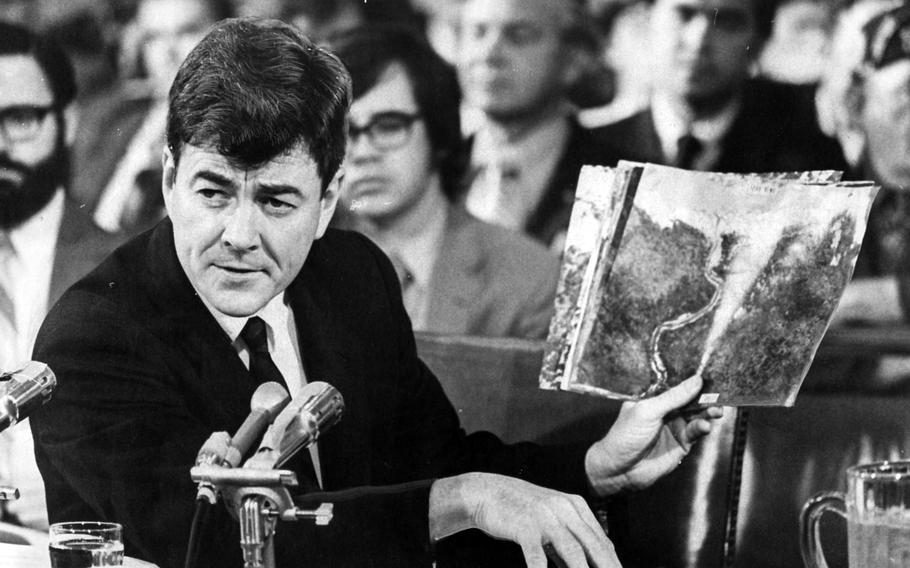

Rep. Paul N. “Pete” McCloskey (R-Calif.) shows aerial pictures of villages in Laos, testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee following a visit to Southeast Asia. (Linda Wheeler/The Washington Post)

Paul N. “Pete” McCloskey, a Republican congressman and decorated Marine who turned against his own party leader, President Richard M. Nixon, accusing him of expanding an “illegal” war in Vietnam and calling for his impeachment over the conflict while challenging him for reelection, died May 8 at his home in Winters, Calif. He was 96.

The cause was congestive heart failure, said family spokesperson Lee Houskeeper.

Before he drew national headlines for excoriating Nixon, McCloskey had been best known for defeating Shirley Temple Black, the former Hollywood child star, in a 1967 special election for a House seat representing what is now the Silicon Valley area of California.

During his tenure, which lasted until 1983, McCloskey became known to his admirers and detractors either as a principled maverick or as a gadfly firebrand. A Marine Corps rifle platoon commander during the Korean War, he received some of the military’s top awards for valor - including the Navy Cross and the Silver Star - and used his military credentials as leverage to steer his party away from hard-line conservative elements on issues including race relations and the environment.

Calling himself a “Teddy Roosevelt progressive,” he worked to gain passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, helped organize the first Earth Day that year and supported the Endangered Species Act of 1973. In the public eye, the defining issue for McCloskey became Vietnam and what he considered Nixon’s “immoral” conduct of the war. On visits to Vietnam in 1968, he ignored whatever hopeful predictions were still being issued from political and military leaders in Saigon and Washington. Instead, he sought out sergeants and lieutenants - men who were seeing combat first hand, as he had in Korea as a young officer. In January 1968, he returned from his first visit to Vietnam “with grave doubts that what we do there is right.”

The American military incursion into Cambodia in April 1970 and Nixon’s failure to answer several of McCloskey’s written inquiries turned the congressman into a fierce dissenter. With eight other members of Congress, McCloskey supported the national student antiwar protest of October 1969. He helped draft a motion to repeal the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution of 1964, a congressional measure that had authorized the president to widen military operations against North Vietnam, and became a leader in House efforts to disengage U.S. forces from Southeast Asia. In a Feb. 10, 1971, speech at Stanford University, his alma mater, McCloskey called for a “national dialogue” to discuss Nixon’s impeachment, a proposal meant to bring about a fundamental policy change on the war. McCloskey asserted that Nixon, like President Lyndon B. Johnson before him, had breached the Constitution “through the arrogant use of power” and that some of America’s tactics in Southeast Asia amounted to war crimes.

