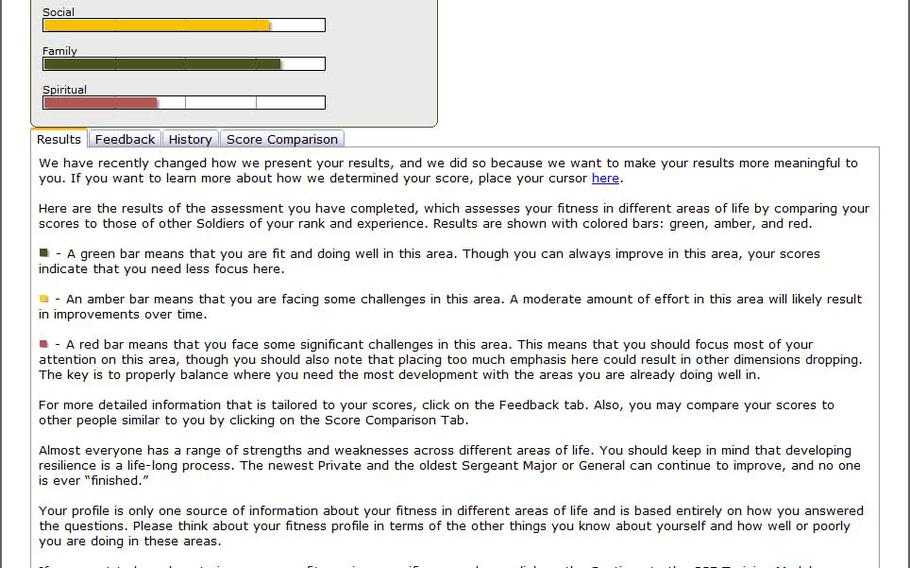

The results of Army Capt. Ryan Jean's recent Comprehensive Soldier Fitness test show a lesser score under the "Spiritual" category. Jean, an atheist, believes the test is biased against those who reject religion. (Courtesy of Ryan Jean)

WASHINGTON — In early August, a small group of soldiers, airmen and their spouses gathered at a Panera Bread restaurant near Fort Meade, Md., to talk about the meaning of faith and how to share their convictions about life’s deepest questions.

As they sipped coffee and nibbled pastries, the scene might have passed for a low-key Wednesday night Bible study except for one thing — the members of the newly formed ATOM, or Atheists of Meade group, didn’t have any Bibles. Their belief system, they say, stops at the boundaries of the natural world.

It’s this rejection of supernatural belief that pushes the group off base instead of having the dedicated meeting space that religious groups get, said Army Capt. Ryan Jean, one of group’s organizers. That’s not fair, he said, because ATOM mostly does what religions do — provide fellowship and a chance for ethical and moral development.

“If there’s a reason to support religion in the military, it’s the ethics and values that come out of it, not the supernatural claims,” he said. “We also have constructive ethics and values, but we rally around humanism rather than the supernatural.”

Worldwide movement

As DOD’s "don’t ask, don’t tell" policy enters its final weeks, another mostly closeted military group is stepping into the open this summer.

ATOM and nearly 20 other unofficial atheist fellowship groups have sprung up in recent months on U.S. military installations in the United States and around the world. In addition, students at all three service academies have started officially recognized groups of nonbelievers at their institutions. It’s all part of a coordinated effort to bring atheists out of the shadows push for the Department of Defense to give groups that explicitly reject religion the status and First Amendment protections that religious groups have.

It is a controversial — some call it self-contradictory — strategy that the movement’s organizers say is necessary to overcome a longstanding structural bias in the military against people who follow no religion.

The military atheist movement took off, many participants say, in the wake of controversy over “Rock the Fort,” a religious rock concert at Fort Bragg, N.C., in 2010. Atheists on the post, led by Sgt. Justin Griffith, formed Military Atheists and Secular Humanists, or MASH, and protested taxpayer funds supporting Christian proselytizing. MASH’s response, the atheism-themed “Rock Beyond Belief” concert, was canceled after base officials said it couldn’t be held in the same spacious facilities Rock the Fort had used. They relented after continuing accusations of bias, and the concert is scheduled for March 2012.

