A health care worker places a dish of syringes near a vial of Covid-19 vaccine, produced by Pfizer and BioNTech, at a vaccination center in a town hall in Paris on April 9, 2021. (Benjamin Girette/Bloomberg)

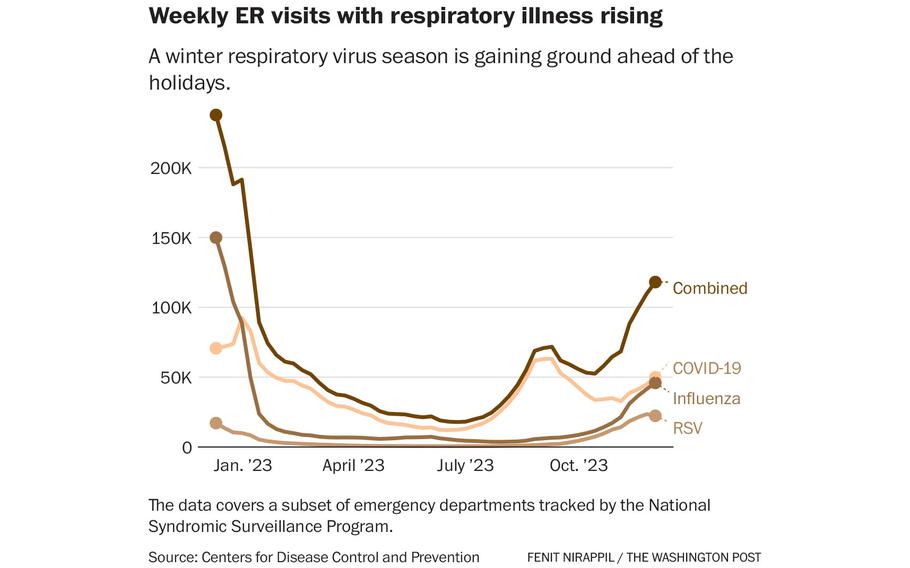

Respiratory viruses are rebounding in the United States on the precipice of the end-of-year holidays, with emergency room visits for COVID-19, influenza and respiratory syncytial virus collectively reaching their highest levels since February.

Among the three viruses, COVID continues to be the biggest driver of hospitalizations, settling into a familiar rhythm of causing periodic waves without wreaking havoc on the health-care system as it once did. Hospitals reported more than 22,000 new COVID admissions the week ending Dec. 2, the highest since the peak of the summer wave in September.

Compared with punishing pandemic winters and a triple-threat of viral waves returning last year, public health authorities are urging vigilance instead of alarm this holiday season.

“Really, this is what we had anticipated would happen,” said Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “We are not seeing or hearing any reports of hospitals running into capacity issues like we were last year, but we don’t feel we are out of the woods yet.”

