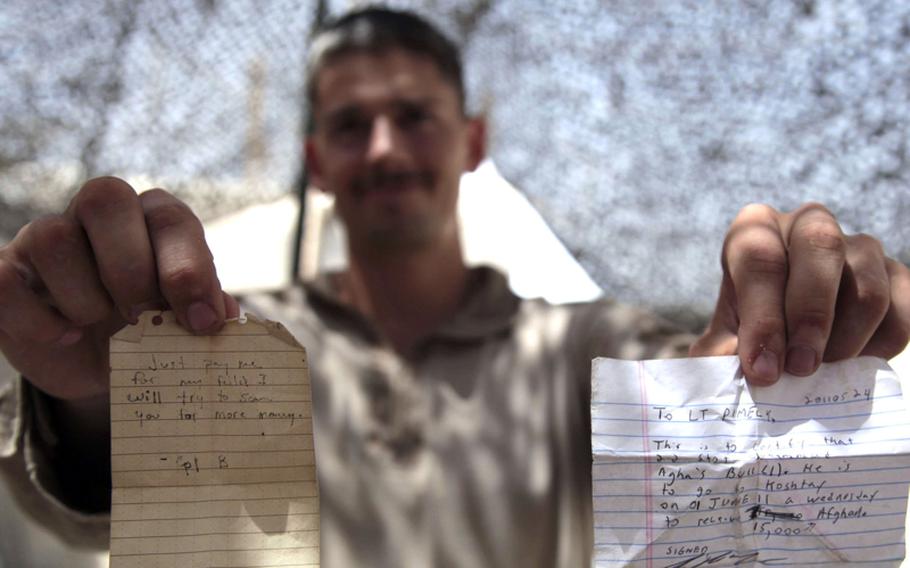

First Lt. Chad Pimley, a 24-year-old forward observer pulling double duty as a civil affairs officer, displays two notes written by Marines and given to Afghans who were requesting compensation for damages. (Matt Millham/Stars and Stripes)

GARMSIR, Afghanistan — The last orange rind of sun had just slipped past the horizon when an Afghan with a garland of ratty beard rushed to catch up with Marines on patrol north of Patrol Base Koshtay.

Like a patient surrendering a prescription to a pharmacist, he handed a creased rectangle of paper to Sgt. Chad Pauls. Written in the hand of a Marine from a different base, it said that somebody would take a look at the man’s canal.

“We don’t have time,” said Pauls, a squad leader from Richland Center, Wis., observing the diminishing quality of the day’s light and passing the buck again. They were still a mile from base.

The man slumped in bewilderment as the Marines marched off into the start of night.

“Everyone here believes that notes are as good as gold, and if you get a note that means you got a project; you get this, you get that, you’re entitled to everything,” 1st Lt. Chad Pimley had explained earlier.

A forward observer pulling double duty as the civil affairs officer for Company B, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, it’s Portland, Oregon’s Pimley who winds up with every note the company’s Marines write.

He has a couple from a guy who keeps pressing the Marines to pay him rent for the simple fact they built a base near his house. “Just pay me for my field,” reads one. “I will try to scam you for more money.”

Another bears a shepherd’s plea for restitution after a stray dog killed one of his sheep.

One legitimate claim’s note leaves out the details of why a Marine shot Mohammad Agha’s bull. The beast, which might have been on the Taliban payroll, was chasing him, so he shot it in the hoof to keep from getting gored. The wound proved fatal.

Phantom fire

Pimley’s favorite, though, is a shaggy-dog story jotted in the skeptical hand of a corporal who’s seen local residents try to get over on Marines too many times. Pimley didn’t realize until telling the story that he’d somehow lost its corresponding note.

“I can’t believe I got rid of that thing,” he said, throwing up his hands after a long search. “That’s all I wanted from this stupid country.”

He relayed the tale and the note’s contents to the best of his recollection.

It started when a vehicle sped toward a Marine checkpoint, ignoring signs to stop. The Marines, following procedure, fired a warning flare.

The vehicle stopped. The wind blew. The flare, dangling on a miniature parachute, came down in a field of wheat stubble. The stubble caught fire.

With the farmer’s help, the Marines stomped it out before any standing wheat burned. The farmer was grateful, Pimley said.

“So the patrol leader said, ‘Great. Well, here, can you sign this saying that you don’t need any compensation?’ ” The farmer replied, “ ‘Oh, no, no, no. I need compensation.’ ”

So the squad leader told him to visit Pimley at Patrol Base Koshtay. Instead, he showed up at another base where he told a Marine corporal who was unaware of the incident a wild tale of a blaze in which much was lost.

Like the squad leader, the corporal told him to see Pimley at Koshtay. The farmer wouldn’t leave without a note; so the corporal gave him a note.

The farmer had no idea what it said, but happily walked to Koshtay and handed it to Pimley.

“I got it, and I just couldn’t hold back laughing,” Pimley said.

The note read something like, “This guy’s just trying to scam you. Please give me lots of money because I lost all of these mythological things in a fire that didn’t really occur,” Pimley said.

The blaze was real, but the farmer’s yarn had grown legs. A few rugs he used to beat down the fire were in fact singed, but he claimed he also lost a watch.

Waving his arms as he explained this, Pimley caught a glint of metal on the farmer’s wrist.

“I said, ‘Oh, it’s OK, I found it for you. It’s right there,’ ” and pointed to the farmer’s wrist. The farmer quickly changed his story.

“Obviously, we try to reimburse people for any battle damage that … may have happened because of us,” Pimley said.

So he paid for the rugs. But he wasn’t buying any watches.