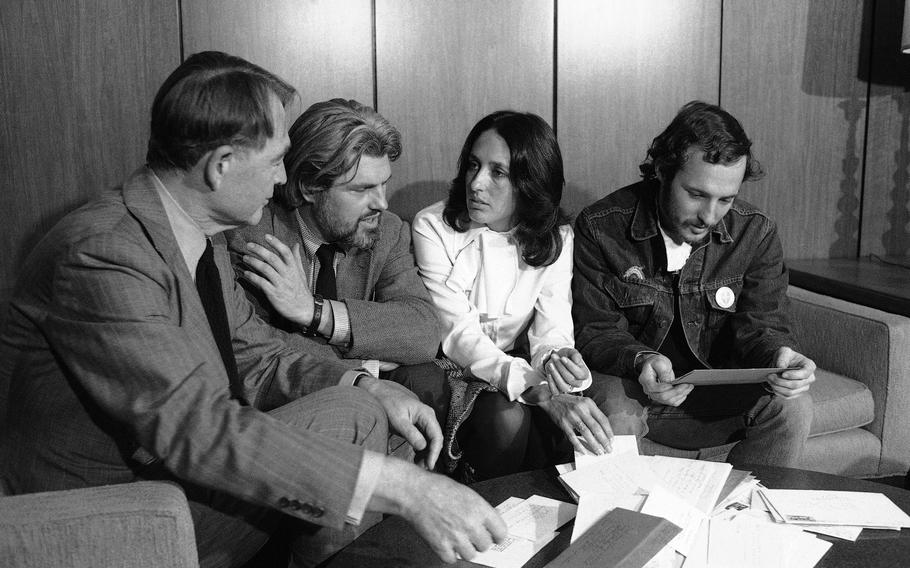

Four Americans show letters from families of prisoners held in North Vietnam, Dec. 13, 1972, before departing New York's Kennedy Airport for Hanoi, where the letters will be turned over to the Committee of Solidarity with American People. The group includes, from left are: former Brig. Gen. Telford Taylor, who was chief U.S. counselor at the Nuremberg war trials; Rev. Michael Allen, of Yale Divinity School; folk singer Joan Baez; and Barry Romo, of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. (Dave Pickoff/AP)

Barry Romo, a former Army officer in the Vietnam War who became a leading antiwar organizer and bore witness to devastating U.S. bombing runs on Hanoi during a 1972 visit to North Vietnam with activists including folk singer Joan Baez, died May 1 in Chicago. He was 76.

His death was announced by Vietnam Veterans Against the War, a group for which Romo served as a national coordinator for more than four decades. A spokesman, Roberto Clack, said Romo had a heart attack at home and was taken to a hospital, where he was declared dead.

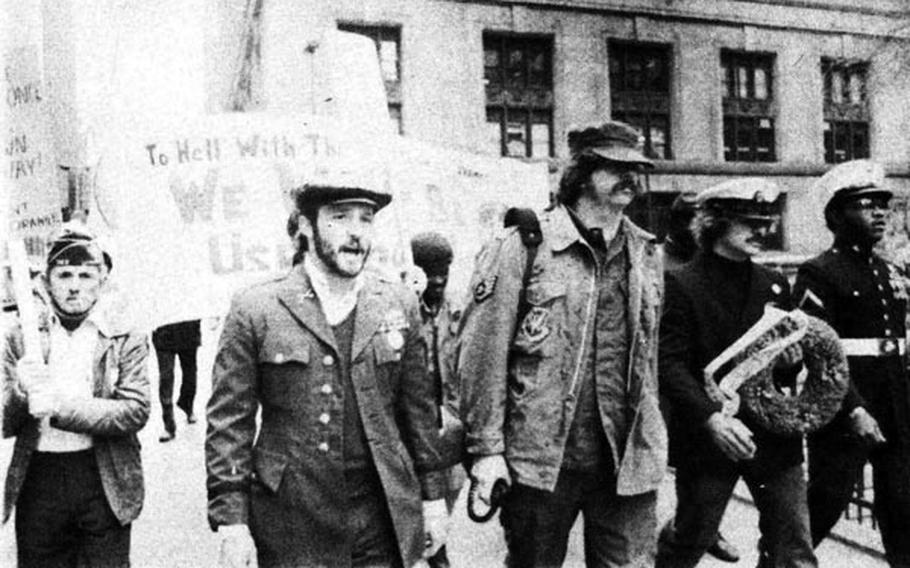

During the height of the antiwar movement, Romo was a prominent voice among former military members who challenged Pentagon and White House narratives of a conflict that was winnable and necessary. Romo and other veterans - often wearing their old uniforms and fatigues - also added powerful symbolism to the wider protests by students, draft resisters, religious groups and others.

In April 1971, Romo organized convoys to bring thousands of veterans to Washington for an antiwar encampment known as Operation Dewey Canyon III, named after two U.S. military operations seeking to strike North Vietnamese bases. The veterans, camped on the National Mall, attended Senate hearings and staged rallies at Arlington National Cemetery and outside the Supreme Court and Pentagon.