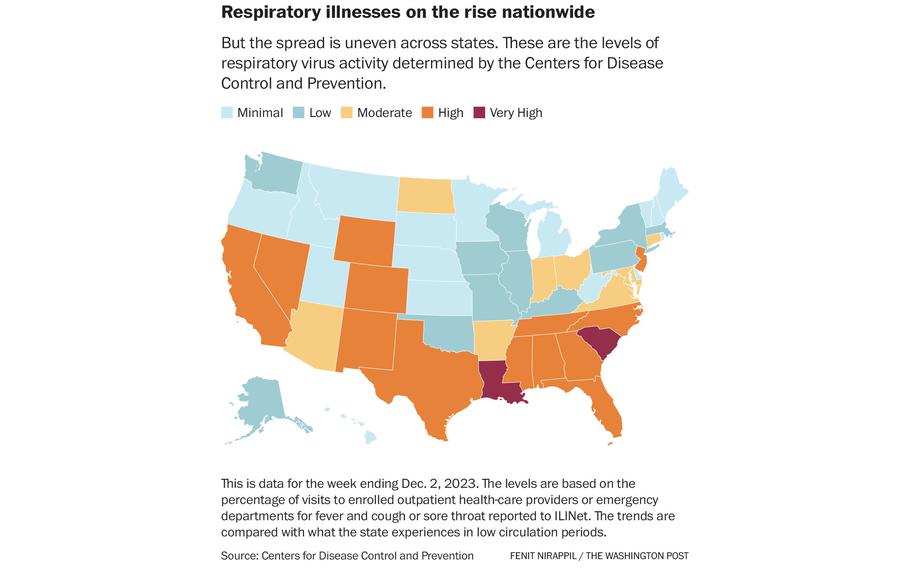

The toll of respiratory virus season is uneven across the country, cresting in some states and receding in others. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says levels of overall respiratory illness are high across most of the Sun Belt and in New York City and New Jersey, largely driven by flu and respiratory syncytial virus, widely known as RSV.

The spread is uneven across states. These are the levels of respiratory virus activity determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Fenit Nirappil/The Washington Post)

In Louisiana, designated by the CDC as one of two states experiencing very high respiratory illness, the primary driver is flu, which health officials say usually peaks this time of year. COVID is more unpredictable and is creeping up again just weeks after a fall surge waned.

“We can continue to expect periodic surges, and hopefully they continue to remain with relatively low clinical acuity,” said Joseph Kanter, Louisiana’s health officer. “Unless we get some variant that’s a real curveball, that seems to be the normal, and we are thankful for that.”

Children’s hospitals last year confronted a punishing wave of RSV, which can be dangerous for small children, especially infants, and some were overwhelmed. This year, RSV appears to have stabilized and peaked nationwide, though the season is just beginning in some states.

Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, a pediatric health-care system, has experienced a largely calm fall with RSV declining after an October peak and COVID circulating at low levels, although flu is on the rise.

“We are trending toward a more normal seasonal pattern overall,” said Andi L. Shane, a pediatric infectious-diseases specialist who is the system’s medical director for hospital epidemiology.

CDC Director Mandy Cohen urged Americans to get vaccinated, especially ahead of year-end holidays; to order free at-home coronavirus tests; and to adopt the usual precautions, including regular hand washing, opening windows for ventilation and wearing a mask.

“The number one way people can protect themselves proactively is vaccination, full stop,” Cohen said in an interview.

This is the first respiratory virus season in which some Americans can be immunized against all three major pathogens. For the first time, all newborns and adults older than 60 can receive RSV shots. An updated coronavirus vaccine targeting the latest variants is available.