If successful, ATOM and groups like it would get access to on-base religious facilities. Jean would become what the Army calls a “distinctive faith group leader” — a volunteer lay religious leader who, according to regulations, “may provide ministry on an exception to policy basis when military chaplains are not available to meet the faith group coverage requirements of soldiers and their families.”

The ultimate goal would be the appointment of atheists as military chaplains in each service. Supporters say it will help ensure atheists’ fellowship needs are met, and their religious freedoms — including freedom from the imposition of religion — are protected. The wife of an airman stationed at Incirlik Air Base, Turkey, said the insularity of being stationed overseas heightens both religious involvement and the a sense of isolation for non-religious people

“We live in a Muslim country ... and a lot of things on the base revolve around the chapel,” said Athena Holter-Mehren, organizer of an atheist group on the base. “We’re asking for the same right to meet and be supported in our beliefs. I want to be part of a community where I don’t have to constantly justify myself and my beliefs to people.”

Demanding representation

The Washington, D.C., strategist behind the worldwide campaign says the concept isn’t so strange if you consider that chaplains do more than facilitate religious observance. They have a wide range of secular duties as well that brings them into contact with all servicemembers.

“It doesn’t matter what we believe, we can’t get away from them,” said Jason Torpy, a former Army officer and head of the Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers, or MAAF. “They’re on the command staff, and they’re already advocating for us in areas like mental health, family services and suicide prevention.”

Though it’s not the case with all chaplains, Torpy said, many view atheists as people to be converted or dismissed.

“Sure I can go talk to the chaplain, but there’s a good chance he’s going to disparage me a couple times and try to bring me to his views,” he said.

Because of the ubiquity of chaplains, Torpy said, the nearly 10,000 troops who according to DOD statistics identify themselves as atheists or agnostics need secular chaplains and lay leaders. It’s the only way to ensure that nonbelievers’ perspectives are understood and respected in a military heavily influenced by Christian piety and social conservatism, he said.

“It’s not acceptable for chaplains to be ignorant about or hostile to a large segment of the community,” he said.

Chaplains react

Chaplaincy officials said they’re far from hostile to atheists, but they are befuddled by MAAF’s campaign.

“Most military people I know scratch their heads when they hear about atheist chaplains,” said Army Lt. Col. Carlton Birch, a chaplain and spokesman for the Army chief of chaplains office. “Regardless of all the things chaplains do — counseling, family programs, morale building, etc. — at the heart of every chaplain’s mission is the free exercise of religion. I’m not sure how atheists plan to sincerely subscribe to the Army chaplain motto, ‘Pro Deo et Patria’ — for God and country.”

Air Force Chief of Chaplains Maj. Gen. Cecil Richardson suggested it’s a contradiction to treat atheism as religion. Nevertheless, Air Force chaplains are as ready to help atheists as anyone else, he said in written statement to Stars and Stripes.

“Because chaplains by their nature and calling see others through a lens of care and compassion, no chaplain would ever turn any Airman away,” he said. “There is no litmus test regarding faith or religious affiliation. Chaplains are eager to help anyone in need, including atheists. All are welcome and encouraged to seek assistance from chaplains concerning personal, family, spiritual or work issues.”

If atheists don’t want to interact with chaplains, there are ways to avoid them, Richardson said.

“The Chaplain Corps is faith-based, but it should be remembered that there are lots of non-faith-based helping agencies in the military,” he said, including family counseling and mental health services. “They are also available to atheists.”

Atheist doubts

Some atheists question the potential institution of nonbelieving chaplains.

In a webcast earlier this year, comedian, illusionist and outspoken atheist Penn Jillette confessed to ambivalence. While he instinctively supports atheists demanding their rights, he said, atheist chaplaincy might undermine the intellectual foundations of atheism and at the same time, demean sincerely religious military people.

“It feels slightly disingenuous,” Jillette concluded.

A military spouse who is a member of the Fort Meade atheists group also expressed reservations at a recent meeting about bringing ATOM under the wing of official U.S. military religious structures.

“I just wish there was some way to do this without becoming part of that,” said Katherine Moore.

“But what about the fact when you go to a chaplain for counseling, it’s protected by a higher level of confidentiality than just about anywhere else?” responded Air Force Technical Sgt. Doyle Stricker. “Chaplains do some important things. ... We need to be there so our needs get met.”