On April 23, Romo joined hundreds of the veterans who lobbed their medals, discharge papers and war mementos onto the Capitol steps. Romo, who fought in the 1968 Tet Offensive launched by North Vietnamese forces, hurled his Bronze Star Medal and Combat Infantryman’s Badge.

Standing near Romo was former Navy lieutenant John F. Kerry, also a leader of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. “I am not doing this for any violent reasons but for peace and justice, and to try to make this country wake up once and for all,” said Kerry, who later was a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, U.S. secretary of state and the 2004 Democratic presidential candidate.

Barry Romo, second from left, and Bill Davis in Chicago marching with Vietnam Veterans Against the War on Veterans Day circa 1970. (Vietnam Veterans Against the War)

After Romo and many of the veterans had left Washington, massive antiwar marches paralyzed many parts of the city on May 1. More than 7,000 people were arrested in what became one of the largest street confrontations of Vietnam era.

Yet the sight of the veterans’ medals clanking on the Capitol’s marble steps became one of the defining scenes from the weeks of protest - at a time when public opinion was increasingly questioning how long the war could drag on and at what cost. Four years later, the capital of South Vietnam, Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), fell to the North Vietnamese.

In an essay in 1988, Romo looked back on the protest at the Capitol - “painful and angry thoughts filled our minds” - and recounted the death of nephew Bob Romo, who was killed by a North Vietnamese sniper in May 1968. “He drowned in his own blood,” Romo wrote.

He often retold the story of his nephew. For Romo, it was a key moment in his evolution from an eager Army enlistee to an antiwar leader. Romo signed up in 1966 as a supporter of the war. “I bought all the lines,” he recalled. His nephew was later drafted and put in an infantry brigade under Romo, who rose to become a first lieutenant.

“[My nephew] begged me to help him get out of the field,” Romo told NPR’s “Morning Edition.” “But I couldn’t help him.”

When his nephew was killed on patrol, the body couldn’t be recovered for 48 hours because of North Vietnamese fire. Already, Romo said his view of the war had changed, seeing the destruction of villages and the growing enmity at the U.S. military even among South Vietnamese. The death of his nephew was a tipping point.

“My mind started to change when I could see the people didn’t give a damn, our allies didn’t want to fight and senior officers flew around in helicopters while we ran around the jungle with barely enough water to drink,” Romo told the Chicago Tribune in 1996. “My nephew’s death made me face the reality I was killing people for all the wrong reasons.”

After leaving the battlefield, Romo oversaw a training company at Fort Ord in California and was honorably discharged in January 1969. He soon became active in antiwar marches and veterans’ actions, and he was among more than 100 former military personnel at an event in Detroit in early 1971 to offer accounts of alleged military abuses and atrocities by U.S. forces.

The gathering, known as the Winter Soldier hearings, was also among the first forums to discuss the extent of psychological scars, including post-traumatic stress disorder, on veterans.

“Our slogan was ‘honor the warrior, not the war,’” said Romo, who began work in the national office of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1972. “It was important to overcome those kinds of differences.”

Romo returned to Southeast Asia in December 1972, traveling to the North Vietnamese capital, Hanoi, with Baez; Michael Allen, an associate dean at Yale Divinity School; and former Army Brig. Gen. Telford Taylor, a chief prosecutor at the post-World War II Nuremberg trials who became a staunch critic of the Vietnam War. Romo carried Christmas presents and letters for more than 500 U.S. prisoners of war.

During the two-week stay, the United States opened an intensive bombing campaign on the city even as peace talks were underway in Paris. The airstrikes were “worse than anything I was under in London during the blitz,” Taylor said.

The group said the bombing damaged civilian sites, including a 950-bed hospital. At one point, Romo and the others saw a woman digging in the rubble of the building in a residential area of Hanoi, shouting, “My son, my son, where are you?”

Much of Baez’s 1973 album “Where Are You Now, My Son?” was based on what the group experienced in Hanoi.

Barry Louis Romo was born in San Bernardino, Calif., on July 24, 1947. His father, a World War II veteran, worked as a meat cutter. His mother, who was born in England, was a homemaker. The couple met during the war.

Romo enlisted in the Army after graduating from high school and was sent to Vietnam in 1967 as a second lieutenant.

After the war, Romo helped guide Vietnam Veterans Against the War into other roles, including pressing for greater health-care coverage for people exposed to the military defoliant known as Agent Orange.

Later, Romo helped efforts in 2006 to establish an allied group, Iraq Veterans Against the War. He worked for the U.S. Postal Service, including as a local union leader, and retired in 2009.

His marriage to Alynne Kilpatrick ended in divorce. Survivors include two children.

In Romo’s apartment in Chicago, the walls had posters from antiwar events during the Vietnam years. There were also newspaper clipping and printouts of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“It would be nice to move on,” he once said. “But history keeps repeating itself.”