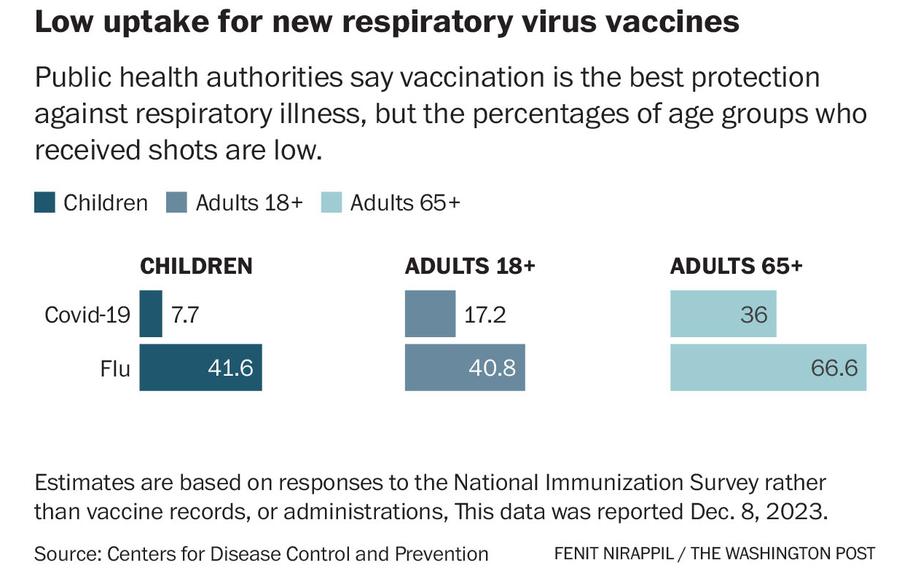

Yet vaccine uptake remains low. Based on surveys, the CDC estimates 8 percent of children, 17 percent of all adults and more than a third of seniors received the new coronavirus shot. About 16 percent of older adults received the RSV shot, while estimates are not available for young children. The flu shot remains most popular, with 40 percent of adults receiving it by December, the same as last year.

Health officials and experts offer varying explanations for the lack of uptake. There’s a shortage of monoclonal antibodies that act as a vaccine by preventing severe RSV disease in young children. The federal government no longer buys and distributes all coronavirus vaccines, meaning some doctors no longer stock them, and some pharmacies may not be part of certain insurance networks. And some Americans could just be tired of getting shots.

Public health authorities say vaccination is the best protection against respiratory illness, but the percentages of age groups who received shots are low. (Fenit Nirappil/The Washington Post)

The stakes are highest for older adults, the age group most susceptible to hospitalization and death from respiratory illness.

“Since the pandemic, there has been an increased attention on the need for older adults to get vaccinated at different times, at different schedules with different boosters,” said James McSpadden, senior policy adviser at AARP’s Public Policy Institute. “As a new vaccine rolls out, there could be some level of fatigue.”

Cohen, who is on a nationwide tour promoting vaccination, said many Americans haven’t incorporated a yearly COVID shot into their routines like they have an annual flu shot.

“We try to remind folks the virus has changed, and it continues to change,” Cohen said. “You want the updated vaccine to match what the changes in the virus are.”

The CDC is paying close attention to the JN.1 variant spreading quickly compared with other variants, suggesting it is more transmissible or better at evading immunity. It’s a closely related offshoot of the BA.2.86 variant that worried scientists because of an unusually large number of mutations that made it especially adept at bypassing immune protections.

Cohen said it is difficult to assess whether the COVID uptick reflects greater transmissibility of JN.1 or increased opportunities for exposure to viruses through holiday travel and indoor gatherings as cold weather descends in some parts of the United States. There is no evidence the latest variant poses a greater threat of serious illness or that the new vaccine is ineffective against it, Cohen said.

While health officials offer a largely reassuring portrait of a health-care system withstanding the rise of respiratory viruses, hospitals in some parts of the country are still experiencing strain.

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health, said the toll of the respiratory virus season should not be dismissed even if some trends have improved.

“The lesson we have yet to learn is how fragile our health-care system is,” Nuzzo said. “If you have to go to an emergency room on an average winter day, you may be waiting a long time because there’s a lot of other people trying to get care.”

Whitney Marvin, a pediatric intensive care specialist at the Medical University of South Carolina Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital, said this RSV season is the worst she can remember. Kids have stayed hospitalized longer than usual, and the season started later than it did last year.

This has placed extra strain on Marvin’s hospital because the RSV wave overlaps with the rise of other winter respiratory viruses. South Carolina is the second state designated by the CDC as experiencing very high respiratory illness activity. The hospital has had to coordinate with other hospitals in South Carolina, and even North Carolina, to divert patients.

“We’re still making sure patients are getting the care they need,” Marvin said. “It just may not always be at the closest hospital to them.”

Even though all infants are eligible for immunizations to prevent severe RSV disease, a shortage has forced the hospital to reserve doses for the sickest children. And many parents haven’t been able to get it at their pediatrician’s office either.

“The majority of people who want the vaccine have not been able to get it this year,” said Marvin, also an associate professor of pediatric critical care. “All of us in the ICU who see the sickest of the sick kids are all hopeful we can see a different RSV season next year with wider distribution of vaccine.”

A winter respiratory virus season is gaining ground ahead of the holidays. (Fenit Nirappil/The Washington Post)