Haitian-American children carry signs during a press conference in North Miami on March 5, 2024., as Haitian-American elected officials, faith and community leaders held an emergency press conference to bring awareness to the current situation in Haiti. (Jose A. Iglesias, Miami Herald/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — In the span of a month, Eliantes Jean Jacques has lost two family members to the ceaseless violence in Haiti.

In early February, gangs killed his brother. Two weeks ago, they murdered his cousin.

“There is no justice in Haiti,” said Jean Jacques, tearing up.

After the deaths of Jean Jacques’ relatives, the situation in his homeland has grown worsened. Since Friday, armed gangs have attacked the main airport, broken out hundreds of inmates from its largest prisons, killed police officers and declared their intention to overthrow Prime Minister Ariel Henry, who was out of the country on a diplomatic mission. Organized gangs now control most of the capital. About 15,000 people have been displaced in the most recent wave of violence, according to the United Nations.

And South Florida, the beating heart of the Haitian community in the United States, is hurting.

Jean Jacques, who hails from the coastal city of Port-Au-Paix and is living in Miami, is desperate to bring his brother’s children to the United States. But in recent days, he’s been unable to locate them.

“I don’t know where they are,” he said.

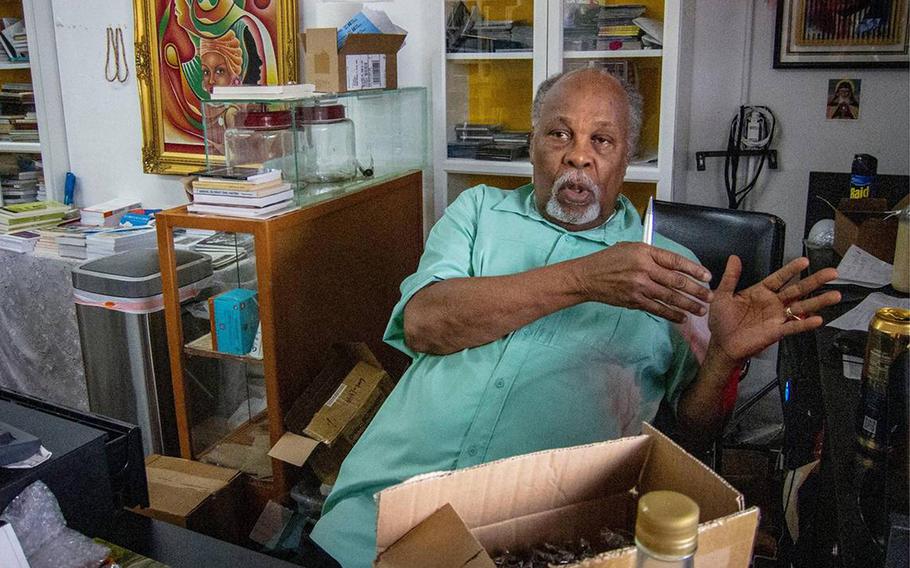

Eliantes Jean Jacques, who lost two family members to gang violence in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, speaks with a reporter inside a store in North Miami. (Jose A. Iglesias, Miami Herald/TNS)

Florida is home to more than 276,000 people born in Haiti. Hundreds of thousands of others in the state have roots on the island nation. On Tuesday, several Haitians and Haitian-Americans in Miami told the Miami Herald that they want Henry — a widely unpopular and unelected leader who rose to power after the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse — out of office. And they don’t want the U.S. government involved in the country’s turmoil. But a path forward for Haiti is uncertain amid the alliances of armed gangs leveraging the power vacuum to solidify control.

Above all, as Haiti approaches a total collapse of its political institutions, many people in South Florida feel frightened and helpless as family members at home try to stay safe from the chaos and violence.

“It was something that was boiling,” said Emmanuelle Elie, a 38-year-old woman from Port-Au-Prince. “I feel powerless. I don’t feel like I have a voice with what’s going on.”

Elie moved to the United States nearly three years ago while seeking medical treatment for her 4-year-old daughter, who is hard of hearing. She opted to stay in South Florida after an expansion of an immigration policy known as Temporary Protected Status in July 2021.

Elie, who lives in North Miami, is focused on helping her child here. But her parents, sisters and other immediate relatives still live in the country’s turbulent capital. Her father, an architect committed to preserving Haiti’s historical buildings, refuses to leave, she said. On Tuesday, she scoured social media and called her mother to see how her family was doing.

“They stay at home. They are used to this kind of situation, because when things like this happen, they organize themselves to have food and power,” she said.

