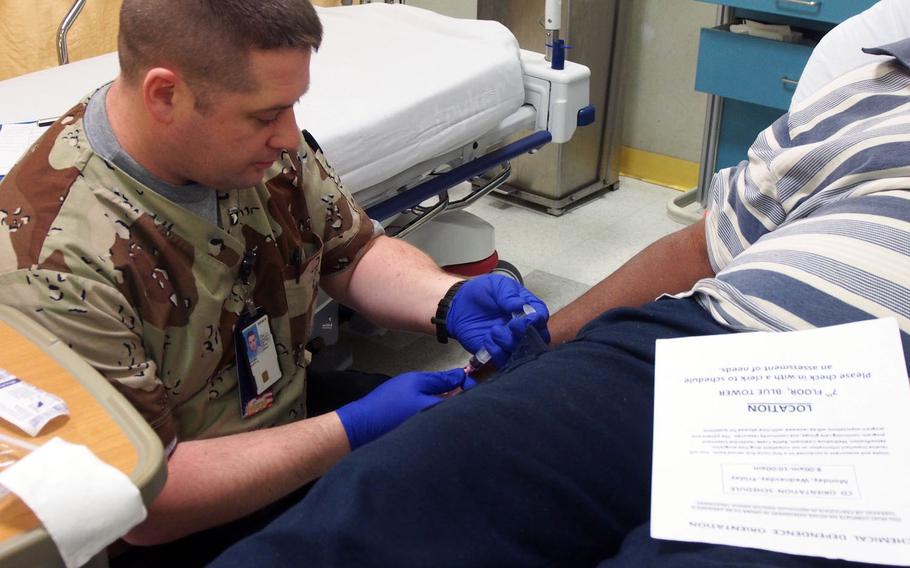

Former Army medic Scott Garbin takes blood from a patient at the John Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit. Garbin is part of a group of former medics and Navy corpsmen participating in a Department of Veterans Affairs program to place them in healthcare jobs at VA hospitals. (Heath Druzin/Stars and Stripes)

NORTH CHICAGO, Ill. — In four deployments as an Army combat medic to some of the most dangerous corners of Iraq and Afghanistan, Joe Carney had seen the worst of war — bullet wounds, severed limbs, shrapnel. He saved lives amid bombs and gunfire, his emergency room often a patch of dirt in the desert or a rocky mountainside. None of that mattered when he left the Army three years ago.

“I think the services should do a better job because at the end of the day, your last day in the Army, the last day in the Navy, you’re out, no one cares about you,” he said. “What I tell people who are planning to get out is, you have to have a plan.”

Like many medics and Navy corpsmen, the U.S. military’s front-line medical professionals, Carney’s skills translated to almost nothing in the civilian world.

He grew up watching “M.A.S.H.” and “ER” with his parents and was drawn to emergency medical work as a young boy. That led him to join the Army at 19 and serve as a combat medic for 10 years. Nearly half of that time was spent deployed in war zones.

But despite his extensive training, he lacked state licensing certificates and he struggled to find a job at his skill level. He settled on a job as an emergency room technician, where he was allowed to do little beyond administer oxygen and take blood pressure readings.

“It was a good reality check,” he said. “You know you’re not in the military no more. The hard part was standing back when you’ve got these trauma situations.”

It’s a common story with medics and corpsmen, who have long had difficulty finding civilian medical work that matches their training.

“It is an asset that’s being wasted because they’re highly skilled in what they do,” said Dr. Michael Bellino, an emergency physician who mentors Carney at the Capt. James A. Lovell Federal Health Center in North Chicago, Ill. “I’d trust him with taking care of my family.”

Carney, 32, doesn’t have to stand back anymore. For the past two years, he has been working in a fledgling program that offers medics and corpsmen appropriate health care employment and at the same time, builds up the ranks at the Department of Veterans Affairs — which is struggling mightily to keep up with demand. He and about 45 other veterans are working as Intermediate Care Technicians, a role invented for the VA program. Carney is also in a pilot program to prepare ICTs to become physician assistants, a more advanced, higher-paying job.

State standards

According to the most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers, post-9/11 veterans have a slightly higher unemployment rate than their civilian peers and veterans as a whole. While there are no specific unemployment numbers for medics and corpsmen, they leave the military with very specific barriers to employment in the medical field.

Despite being trained to tend to bullet wounds and severed limbs in the harshest conditions, under fire and on helicopters, most leave the service without a certificate for the lowest-rung medical jobs. They face months of redundant training, and many leave the medical field.

“We do a little more than what people may understand,” said Scott Garbin, a 15-year Army veteran who works as an ICT in Detroit and is the unofficial senior technician in the program, acting as a liaison between the veterans and the VA.

