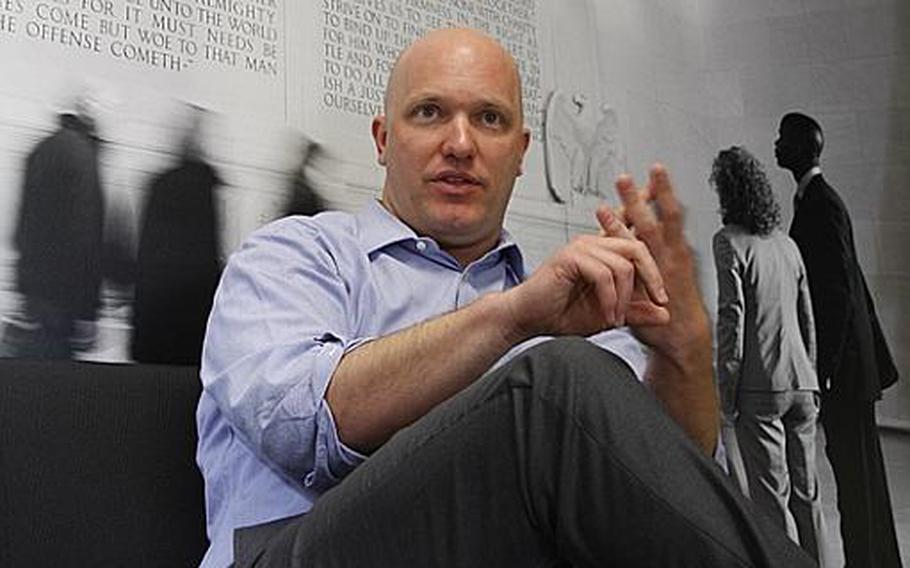

Paul Rieckhoff, executive director of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, relaxes in the New York office for the group. The 37-year-old helped found the group at the height of the Iraq war, concerned that voices of veterans were being ignored in national debates. (Leo Shane III/Stars and Stripes)

WASHINGTON — In 2006, at the height of the Iraq War, staffers at the advocacy group Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America practically had to beg reporters to cover their news conferences. Now, IAVA representatives are frequent cable news guests and regulars at hearings on Capitol Hill, where few if any veterans initiatives are passed without their blessing.

They’re advertising stars, thanks to donated public service spots and a partnership with Miller High Life. IAVA events drew crowds at the Super Bowl and this year’s presidential political conventions, among dozens of other high-profile events.

In just eight years, IAVA has transformed itself from an upstart veterans organization to a lobbying heavyweight and media favorite. For many Americans not connected to the military, they’ve become the face not just of the current combat generation but of all veterans.

That infuriates their critics, who see IAVA as a small, unrepresentative sample of returning war heroes, a veterans group with an uncharacteristic liberal bent and a business model that emphasizes online communities over traditional outreach.

They’re too loud. They take too much credit. They’re unwilling to wait for change. They’re too convinced that their unconventional strategies and overly aggressive approach are more helpful than what other advocates — and the Department of Veterans Affairs — are offering.

At the center of it all is the group’s founder, Army veteran Paul Rieckhoff, whose oversized personality and “mission first” mantra have become intertwined with IAVA’s rise and stumbles.

To many young veterans looking for a post-military career, he’s a role model. To critics weary of his grandstanding, he’s a villain.

He’s a veteran celebrity, and unapologetic about his personal style.

“When you’re out in front, you’re the one that’s going to take hits,” Rieckhoff said. “But that has been part of our strategy, to get our staff on TV and to keep the focus on our issues. We have a tendency to be a bull in a china shop. We think we have to be.”

Taking heat

Few see the brewing discontent directed at IAVA.

From the outside, the young advocacy group appears to work hand-in-hand on every issue with established veteran service organizations and government agencies. Officials from the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion, the Disabled Veterans of America and a host of other advocates say publicly that the group is an important new voice for all troops and veterans.

But in recent months, IAVA leadership has taken heat on several high profile issues.

Pentagon leaders openly grumbled when the group pushed for a nationwide parade to commemorate the end of the Iraq War, calling it false debate created by IAVA. They’ve drawn criticism for their public contempt for for-profit schools, with assertions that those institutions are destroying the value of the post-9/11 GI Bill.

And they’ve lost friends due to their strong criticism of VA Secretary Eric Shinseki, even as other veterans groups have publicly praised his efforts to turn around the department’s longtime struggles with claims backlogs and inadequate mental health care resources.

