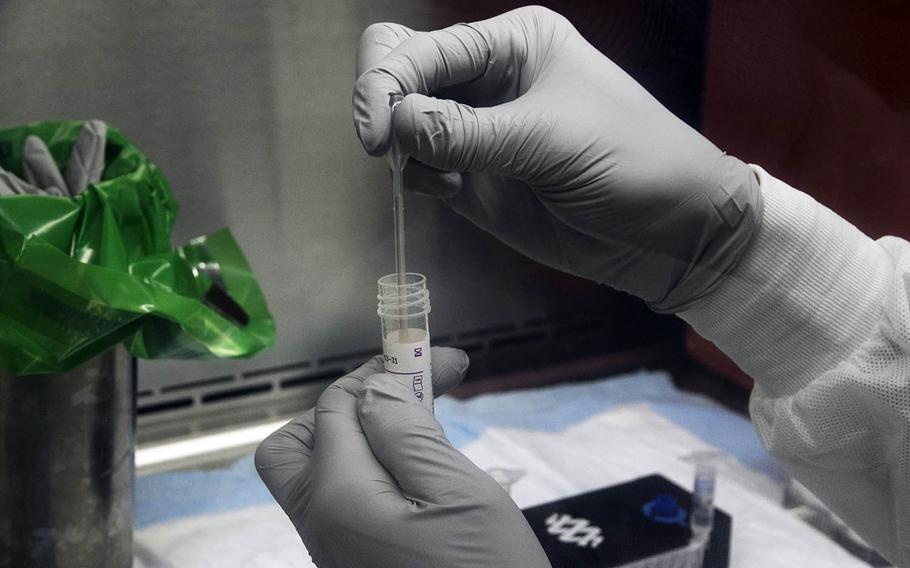

Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Anthony Ohlson, a hospitalman with the 3rd Medical Battalion, removes a DNA sample to be tested for the coronavirus at U.S. Naval Hospital Okinawa, Sept. 9, 2020. (Matt Burke/Stars and Stripes)

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See other free reports here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

CAMP FOSTER, Okinawa — Seaman Justin Funder remained focused on his phone and computer screen on a recent quiet morning inside the coronavirus response center at U.S. Naval Hospital Okinawa.

The 25-year-old hospitalman from St. Cloud, Minn., works in the COVID Cell, named for COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the coronavirus. At the start of the pandemic, cell members were responsible for all things, from fielding phone calls and taking down service member information to administering on-site tests and tracing the close contacts of those who tested positive.

As the spread peaked to hundreds of cases at U.S. bases on Okinawa over the summer, the number of personnel in the cell also multiplied. Funder was responsible for fewer tasks, but his days were much busier.

“I think at first it was frightening, but then it just became proper procedure,” he told Stars and Stripes in between phone calls Sept. 4. “We just knew that we had to do it.”

Today Funder still stands watch but breathes easier. As of Wednesday, the Marines had reported just four active coronavirus cases among its service members, civilian employees and family members on the island. The Corps last announced a new patient on Okinawa on Sept. 26.

Though the Marines admitted missteps battling the summer coronavirus wave, they say they’ve built infrastructure sufficient enough to effectively handle a winter spike if it occurs. They made slight adjustments to their procedures and “remain ready” to surge any effort to beat back the virus, wrote Maj. Kenneth Kunze, spokesman for Marine Corps Installations Pacific, in a Sept. 21 email response to questions from Stars and Stripes.

Funder said the U.S. military’s first responders are also ready.

“I feel like we have a very good handle on everything,” he said.

The pandemic had just reached the island when U.S. Naval Hospital Okinawa in March turned its annual disaster response exercise into one focused on the virus.

“We knew the impact a potential endemic could have,” the chief readiness officer for U.S. Naval Hospital Okinawa, Navy Cmdr. Jeffrey Ricks, told Stars and Stripes on Aug. 27.

Ricks is also deputy commander of Task Force Safeguard, launched by the III Marine Expeditionary Force in mid-July to align Marine Corps efforts to combat the virus across the Pacific.

“We ended up executing a pandemic drill for the hospital, focusing primarily on a large surge of patients,” he said.

At the same time, Ricks said, the hospital teamed up with III Marine Expeditionary Force, the 18th Wing and 18th Medical Group at Kadena Air Base and with Army and Navy units on the island. From that, the Joint COVID-19 Response Center was born.

Coordinated response The joint response center launched in April in a building behind the hospital at Camp Foster. It is one of four major organizations, along with the COVID Cell, Task Force Safeguard and Task Force Permanent Change of Station, created to combat the virus’ spread on Okinawa.

The center’s mission is to fuse all the contact tracing by all four service branches on the island, so planners know where to focus testing efforts, Marine Col. Eric Hamstra said. He is the officer in charge for the Joint COVID-19 Response Center and Task Force Safeguard’s commander.