Six days after the speech, McCloskey elaborated on his views in a television interview: “We’ve lost the stomach to fight this war on the ground, and yet we think it’s appropriate that we can kill people by push-button bombing from 50,000 feet.” With an antiwar speech on the House floor soon after his talk at Stanford, McCloskey attracted more attention by asserting that “a reasonable argument can be made that the President’s recent decision to employ American air power in the neutral countries of Laos and Cambodia exceeds his constitutional powers.” He told journalists that, if a more politically seasoned Republican did not step up, he would run against Nixon himself.

Vice President Spiro T. Agnew called McCloskey, who was in the vanguard of the “Dump Nixon” movement, “a Benedict Arnold.” There was brief speculation that McCloskey might be “another McCarthy” in 1972, an allusion to Sen. Eugene McCarthy, the Minnesota Democrat whose strong showing as an antiwar presidential candidate helped drive Johnson from office in 1968.

But the political landscape was different in 1972. Nixon was winding down the Vietnam conflict, albeit far too slowly for his critics, and peace negotiations were inching along in Paris. The White House largely ignored McCloskey, who was met with stony silence from party eminences and never gained traction in the Republican primaries. Many voters who detested Nixon were gravitating to Sen. George S. McGovern (S.D.), the Democratic nominee, who was swamped by Nixon in the general election. In June 1973, as the Watergate scandal was unfolding, McCloskey again said the impeachment of Nixon should be considered, this time for obstruction of justice. The following summer, Nixon’s own tape recordings showed that he had engaged in a coverup. Faced with all but certain impeachment in the House and conviction in the Senate, he resigned on Aug. 9, 1974. Paul Norton McCloskey Jr. was born in Loma Linda, Calif., on Sept. 29, 1927. Like his father, a lawyer, he was also known as Pete. He grew up in South Pasadena, where he was a star on his high school baseball team. After Navy service from 1945 to 1947, he graduated from Stanford in 1950 and from Stanford’s law school in 1953. His education had been interrupted by two years in the Marines during the Korean War. As a rifle platoon commander in May 1951, he led a successful assault against a heavily fortified enemy hill position despite grievous wounds and continued to lead the charge until the bunkers were silenced, with 40 enemy soldiers killed and 22 captured, according to his Navy Cross citation.

A few months later, McCloskey received the Silver Star for a battle in which his platoon came under withering fire while making its way across a valley in support of a tank patrol. Eight of his men were struck down, and McCloskey sustained a severe leg wound, for which he refused treatment. Despite great loss of blood, he continued to direct his men’s evacuation to safety.

McCloskey, who became a lieutenant colonel in the Marine Reserve, also received two Purple Hearts; decades later, he gave one away to Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Calif.), saying she had not been publicly recognized enough after being ambushed and shot as a young congressional staffer while in Guyana to investigate Jim Jones’s death cult in 1978.

As a young lawyer, McCloskey set up a practice near Stanford and specialized in what he called “impossible cases”: defending gay people, members of minority groups and others who had trouble finding legal help. He took an early interest in cases involving conservation and environmental protection. McCloskey’s entry into public life could be traced in part to a 1963 White House gathering on civil rights to which he had been invited. He said the experience encouraged him to counter the rise of the John Birch Society and other extremist elements in the Republican Party. In 1964, he refused to support the hard-right campaign of Sen. Barry M. Goldwater (R-Ariz.) for president. That year, McCloskey co-founded the California Republican League to help the party regain some of its more liberal traditions. McCloskey was first elected to the House on Dec. 12, 1967, easily defeating Democrat Roy Archibald to fill an open seat. But the more notable contest was the Republican primary, in which McCloskey was the underdog against Black. Her lackluster campaign was not helped by bands playing “On the Good Ship Lollipop,” hearkening to her movie days. McCloskey’s first marriage, to Caroline Wadsworth, ended in divorce. He later married Helen Hooper, his onetime congressional press secretary. In addition to his wife of 42 years, survivors include four children from his first marriage, Nancy, Peter, John and Kathleen McCloskey; and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. McCloskey lost campaigns for the Senate in 1982 and for the House in 2006. Long opposed to the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, he registered as a Democrat in 2007. He continued to practice law and grow olives and oranges on a farm in the Sacramento Valley. And he continued to express revulsion over the state of national politics, noting the influence of “big money” that has made the United States a “militaristic and arrogant nation.” In 2014, when he was 86, McCloskey traveled to North Korea, hoping to meet men who had fought for their country. The former Marine had been haunted by memories of leading bayonet charges against enemy soldiers, some only teenagers, and seeing terror on their faces. A meeting was arranged with a retired three-star general, a man of McCloskey’s age. “I told him how bravely I thought his people had fought,” McCloskey told the Los Angeles Times, “and we embraced.”

Stout, a Washington journalist, died in 2020.