After a series of news articles critical of Shinseki — prompted by IAVA comments — Student Veterans of America, a young veterans group with close ties to IAVA, issued a statement defending Shinseki and stating that “the secretary is misunderstood by some of [our] peers in the veterans community.”

It was a mild but very unusual public rebuke for veterans lobbying organizations that rarely fight and typically collaborate on all major legislative and policy goals.

Officials from SVA said the comment was not a slap at IAVA. But privately, other veterans advocates celebrated the burgeoning fight, whispering that IAVA has grown too large, too fast without being credible representatives of the generation returning from war.

Online approach

IAVA officials aren’t surprised at the backlash but say the public perception of who they are is skewed, even by supporters.

They aren’t as large as many people think. The group has only a 40-person staff and $6 million in direct annual revenues. That’s less than what the 113-year-old Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States pulls in each month, and smaller than the $40-million-plus of the Wounded Warrior Project, a 10-year-old veterans advocacy group.

But IAVA officials boast that the organization also received almost $20 million in donated services and assistance in 2011 alone, which “allows us to punch above our weight class,” Rieckhoff said. Those donations include the group’s pricey Madison Avenue offices in New York City, as well as a series of television and print public service advertisements to promote IAVA programs.

IAVA claims 200,000 members but doesn’t charge any dues for membership or programming, so critics question just how many veterans they truly represent. The group conducted more than 350 events last year — dozens of baseball games, concert meet-ups and resume-building classes — but the bulk of the interactions come on the Community of Veterans site, an online bulletin board closed to everyone except verified veterans.

The 4-year-old chat site is IAVA’s crown jewel and also a frequent target of critics, who charge that it’s little more than a Facebook clone to boost membership figures.

“They aren’t bringing veterans together at a community level,” said an official at another veterans charity, who asked to remain anonymous because of his group’s public dealings with IAVA. “They do everything at a national level and through the Internet. That’s not the same as meeting with members in person.”

IAVA staffers agree that it’s not the same. They believe it’s better.

“This is sacred ground for the people who use it,” said Jacob Worrell, special projects coordinator for IAVA. “For our veterans, they know this is a place where everyone knows everyone, and they can reach out to other veterans safely. When they log in, they know someone is watching out for them and cares about them. And we know this forum has saved lives.”

Worrell said Community of Veterans also serves as a sounding board for IAVA leadership, even though civilian employees have only limited access to the site. Staffers monitor conversations to see what problems veterans are having with their benefits and what news topics are resonating with the group.

Rieckhoff acknowledges the online model is very different than the one followed by established veterans groups with large support staffs and neighborhood posts dotted across the country.

“But we don’t want to be redundant with our services,” he said. “Things like Community of Veterans allow us to have a big impact with a small budget and a small staff.

“And our members use it. It’s an evolution of veterans culture. We think the VA could learn from that.”

Commanding attention

Rieckhoff is not afraid to make bold and pointed statements.

Much of the behind-the-scenes criticism leveled at the group focuses on him, the founder and director of the group. Several people interviewed said they will start supporting IAVA the day he leaves.

Unlike many other veterans organizations, IAVA does not elect its leadership. Rieckhoff is in charge until he decides to step away, or until the group’s board members pressure him to do so.

The 37-year-old vet is an imposing figure, with a loud voice and an air of confidence. He’s a New Yorker by birth and by reputation, unafraid of offending others with his blunt assessments.

He’s a natural at politics, able to quickly connect with people on a personal level and yet still command the attention of an entire room. At press events on Capitol Hill, he’s the center of attention even when he’s not the one speaking.

Rieckhoff was an Army reservist in 2001 and took part in rescue and security operations at ground zero following the Sept. 11 attacks. He deployed to Iraq in 2003 and returned home with the goal of starting a veterans advocacy group.

He’s a columnist for the Huffington Post, and a regular at the trendy TED conferences, founded with the goal of bringing together the world’s top thinkers to find “ideas worth sharing.” On Twitter — he logs into the social media site almost hourly — he describes himself as “Observer of things. Social entrepreneur, activist, advocate, writer” before ever mentioning IAVA.

In recent months, he has used the networking site to call out Shinseki on veterans benefits delays, his lack of public press appearances and the secretary’s decision not to sit down in person with IAVA leadership. The terms “VA” and “failure” appear frequently together on his Twitter feed.

“What we have seen is that our members expect a lot,” Rieckhoff said. “We’ve been hard on every VA secretary. The VA is improving, but things like the [benefits] backlog are ridiculous at this point.