Other Haitians told the Herald stories about their families trapped at homes amid the gang violence. Emmanuel Prophet who is from Croix-des- Bouquets, near Port-Au-Prince, still has cousins in Haiti. Prophet, who lives in Hialeah, said his relatives have stayed indoors hiding for months.

“It’s Haitians against Haitians,” he said, “They are fighting against themselves.”

On Tuesday the 67-year old Army veteran was browsing books with a Cuban-American friend at Libreri Mapou, a well-known bookstore in Little Haiti. Prophet has been in the United States for over 50 years, but his heritage run deep. He is grateful to be safe, but has found it difficult to witness the disarray from far away.

Relatives at home “can’t even open the door to get out,” he said. “I usually send food, but nothing is moving.”

Jan Mapou, owner of Libreri Mapou, talks about the situation in Haiti inside his shop in Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood. (Jose A. Iglesias, Miami Herald/TNS)

Jan Mapou, the owner of the bookstore, has a sister who teaches children in Port-Au-Prince. But her school has been closed since the fall. Her sister lives with her daughter, a national bank employee. Mapou, 81, said that his niece almost died in a kidnapping attempt on the way to work last month. He showed the Herald photos of a bullet hole that shattered her Jeep’s window.

“People are banging at their gate,” Mapou said.

‘It is time that they stop making decisions about us without us

At a media conference called by Haitian-American groups outside of North Miami’s City Hall on Tuesday evening, elected officials, community advocates, and service providers called for Haitian-led solutions to the country’s crisis. Children held up posters in the blue-and-red colors of the island nation’s flag.

“Let Haiti Live…Stop Abusing Haitians…Stop the Killing,” read the Creole- and English-language signs.

Miami-Dade County Commissioner and Family Action Network Movement founder Marleine Bastien denounced Henry’s leadership, the absence of elections since he became Haiti’s top official, and asked President Joe Biden’s administration to stop supporting his government.

She demanded that the U.S. government “stop all efforts to intervene in Haiti,” including the Kenyan support mission, and that it interrupt the flow of arms that fuel the gangs’ rampages, often shipped from Florida’s ports.

“The United States of America needs to listen to Haitian-Americans in Miami-Dade County and around the nation. We know the conditions there, from our own experience and from regular reports from friends and family there and meetings with civil society there,” said Bastien. “It is time that they stop making decisions about us without us.”

Among organizations at the media conference were Florida Rising, the NAACP, the Sant La Haitian Neighborhood Center, Komite Solidarite,the Haitian-American Foundation for Democracy and the Haitian American Democratic Club. There were several North Miami leaders, including Mayor Alix Desulme, City Clerk Vanessa Joseph, Councilman Scott Galvin, and Councilwoman Kassandra Timothe, and city council members from North Miami Beach, which also has a large Haitian population.

Not losing hope yet

Despite the dire situation, Haitians in Miami, some who left long ago looking for a better life elsewhere, spoke of the dreams they hold for stable governance and prosperity on the island, of a Haiti where all their countrymen can thrive.

Joseph, the North Miami city clerk, immigration attorney and daughter of immigrants, reminded other young people of Haitian descent that they are “still part of the Haitian nation” at the Tuesday media conference.

“We still have a duty to a homeland that gave us everything that we are,” she said, “Now is not the time to give up. Now is not the time to say that Haiti is gone because in fact it is not…Now is the time to wear that flag on your back. Remember where you came from. Where your ancestors came from.”

When Elie, the mother of the daughter with hearing loss, was living in Port-Au-Prince, she dreamed of using her legal education to help informal shop owners get the paperwork to make their businesses legal. In South Florida, she helps migrant families get the care and support they need for their children through her work at a nonprofit. She believes Haitians have the capacity to move their country forward.

“Without hope, it’s all lost,” she said. “If few people still have hope, they will find a solution.”

Frantz Fabien inside his shop, Fabien's Top Master, in Miami's Little Haiti. (Jose A. Iglesias/Miami Herald/TNS)

Frantz Fabien, a Little Haiti shop owner from the coastal town of Petit-Goâve, has run his store since 2006. Residents of the neighborhood come to him to buy everything from phone plans to new shoes. Haitian folk music overflowed from his business and into a busy intersection.

“I want peace and good governance,” he told the Herald of his aspirations for his homeland.

At his store on Tuesday, clients watched a Creole-language broadcast on a small television above the crammed walls of DVDs and kitchen appliances. Below scenes of Haiti was the phrase “Bagay yo konplike zanmim.”

The translation: “Things are complicated, my friend.”

©2024 Miami Herald.

Visit at miamiherald.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.