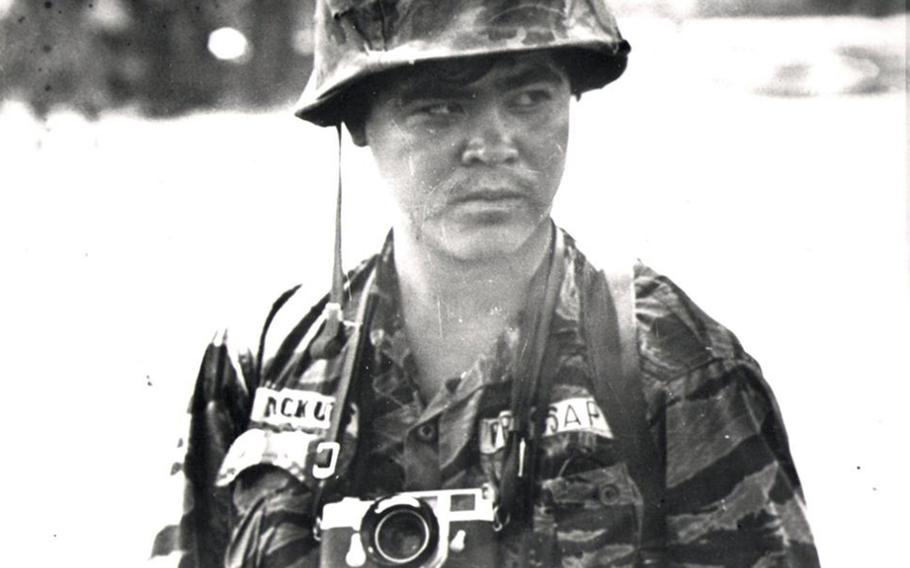

This undated photo shows Associated Press photojournalist Nick Ut in South Vietnam. (AP)

Vietnam-era war correspondents wore uniforms, ate field rations and shared many of the deprivations and dangers of ordinary fighting men.

Five decades later, their ranks are thinning but those who remain are still telling stories about “the last good war” for combat journalists.

When Robert Hodierne arrived in Vietnam as a 21-year-old freelancer in spring 1966 he was considered the youngest accredited foreign correspondent in the country.

“I’d never had a photograph published,” he recalled in a phone interview. “The fact that somebody like me could get credentials and make a living as a foreign correspondent says something about how open and loose things were for journalists over there.”

Accredited journalists in Vietnam interacted freely with troops and filed uncensored reports about the conflict. The open door for the press was a hallmark of the war.

“It is the only war the U.S. has been involved in where reporters weren’t subject to censorship, and it was the last good war for reporters,” Hodierne said.

In those days it was simple for journalists to hitch rides on U.S. military aircraft and link up with frontline units.

“As a correspondent you could go out and wave down a chopper or a plane and get on and go anywhere you wanted,” said Jim Shaw, a civilian, who sought out an assignment overseeing 10 staff at Stars and Stripes’ Saigon bureau in 1966.

Hodierne saw combat with every major American unit in Vietnam, “from the DMZ to the Delta,” he said.

“The grunts had the same dark humor as me,” he said. “I admired greatly their ability to endure. I’ve had a made a career making sure Americans understand what these young men and women go through when we send them to war.”

Fitting inLife for a journalist working in Vietnam was surreal at times.

On a typical day, Hodierne said, he might have woken up in his apartment in Saigon, downed some coffee and a bagel, headed over to the airport to hitch a flight to the jungle, linked up with a unit, observed a fight, and ridden a chopper back to Saigon.

Reporters couldn’t file directly from the battlefield as they can today. In Vietnam they phoned in accounts from the nearest U.S. base or returned to Saigon to file.

“A challenge was getting back to Saigon as fast as possible,” Hodierne said. “You had to hand-carry your film or give it to a pilot and sometimes it made it and sometimes it didn’t. Keeping film dry once it was out of the camera was another challenge.”

Hodierne was so impressed with the troops he met in Vietnam that he went back to the States, joined the Army and found himself back at the war as a Stars and Stripes reporter in 1969.