“We’re trying to get attention, and create a national dialogue on veterans issues.”

Ammo for critics

His high profile makes Rieckhoff an easy target.

Earlier this summer, the military blog This Ain’t Hell uncovered a photo of Rieckhoff from a 2004 Amherst College alumni magazine interview, showing him wearing a Bronze Star and a Special Forces unit patch.

The site — a frequent critic of IAVA — accused him of being a military fraud and a hypocrite in light of IAVA’s support of Stolen Valor laws. Others detractors followed suit.

Rieckhoff defended the medal as a paperwork mistake (it’s listed on some of his personnel paperwork, but not others). He asked for clarification from the Army on the status of the award, but received none. He bought his Bronze Star after being told he had earned the medal, but hasn’t worn it since that interview.

He blames the Special Forces patch on bad timing and enthusiasm. He sewed on the patch days after receiving an assignment to the unit, but pulled it off a few weeks later when that assignment changed. The magazine picture appeared in that small window of time.

That’s not typical procedure, especially for Special Forces. Some critics cried foul, but many just rolled their eyes.

“Would I do something like that? No way,” said another veterans advocate, who asked to remain anonymous. “But if it was anyone but Paul doing this, I’m not sure it would be a big deal.”

In his 2006 book “Chasing Ghosts,” Rieckhoff wrote that his post-military goal in life was to elevate the concerns of veterans, who he believed were being overlooked in the Iraq War debate.

“We weren’t tree-hugging peaceniks and we weren’t throwing medals at the White House,” he wrote. “We represented veterans proud to have served their nation at a time of war, but deeply concerned about the ways our leaders had mishandled that, created more enemies and jeopardized our national security.”

His first attempt at that was founding Operation Truth, a self-proclaimed nonpartisan veterans advocacy group that garnered attention for its pointed criticism of President George W. Bush’s decisions on the Iraq War. The group eventually morphed into IAVA, shifting more toward such issues as GI Bill benefits reform and mental health advocacy.

Still, for many in the veterans community, a group traditionally tied to the Republican Party, the organization is a liberal cheerleader during a time of polarized politics.

IAVA’s public support for repealing the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” law in recent years — when other veterans groups largely remained silent on the issue — only deepened that impression.

Rieckhoff chafes at that accusation that he’s a partisan tool, saying that his staff works hard to hold all policymakers accountable. But, despite the frequent shots at Shinseki, the group has seen a considerable increase from four years ago in access to President Barack Obama’s White House.

Future questions

Over the last year, IAVA leaders have made a concerted push to put faces other than Rieckhoff’s in front of the camera, to defuse some of the one-man-show perceptions.

They’ve also been touting alumni making names for themselves outside of the group. Tommy Sowers, the new VA Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, worked as a senior advisor to IAVA three years ago. J.R. Martinez was regular at IAVA events before winning “Dancing With the Stars” last fall.

Staffers say the group is more than one individual and even more than just the small handful of employees. It’s an evolving community, different than any other veterans group before. And none of them are sure exactly where the group is headed in future years.

“Do we need to have a chapter in every city in America? I’m not sure that’s a path to success for a veterans group today,” said Tom Tarantino, who recently took over as chief policy officer for IAVA.

“The [overall] veterans population is shrinking dramatically. I don’t know if building posts everywhere is a model for the future. But if we don’t have a strong veterans presence in the civilian community, then people are going to forget we exist.”

Staffers believe that message of urgency sets them apart from some of the legacy veterans organizations, and spurs them to be more creative with new projects.

Last fall, IAVA teamed up with J.C. Penney Co. to give $1 million in new civilian clothes to returning war heroes, in contrast to the charity clothing donation drives held by groups like AMVETS and the Military Order of the Purple Heart.

This summer, IAVA launched an online “Defend the GI Bill” advertising campaign slamming for-profit schools, while other veterans groups pursued behind-the-scenes solutions.

“Now is not the time for us to tread lightly,” Tarantino said. “If I burn bridges but get results for my soldiers, I’m OK with that.”

Rieckhoff echoed that philosophy. He wonders how much of a media favorite the group will be in two more years, after most U.S. troops have left Afghanistan and most of the national discussion has shifted away from the military.

“We don’t assume that everyone is always going to care as much about veterans as they do now,” he said. “We’ve got to do as much we can with the attention that we get now to get things done.”

shanel@stripes.osd.mil Twitter: @LeoShane