, skills and experience” to the service’s medical corps, said Lt. Gen. Jody J. Daniels, commanding general of U.S. Army Reserve Command.

She cited Rubins’ degrees, fellowships and “on-scene medical experience combatting viral outbreaks in central and west Africa,” in addition to being among the top four female astronauts in terms of time in space.

Expedition 64 NASA astronaut Kate Rubins is helped out of a Soyuz MS-17 spacecraft just minutes after she, and two Russian cosmonauts, landed in a remote area near the town of Zhezkazgan, Kazakhstan, April 17, 2021. Just months after completing her second space mission, Rubins has been commissioned in the U.S. Army Reserve. (Bill Ingalls/NASA)

“You definitely travel quite a bit … in different dimensions,” Daniels said, before swearing Rubins into the service.

Born in Connecticut and raised in Napa, Calif., Rubins knew from the time she was 5 that she wanted to be an astronaut, geologist and biologist, Roy said.

“So far, she’s achieved two out of those three goals,” Roy said. “You know, just the easy goals.”

In a NASA interview just before she was selected as one of nine members of space agency’s 20th astronaut class in July 2009, she said she’d initially thought she would have to be a fighter pilot before getting a chance to go to space. But she became fascinated with molecular biology and viruses while working on public health prevention of HIV in high school and spent 15 years pursuing that interest.

While an undergraduate at the University of California, San Diego, she conducted HIV research at the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences, which was founded by polio vaccine developer Dr. Jonas Salk. She earned a doctorate in cancer biology from Stanford University Medical School in 2005.

Rubins studied smallpox and the Ebola virus at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, she said in the 2009 NASA interview. On her first mission to the ISS in 2016, she became the first person to sequence DNA in space and grew heart cells in a cell culture as part of the Cardinal Heart experiment.

On her last mission to the ISS, she realized she wanted to give back to the U.S., she said last week. She’d also seen “what it does to people to live under an oppressive regime” during her time in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kazakhstan and Russia, she said.

Rubins decided to join the Army Reserve in part because of her time working at Fort Detrick, Md., from 2000 to 2009, she said.

The cutting-edge research at that facility was promising not just for therapeutic treatments and vaccines against bioweapons, but for civilian applications, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, she said.

Rubins was also inspired and encouraged by her stepfather, who had served as an Army Reserve chaplain for 10 years.

“I really admire him and I admire many of the people that are here today,” she said. “A lot of my heroes are in the Army and they embody values that I would like to strive to become.”

Daniels, head of the U.S. Army Reserve Command, said that no matter what goals someone might have in their civilian career, there’s a place for them in the Army Reserve.

“It seemed like a really excellent fit” with her career as an astronaut, Rubins said. “I’m looking forward to both of these careers together.”