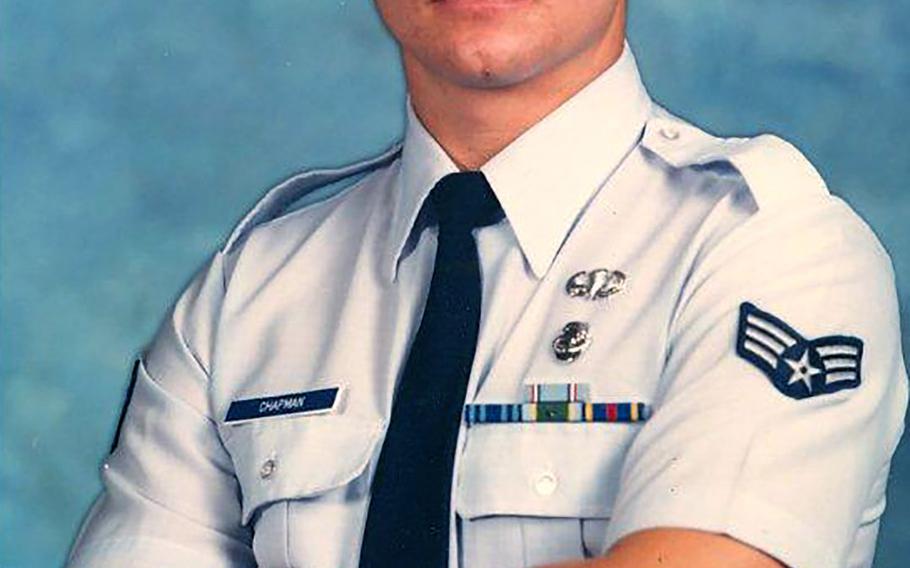

Tech. Sgt. John A. Chapman, shown at the rank of Senior Airman, will be the 19th Airman awarded the Medal of Honor since the Department of the Air Force was established in 1947. (U.S. Air Force)

WASHINGTON — Stranded alone atop a snow-covered Afghanistan mountaintop, suffering from multiple gunshot wounds and surrounded by hundreds of al-Qaida militants, Tech. Sgt. John Chapman used his final moments of life to ensure other American troops had a chance to survive.

The Air Force combat controller — believed dead when his comrades fled the mountaintop amid heavy fire — stirred himself from unconsciousness to fight off enemy attackers for an hour before a helicopter carrying an assault force of Army Rangers approached. That’s when Chapman, from the protection of a chest-high, World War II-style pillbox bunker, did the unthinkable — he charged forward, turning his back on an enemy machine gun and fired on two fighters preparing to launch rocket-propelled grenades at the incoming Chinook.

For that action, his final in a series of heroic deeds atop Takur Gar mountain on the night of March 3 through the morning of March 4, 2002, President Donald Trump presented his family the Medal of Honor during a White House ceremony Wednesday afternoon.

Trump noted Chapman became the first airman to receive the nation's highest military honor for actions after the Vietnam War and he also was the first Air Force special tactics expert to ever receive the medal.

The president hailed Chapman as a “great warrior,” as he recognized nearly a dozen individuals in attendance at the East Room ceremony whose lives were saved on the mountain by Chapman’s actions.

“John gave his life for his fellow warriors,” Trump said. “Through his extraordinary sacrifice, John helped save more than 20 American servicemembers.”

The award is an upgrade of the Air Force Cross that Chapman was awarded posthumously in the months after the brutal fight now known as the Battle of Roberts’ Ridge during the early months of the war in Afghanistan. For years, some Air Force officials believed Chapman deserved the Medal of Honor, suspecting he had lived and continued fighting after his comrades from the Navy’s SEAL Team 6 had left the battlefield. But until a massive 30-month investigation into Chapman’s actions was completed in recent years that went unproven.

For his family, the Medal of Honor simply serves as confirmation of Chapman’s selfless final moments, acts his widow Valerie Nessel said she was not surprised to learn. Her husband of 10 years, she told reporters, always put his team before himself.

“It’s just an amazing honor. It’s been a long road coming,” Nessel said Tuesday. “But it doesn’t change anything as far as [our] pride. We’ve always been proud of him. This doesn’t make us any more proud of him. It just validates what was done on that mountain that day.”

On Wednesday, after posing for photographs with Trump and her late husband’s medal presented in a wooden-framed box, Nessel smiled broadly, mouthing “thank you” to the president before kissing him on the cheek.

New evidence For years, at least officially, Chapman’s story ended when Master Chief Petty Officer Britt Slabinski, the leader of the SEAL team with which Chapman had assaulted Takur Gar mountain, ordered his outmanned, outgunned and heavily bloodied team to withdraw, leaving Chapman’s and fallen SEAL Petty Officer Neil Roberts’ bodies behind on the mountain for the Ranger team to try to recover later. Slabinski, who received the Medal of Honor for his own actions earlier in that battle, has said in recent months that he still believes Chapman was already dead when his team was evacuated.

Slabinski, who attended the ceremony Wednesday, has long credited Chapman with saving the lives of his teammates at Takur Gar and endorsed him for the Medal of Honor.

A review of Chapman’s Air Force Cross was ordered in 2016 and evidence compiled by a team of 17 Air Force special operators proved Chapman did live longer and he also continued to fight and likely intentionally gave his own life to give others a better chance to survive the fight. The review was part of a Pentagon effort to determine whether some 1,100 post-9/11 valor awards merited upgrades.