Congress has passed legislation to allow the federal government to recognize military training for some civilian jobs, but health care licensing is generally done at the state level, and efforts have been uneven across the country. Some states have made efforts to recognize military training; in California, former medics and corpsmen can take an equivalency exam to speed the process of becoming EMTs or paramedics. A small program at Lansing Community College in Michigan, which was lauded as a model at a recent military credentialing conference in Washington, fast-tracks former medics to get paramedic licenses and placement in a nursing program.

“One of the major roadblocks those separating from the military face in their transition to the civilian job market is the fact that many professional licensing and credentialing standards vary from state to state,” Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., chairman of the House Committee on Veterans Affairs, said in an email. “I urge states to adopt standards that will fully recognize veterans’ experience, and I will continue to support VA’s programs putting these professionals to work helping their fellow veterans.”

Undervalued experience

Medics and corpsmen are exposed to more trauma than just about any other occupation in the military. They get an up-close view of the carnage and often must work to save the lives of their friends. Some civilian employers who don’t understand what they’ve been through penalize them for their experiences.

“I even had one hospital’s emergency room (official) ask me, ‘How damaged are you?’ ” Carney said.

The civilian reaction to combat experience has been one of the most difficult changes to make, said Ed Davin, an analyst with the research firm Solutions Information Design, who has spent three decades studying military-to-civilian career transitions and helped develop government programs to aid veterans as they leave the services.

“What the civilian folks can’t get their arms around is, ‘How do I put a value on two tours in Iraq?’ ” he said.

The medical community has made strides in recognizing military training, and the military has improved its credentialing, but the vast majority of medics and corpsmen still come out facing the prospect of a pay cut or redundant training.

“We have large numbers of medics and corpsmen who, when they come out, can’t get a job to support a family,” he said.

‘They relate’

When Aaron Rice left the Army in 2009, he was 25, a veteran of three violent deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan as a combat medic. He was struggling to find his footing in the civilian world. Seeking solitude, he moved to Alabama, far away from friends and family.

“It was kind of like looking in a broken glass mirror,” he said. “Your sense of self is kind of lost because your sense of self was your unit.”

His colleague, Conrad Siat, had a similar experience after a year in Ramadi, one of the most dangerous corners of Iraq. He had to quit a construction job because the loud noises bothered him, and he was later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Both got help, and now they work together as technicians at the John Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, one of 15 VA centers affiliated with the ICT program. On a winter day in that hospital’s busy emergency department, they attended to patients, including an ill elderly Korean War-era veteran and a young Iraq veteran with a gaping wound in his arm.

Rice and Siat say the job has become a calling.

“I’m a veteran, I’m here for the veterans — they’re my brothers,” Siat, 44, said. “He who sheds his blood with me shall forever be my brother.”

Far from seeing war experiences as liabilities, VA officials say having veteran medical professionals interact with their patients is an obvious benefit. Doctors who work with the technicians say they have a special rapport with patients and can often calm combative patients who might not respond to civilians.

“They relate,” said Dr. Bassam Batarse, the Detroit VA hospital’s chief of staff for integrated clinical services, who says the program has gone so well he’s requested additional technicians.

Positive response

The ICT program began in 2012 after prompting from then-Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki. When the VA central office began accepting applications for 45 spots, they received about 400 applications, said Karen Ott, director for policy, education and legislation in the VA’s Office of Nursing Services.

“We knew we were on to something,” she said.

Now there are 45 ICTs working across 15 VA hospitals, and the program is set to grow to about 270 slots. Pay for technicians can range from $31,000 to $52,000, depending on experience and location. The pilot program to help technicians prepare for physician assistant school while on the job, called CAMVETs, has just started. .

Navy Lt. Cmdr. (Ret.) David Lash, the director of the Corpsman and Medic Vocation Education and Training Program and a civilian physician assistant, said the job matches well with the skills of medics and corpsmen. It will also be open to those interested in other health care jobs, including physician. The physician assistant position was created in the mid-1960s partly in response to Vietnam veterans who returned with skills in treating trauma. As the profession has become more popular, it has become harder for medics and corpsmen to get into school.

Lash, who helped create the ICT program and the Lovell Health Center-based CAMVETS, bridges the divide between civilians who run those schools and the technicians.

“A lot of schools don’t want to accept what they did in the military as health care experience, which is crazy,” he said.

He has gotten a positive response from schools he’s worked with, and he hopes to be able to tailor the program to veterans interested in using the ICT job as a stepping stone to other medical jobs. Lash said interest in the program from veterans has been overwhelming, and he wants to take it national.

“How can you go wrong if you have veterans becoming the people who are taking care of our veterans?”

druzin.heath@stripes.com Twitter: @Druzin_Stripes