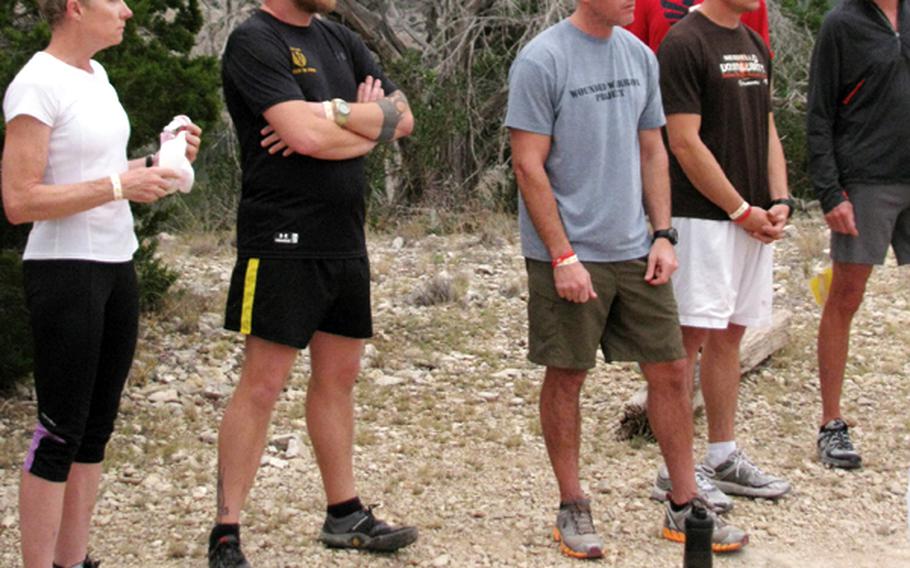

Army veteran Jim Buzzell (second from left) and other participants at Team Red, White & Blue's November running camp pause to listen to instructors before a three-mile training session. (Leo Shane III/Stars and Stripes)

OUTSIDE ROCKSPRINGS, Texas — Jim Buzzell is one scary veteran.

He hears voices. The antipsychotics he takes quiet them sometimes, but not always. His other medications usually keep him calm around strangers, but he did threaten to murder a vacuum salesman who knocked on his front door in October.

The 34-year-old gets belligerent when his wife doesn’t remember the imaginary conversations they never had. He broke down, sobbing and screaming, when a nurse he didn’t know walked into the examination room for his routine checkup. He starts to tug his hair and shakes a little just talking about his injuries.

His Army build, foot-long tattoos on his arms and legs and bushy beard only add to the intimidating stereotype.

For the last three months, Buzzell has kept himself on partial home confinement in South Carolina, saying even short trips to the post office down the street are too overwhelming. He thinks his traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder are getting worse.

But here, surrounded by complete strangers in the remote hills of West Texas, that Jim Buzzell disappears.

Thousands of miles from home, at a running camp with about 100 hard-core athletes, this Jim Buzzell is a social butterfly. He stops people to quiz them about their shoes. His hand goes up to volunteer at every request. He joins random conversations and immediately clicks with everyone.

Buzzell runs a chapter of the veterans advocacy organization Team Red, White & Blue back home, bringing together veterans and civilians for races and other athletics. That helps him relax, too. But it’s not usually this many veterans, or this many civilians, or this much fun.

He’s laughing, a lot. As the group runs down into a nearby canyon, you can hear him joking and guffawing as he keeps pace. No one thinks he has any problems, except for an old ankle injury he mentions in passing.

“It’s only here, it’s only running,” Buzzell said. “I know I’m not like this at home. It’s the only thing that stops the voices in my head.”

Only a few people here know about the voices. Most just think Jim is another nice guy.

That’s the whole idea behind this event and others organized by Team Red, White & Blue. The group’s mission is to “enrich the lives of veterans by connecting them to their community through physical and social activity.”

Founder Mike Erwin jokes that it’s an insurgency model for introducing veterans to Americans who know little about the military.

“Meeting new people isn’t easy,” he said. “Veterans are already in the community, but we want to give them a chance to really connect with others. If we can do that, it helps move from a military career to their new life in the civilian world.”

Team RWB surveys have shown about 60 percent of servicemembers don’t move back to their hometowns after they leave the military. With almost 1 million troops expected to leave the service in the next five years, that creates the potential for a flood of lonely, disconnected veterans across the country.