The COVID Cell, in a detached building near the hospital, is an extension of the response center and is also home to the dispatchers for the Okinawa-wide COVID Care Line, a 24/7 coronavirus hotline.

The first call for anyone with coronavirus symptoms, or who believes they were exposed to the virus, is to the COVID Care Line. The caller is then forwarded to COVID Cell, where people like Funder arrange for testing at the hospital’s respiratory clinic or drive-through testing site.

The samples are sent to a naval hospital lab where Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Anthony Ohlson, 41, of Huntsville, Texas, a hospitalman from the 3rd Medical Battalion, opens the vials under a glass shield for DNA testing. Results are typically available in 45 minutes.

Samples from mass tests — of entire units, for example — are sent to South Korea for analysis.

The Joint COVID-19 Response Center is notified of positive tests, and COVID Cell contact tracers are dispatched to investigate any potential spread, Funder said.

Local officials on Okinawa are kept apprised with daily phone calls, Hamstra said.

If the person who tests positive arrived for a permanent change of station, Task Force PCS arranges their mandatory 14-day isolation period, also known as restriction of movement, Kunze wrote by email Sept. 14. U.S. Forces Japan requires all inbound personnel or those who travel outside Japan to quarantine for 14 days and test negative before exiting.

First infection The virus first hit Okinawa on Feb. 14 when a female taxi driver in her 60s tested positive, Okinawa prefectural officials said. By the end of April, the spread was held to 143 local cases and two airmen and a visiting relative at Kadena.

Then the virus appeared to vanish. Neither Okinawa prefecture nor the U.S. military reported any cases through May and June. Restrictions on U.S. personnel were eased, and life took a turn toward normal.

On July 1, the Marines at Camp McTureous reported their first positive test result. Six days later, personnel at Marine Corps Air Station Futenma were ordered to shelter in place after several people there tested positive. A day later, Camp Hansen went into lockdown to allow contact tracing and cleaning as more cases emerged.

As the number of infections grew daily by six to sometimes more than 12, the Marines raised the coronavirus risk level from moderate to substantial, or Health Protection Condition-Charlie, and reimposed restrictions on travel and off-base activities.

They also launched an “aggressive” test and trace policy, in which entire units and barracks were quarantined and tested, Marine spokesman Kunze wrote. The service also started taking temperatures around their installations and requiring entry logs for many buildings, along with individual contact-tracing logs, frequent hand washing and masks.

The Marines tested thousands of people, Kunze said, resulting in 362 positive results since July 1. At the two largest clusters, tests yielded 115 cases at MCAS Futenma and 169 at Camp Hansen.

Nearly two-thirds of all cases were asymptomatic, Kunze wrote. Only one person was hospitalized overnight as a precaution.

Ohlson, of the 3rd Medical Battalion, arrived at the hospital July 10 to begin analyzing test samples. Since then, he’s done close to 300 tests.

“During a peak eight-hour shift, I would have 30 samples,” he said as the analyzer hummed in the background. “It was pretty much nonstop.”

As the second wave intensified, alarms were raised over practices contributing to the spread.

Okinawa Gov. Denny Tamaki at a July 11 press conference voiced concerns over the military’s preparedness and demanded U.S. officials protect the general public from the virus spreading off base.

The Japanese defense minister at the time, Taro Kono, on July 14 pointed out that some newly arrived Marines and their families were serving their quarantine at an off-base hotel the U.S. military rented for that purpose.

On social media, reports flared that the clusters on MCAS Futenma and Camp Hansen erupted following beach parties and unauthorized trips to bars and nightclubs over Fourth of July weekend.

However, investigators could trace none of the cluster cases to parties, even by offering amnesty for information, Kunze wrote.

Instead, the Marine Corps took responsibility for the outbreak for permitting inbound personnel on the Unit Deployment Program to exit quarantine without being tested, provided they showed no symptoms. Mandatory exit testing was instituted in late July by U.S. Forces Japan.

Inbound personnel were quartered on Marine installations instead of the off-base hotel.

Kunze said fighting coronavirus took a massive logistics effort that improved over time, but it was “exceptional since the beginning.”

By Sept. 8, neither MCAS Futenma nor Hansen had any coronavirus patients, Kunze said.

“You don’t get to pick your war,” Hamstra said. “And you go to war with what you have at hand, and in that mindset, that the entire U.S. military has, we’re going to adapt and we’re going to win. I don’t think any of us would have anticipated this, but I guarantee every Marine out there is ready to excel in this situation.”

Stars and Stripes reporter Aya Ichihashi contributed to this report.

burke.matt@stripes.com Twitter: @MatthewMBurke1