In an age before social media and the internet, telephone calls to the U.S. were rare and expensive. Most communication with headquarters was done by telex – a machine that sent and received printed text messages.

“In Vietnam you felt a long way from home,” said Pulitzer Prize-winner Peter Arnett, who had a 13-year stint with the Associated Press in Vietnam, starting in 1962.

The Stars and Stripes staff, even civilians, wore uniforms in Vietnam, although it wasn’t required, Shaw said.

Other journalists bought uniforms on the black market, Arnett recalled. “We looked pretty much like ordinary soldiers when we covered them,” he said.

Reporters would spend days or weeks in the company of infantry units, chatting freely with the men and the officers.

“We could write anything we wanted to,” he said. “However, clippings of our stories, published in American newspapers and Stars and Stripes, would be sent back to the grunts by their relatives and the soldiers would know what we were saying about the war within a few weeks. Because we relied on returning often to the same exceptional military outfits we would understandably be careful in being accurate in our observations,” Arnett said.

At times there was tension between the talented young military journalists -- some of whom were sent to Stars and Stripes directly from deployed units -- and the brass, Hodierne recalled.

He said he was threatened with court-martial when he wrote a story about 23rd “Americal” Infantry Division soldiers who refused to fight.

A piece about a Special Forces camp that was almost overrun also got some blowback, he said.

“The public affairs officers maintained that it wasn’t under siege but I was there in the TOC (Tactical Operations Center) so I know what was going on,” he said, recalling that artillery was called in on every grid square around the camp to fend off the attack.

Casualties and resentmentAs U.S. troop numbers increased, the American public’s hunger for news about the war grew and hundreds of journalists were dispatched to cover the fighting.

Nick Turner, who worked for the Reuters news agency in Saigon for three years from 1962 and stayed on as a freelancer until 1971, said he didn’t know much about Vietnam before he got there.

“There weren’t many books about it and there was no Google in 1962,” he said.

Turner’s work took him to Vietnam’s neighbors in Southeast Asia, which were also struggling to contain Communist insurgencies sponsored by the Soviet Union and Red China. It was feared that, if Vietnam fell, other capitalist regimes in the region would topple like dominoes.

The tipping point came in 1965, when Indonesia – the largest domino in the “domino theory” -- thwarted an attempted Communist takeover. That same year U.S. forces fought the North Vietnamese to a stalemate at Plei Me and Ia Drang, which was essentially a victory for the Americans, he said.

“The Americans had achieved their goal of halting the Communist advance in Southeast Asia,” he said. “They had achieved what they wanted to in Vietnam but stayed too long.”

During a tour of the Laotian border Turner asked the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, Gen. William Westmoreland, why he didn’t emulate Britain’s successful tactics in Malaysia, where a Communist insurgency was beaten by small units living among the local population.

“The Americans did everything with helicopters and planes and artillery and flew ice cream to troops in the field,” Turner recalled. “When a company in the field ran into trouble the heavy stuff was called in. It caused a lot of casualties and resentment among the Vietnamese people.”

Westmoreland maintained that his hand was being forced by politicians responding to the parents of drafted soldiers, Turner said.

‘Great fraternity’Public attention to Vietnam grew to a fever pitch as the conflict and casualties expanded in the late 1960s. U.S. newspapers and broadcasters invested heavily in their war coverage making stories from the battlefield a daily fixture.

Some of stories and images from Vietnam have left indelible impressions on the American psyche.

Who could forget Malcolm Browne’s Pulitzer-winning photograph of a monk’s self-immolation in a Saigon street in 1963; Nick Ut’s 1972 image of a girl burned by napalm for the Associated Press; or Eddie Adams’ photo of a police chief executing a Viet Cong prisoner.

Some of the journalists in Vietnam became household names, such as Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck, who worked there for Newsday in 1968.

Gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson also made an appearance in Saigon in April 1975, six days before the South Vietnamese capital fell to the communists. Thompson was on assignment for fledgling Rolling Stone magazine but seemed out of his depth in a city on the verge of collapse, Arnett said. He went home a few days after he arrived.