The review relied heavily on grainy, black-and-white video footage captured by an MQ-1 Predator drone overhead throughout much of the fight, an Air Force special tactics officer involved in the investigation told reporters last week at the Pentagon. The officer spoke on the condition of anonymity to provide a detailed explanation of his team’s findings.

What the team found was “awe inspiring” and left little doubt that Chapman’s actions deserved the military’s highest honor for battlefield valor, the officer said.

In addition to the drone footage, the Air Force combed through intelligence reports, reviewed autopsy results and terrain analysis, and interviewed witnesses involved in the battle from the air and the ground to determine as completely as possible what occurred on Takur Gar after the SEALs left, the officer said.

Among the witnesses interviewed were Air Force AC-130 gunship pilots who observed evidence, such as infrared markers meant to identify friendly troops, that indicated there was a lone American servicemember fighting off enemy troops.

“John was the only American alive on the mountaintop and there was somebody there fighting for an hour,” the officer said.

A team of Army observers who watched the battle on Takur Gar from a mountaintop about four kilometers away reported similar observations, including hearing faint radio calls using the designation reserved for Chapman, MAKO 30 Charlie. No one else heard the calls, evidence indicates, the officer said.

Chapman’s actions Chapman’s Air Force Cross award was based entirely on witness testimony from four SEALs, including Slabinski, who were members of Chapman’s team, the Air Force officer said.

Chapman and the SEALs were sent late March 3, 2002 to Takur Gar to establish a reconnaissance position at the top of the mountain to enable a forthcoming conventional Army operation against al-Qaida fighters as part of Operation Anaconda, according to the award citation. The team had no idea that it was being sent into a hornet’s nest of enemy activity — a local headquarters of al-Qaida activity.

As the MH-47 Chinook helicopter ferrying Chapman and the SEALs to Takur Gar neared the mountain, it was hit by rocket-propelled grenade fire, knocking Roberts from the chopper into the enemy territory below. After landing and boarding a new helicopter, the team embarked on a mission to recover Roberts. Chapman led the charge, forging through thigh-high snow in the middle of the night to attack an enemy bunker, providing cover to his comrades as they rushed forward, Trump described Wednesday.

“John Chapman was the first to charge up the mountain toward the enemy. He killed two terrorists and cleared out the first bunker,” the president said of Chapman’s actions for which Trump approved the Medal of Honor some 16 years after the battle. “You couldn’t even see. So many bullets. At over 10,000 feet, they fought the enemy at the highest battle in the history of the American military.”

It was likely then that Chapman was first wounded and fell unconscious, said the Air Force officer who briefed reporters at the Pentagon.

But his actions after awakening, fighting for another hour, ultimately suffering nine gunshot wounds, including the final two fatal wounds from a heavy machine gun, is why his award was upgraded to the Medal of Honor, the officer said.

“And he really fought,” Trump said Wednesday. "We have proof of that fight. He really fought.” Evidence indicates Chapman battled at close range for an hour until the Chinook full of Rangers approached. It was at that point when he left the bunker in broad daylight to engage the enemy fighters preparing to fire RPGs. He likely was killed then, the officer said.

Chapman’s commander at the time, now-retired Air Force Col. Kenneth Rodriguez, believes Chapman knew he was unlikely to survive his final action.

“He knew the very immediate danger he was in,” said Rodriguez, who at the time commanded the 24th Special Tactics Squadron at Pope Air Force Base in North Carolina. “He sees the quick reaction helicopter coming in, and he came out from cover and exposed himself to very accurate enemy fire.

“He knew in his heart of hearts, I’m convinced, he knew what kind of danger he was exposing himself to, the enormous risk that he had placed himself in when he stepped out to defend that quick reaction force helicopter and the lives of those men on board.”

‘Team before self’ Nessel, Chapman’s widow, was only vaguely aware of her husband’s final actions as the Air Force conducted the unprecedented review of his Air Force Cross. When she learned precisely what he had done for his fellow servicemembers it hardly surprised her.

“Knowing John, I wouldn’t have expected anything less of him,” she said. “It’s team before self. I don’t think for a second he thought about doing anything but protecting the other men.”

Nessel, who had two children with Chapman, Madison, and Brianna, described her late husband as humble and kind.

People who met him outside of the military would likely never guess that he was among the service’s most elite trained killers, she said Tuesday.

“He was such a genuine and good-hearted person,” Nessel said. “He lived his life — team before person. An amazing man. And, he’d be a little embarrassed to be having this bestowed upon him.”

Chapman, who was 36 when he died, enlisted in the Air Force in 1985 as an information systems operator after his mother, Terry Chapman, steered him away from going into combat control.

“When he first went in, right from the beginning he wanted to go into the combat control field,” Terry Chapman said Tuesday. “I kind of talked him out of it when I found out how dangerous it could be.”

After four years in the service, he went to combat control training anyway, quickly establishing himself among the elite in the field.

He was selected to join the 24th Special Tactics Squadron, the Air Force’s most elite commando team. He deployed to Afghanistan as a team leader with the unit, charged with directing air power for his SEAL Team 6 comrades.

All these years after his death, Nessel said she believes her husband would have made the same decisions he did atop Takur Gar mountain if he had the chance to do it again. But Chapman would not have much cared for the attention that comes with receiving the Medal of Honor.

“John would be extremely humbled,” she said. “This medal would not just be about him, it would be for all of the men who were lost on that mountain. He would tell you, basically, ‘I’m just doing my job, just like any of my other brothers would be doing. I was just doing my job.’”

dickstein.corey@stripes.com Twitter: @CDicksteinDC