What military atheists stand to gain from chaplaincy outweigh the drawbacks, Moore agreed.

Standing up

Military atheists often have to be cautious, said Clint Rasic, a retired Air Force major working as a civil servant at Kaiserslautern Military Community in Germany.

During his active military career, Rasic said he learned to keep his beliefs quiet, especially when those above him in the chain of command were forward with their religiosity.

“I once had a commanding officer who always started his commander’s call with a prayer. And you can’t decline a commander’s call,” he said. “When you value your career and you know the person who is writing your performance reports has these beliefs, you’re very careful about showing who you are.”

He started a MAAF chapter at Kaiserlautern two months ago that is attracting about 12 attendees per session.

“I want to encourage young people coming in — you’re not a heathen, you’re not an outcast,” he said. “I hope they can be more open about their beliefs through their careers than I was.”

Ken LaBelle, an Air Force technical sergeant and Mandarin linguist stationed at Goodfellow Air Force Base, Texas, has been outspoken about his beliefs and taken heat for it.

After an on-base suicide, he told base leadership that although supporting the airman’s family was a worthy goal, mandating attendance at a chapel service to do so was a violation of the First Amendment.

“I got called into a lot of offices and yelled at by a lot of senior people after that,” he said.

LaBelle has started an atheist group affiliated with MAAF in late spring that is slowly growing in attendance.

“People are coming forward more about their beliefs today,” he said. “I don’t think the overall number of atheists has changed. But as we see more fundamentalist Christian actions like the “Rock the Fort” debacle, it motivates people to stand up.”

God's Army

A personal attack on his beliefs helped push Jean, who hopes to be named an Army distinctive faith group leader at Fort Meade group, toward a public role.

In 2009, Jean, then a junior captain in his mid-20s, was stationed at an Iraq-Kuwait border crossing when he was told to take the Army’s spiritual fitness test, part of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program.

The test enforces no sectarian slant, but does push soldiers to make certain metaphysical admissions, Jean said.

“To pass it I was supposed to say my existence has some cosmic spiritual significance,” he said. “I don’t believe that, and I failed the test.”

As he finished, the computer terminal flashed a message informing Jean he might be at risk for depression and feelings of worthlessness. Though the test results are supposed to be confidential, Jean was soon sent to see the local chaplain in charge, where he argued he shouldn’t have to lie about his beliefs.

The chaplain didn’t like hearing that, Jean said.

“That’s when he told me that yes, I was worthless, and that I have no reason to be in God’s army, and that I should resign my commission.”

Jean recently took the test again and received similar results, though he does not expect another confrontation with a chaplain.

“I know now what I did not know then (and what many still do not know) that while the test can be mandated the results are not required to be shared,” he said in an email. “As an officer, that gives me enough room that I feel comfortable standing up to anyone who might demand a copy of the results, but I doubt the same strength would be available to a lot of junior enlisted soldiers. As such, no, I won’t be going to a Chaplain about it, either, nor do I feel the need to seek help on it.”

Waiting for an answer

Earlier this month, Jean met with a chaplain at Fort Meade to discuss his lay leader aspirations. Despite profound religious differences, Jean said he walked away certain the chaplain would be willing work with the atheist group if Army officials sign off on appointing atheists to religious leadership positions.

Torpy, who is winding his way through DOD and individual service policies on the matter, said MAAF has submitted applications for lay leader status, but the requests are in limbo for bureaucratic reasons.

As those questions swirl round and round, the leaders of the chaplaincy have met him with stony silence, he said.

“They’ve had many opportunities to open their doors, but have chosen not to for whatever reason,” he said. “They’re lawyered up, but they’re not saying yes and not saying no.”

Continued silence or a negative answer on lay leaders could precipitate a new strategy, Torpy said.

Torpy, like many military atheists interviewed by Stars and Stripes, comes from a upbringing steeped in a Christian faith he later rejected. His phrasing, as he talked about the potential battle to come, echoed his God-fearing youth.

“In the fullness of time,” he said, if the military’s increasingly vocal minority of atheists doesn’t get a place at the table, MAAF and its allies might use legal means to try to force fundamental change on the chaplain corps, stripping it of nonreligious responsibilities and secularizing its mental health and social services functions.

It hasn’t come to that yet, Torpy said.

“Right now we’re just asking them to work with us.”