Over the last two years, the group has held relay races, bicycling clinics and even a yoga camp to bridge that gap. November’s elite running camp was the largest event to date, with more than 100 civilians, veterans and active-duty troops coming together in Texas.

Several of the civilian runners admitted they weren’t sure what to expect from the military marathoners, either for ability or demeanor.

“I was expecting a lot of ‘yes, sir’ and ‘no, sir’ from these guys,” said Daniel Murphy, an ultramarathoner from Houston. “I’ve never really known many veterans. But just hanging out with them, they aren’t like that. It’s pretty cool.”

Fellow Houston runner Nicholas Forge said he worried that “maybe you wouldn’t understand these guys, or maybe they’d have some psychological issues.” He also doesn’t have any close friends or co-workers who are veterans.

“But these guys are friendly and great. They’re normal,” he said.

Normal is something that Buzzell has been chasing for months. He was medically discharged from the Army early this summer, six years after a roadside blast in Iraq seriously injured almost every part of his body.

“There was an (explosive ordnance disposal) unit that was supposed to detonate an IED, but something went wrong and it went off early,” he said. “I was too close.”

The blast tossed Buzzell forward in his gunner mount. He broke his shoulder and severed his thumb tendon when he hit his weapon. He pinched nerves in his neck and re-aggravated a host of leg injuries. And his head smacked hard against everything.

Buzzell already had problems with concussions during his deployment, but that blast pushed him over the edge. Time healed his shoulder and neck, but brain injuries only grew.

He was assigned to training and teaching jobs back stateside while doctors managed his medications. Buzzell said he wasn’t fond of the work, but he still enjoyed being a soldier.

“Since I was medically discharged, it’s been really bad,” he said.

Buzzell said he doesn’t know whether the separation led to his depression, or whether the excitement of his daughter’s birth this year turned up his post-traumatic stress, or if the swelling in his brain has just gotten worse. But he’s frustrated and worried his doctors won’t find answers.

So he runs, a lot.

Some sessions approach 10 miles. Buzzell said he has walked out of the house mid-argument with his wife, Amy, to blow off steam, and returned hours later exhausted but calm. It used to upset her, he said, but she now understands a little better why he needs the time to relax himself.

Buzzell said running makes him focus on nothing more than putting one foot in front of the other. It hurts his neck, back and legs, but often they’re already aching. He doesn’t get a runner’s high — he gets a runner’s numb.

Murphy spent half of the running camp weekend trying to convince Buzzell that he could easily become a 50-miler, an exciting idea for the veteran. They traded analysis on water bottles and trail food and the worst races they’ve run.

“This is the Jim Buzzell I know,” said Dustin Levijoki, a longtime friend of Buzzell’s, as he watched the conversations. “All the stuff he has been going through, it’s been tough for him. But this is Jim. He’s a friendly, outgoing guy. He hasn’t been able to do that for a while.”

David Hanenburg, an instructor at the camp and the founder of endurancebuzz.com, said the idea of bringing veterans and extreme runners together for the event made perfect sense. Both are tight-knit, loyal communities, existing just outside mainstream America.

“There’s just something about sharing this kind of physical activity with new people, and an instant bond that develops,” he said. “If you can get through a long race, you’re part of the club. It’s welcoming, no matter who you are.”

Athletes at the camp shared not only their trail strategies but also their personal motivations for running. For some it’s a spiritual release. Others raise money for causes like breast cancer research.

Maj. Dana Riegel said she uses the memory of colleagues lost in Iraq and Afghanistan to push her the extra mile. Not only does it keep her moving, but it also gives her a chance to share their stories with civilians who might not always think about the wars.

She said her past involvement with Team RWB has helped her make new friends and keep in shape. She was recently reassigned to Alaska, and hopes to open a chapter there.

The group has about 4,000 members across 27 chapters, but at least one of those state organizations could be ending soon.

Buzzell is head of the South Carolina chapter, and he admits that organizing local events and maintaining a useful Facebook page is too much for him to handle right now.

He wants to stay active with the group, though, and has made travel plans for a few races with runners he met in Texas. If he can figure out a way to bring this camaraderie back home with him, maybe he can recruit a few people to join and run the chapter.

“I’ll still be running, no matter what,” he said. “If it’s just me going out there each Saturday with a Team RWB sign looking for more people, I’ll still do it.

“I’ll be out there, because I still have to run.”

shanel@stripes.osd.mil Twitter: @LeoShane