The Vietnam correspondents followed in the footsteps of journalists who covered World War II and the Korean War, he said.

“We were part of a great fraternity that I haven’t seen since,” Arnett said.

Today’s limitationsOpen press coverage of the war in Vietnam was seen by the authorities as politically necessary to retain public support for the draft. Today’s all-volunteer military means that support is less important -- meaning less access to the battlefield for reporters, Arnett said.

“The casual intimacy of the Vietnam years between reporters and soldiers has been replaced by a wary tolerance of the media,” he said. “Only a handful of embedded journalists are in residence with units at any one time because news organizations are not getting the kind of stories that are of real value to readers and viewers.”

Some blamed the press for failure in Vietnam.

CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite, who visited Vietnam in 1968 and, shocked by the devastation wrought by the North’s Tet offensive, declared the war “mired in stalemate,” is often credited with turning the American people against the war.

The reporters who covered Vietnam were focused on important stories such as troops engaged in combat or faulty weapons. There were plenty of stories about battlefield successes and bravery, but editors weren’t interested in gossip in those days, Arnett said.

“A general making out with a Red Cross girl isn’t a story, but a commander reporting that his men refuse to fight is news,” he said.

Experience in Iraq and Afghanistan give Arnett a good perspective on how war reporting has changed over the years.

“The requirement remains that the writer and photographer get as close to the action as possible. The eyewitness accounts of action remain the most consequential reporting of wars. What does change from era to era is the significance of the conflict the reporter is covering, and the appetite of the market for dangerous coverage," he said.

Lasting impressionsThe war has stayed with the Vietnam-era correspondents. Arnett has written several books about the conflict. His contract with CNN was not renewed after he worked on a controversial story about Operation Tailwind in Vietnam in 1970.

It aired in 1998. He was later dismissed from NBC after giving an interview to state-run Iraqi TV in 2003.

Turner is working on his own book. Hodierne keeps in touch with Vietnam veterans and attends unit reunions from time to time.

A photograph that Hodierne took on patrol shows Army Staff. Sgt. Joe Musial, pinned down by enemy fire next to dead and wounded comrades.

“His nickname was Sgt. Rock,” he recalled. “He did three tours in Vietnam and was awarded two Silver Stars and three Bronze Stars” and three Purple Hearts.

Hodierne contacted Musial after the war and pieced together his life story from interviews with troops he’d served with in Vietnam.

“He was a garrison screw-up,” he said. “He would get in fights and get drunk and get busted down (in rank), but let him loose on the battlefield and he was hell on wheels. These kind of guys don’t survive in peacetime very well.”

He wrote about meeting up with Musial, then 65 and suffering from lung cancer.

After the war, Musial went to work on oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico and lost a leg in an accident there. He used the settlement and his Army pension to buy a house in rural southwest Michigan.

The story, written for Reader’s Digest in 2002, closes with this line:

“... The call came on a chilly afternoon. Joe Musial, Sgt. Rock, died in the early morning hours of Nov. 11, 2001. Veterans Day.”

These days Hodierne is still in touch with other Vietnam veterans.

“Probably there is not a week that goes by where I get some random contact from a Vietnam veteran who has seen my stuff on the web,” he said.

Arnett said he hadn’t had psychological issues as a result of his war experiences and attributes that to his “robust” upbringing and strong belief in his mission. However, his most enduring memories of the war are of colleagues killed in action there. Photographers Henri Huet and Larry Burrows died when their helicopter was shot down over Laos in 1971.

Reporters Bernard Fall was killed by a landmine in 1967, and John Cantwell was shot in a Viet Cong ambush in 1968.

More than 60 journalists working for Western media were killed in action during the war.

“They were doing everything to achieve the kind of professional goals and success that they thought were worthwhile to get the information back home about what was going on. Their examples of courage and commitment to journalism have inspired me over the years,” Arnett said.

robson.seth@stripes.com Twitter: @sethrobson1