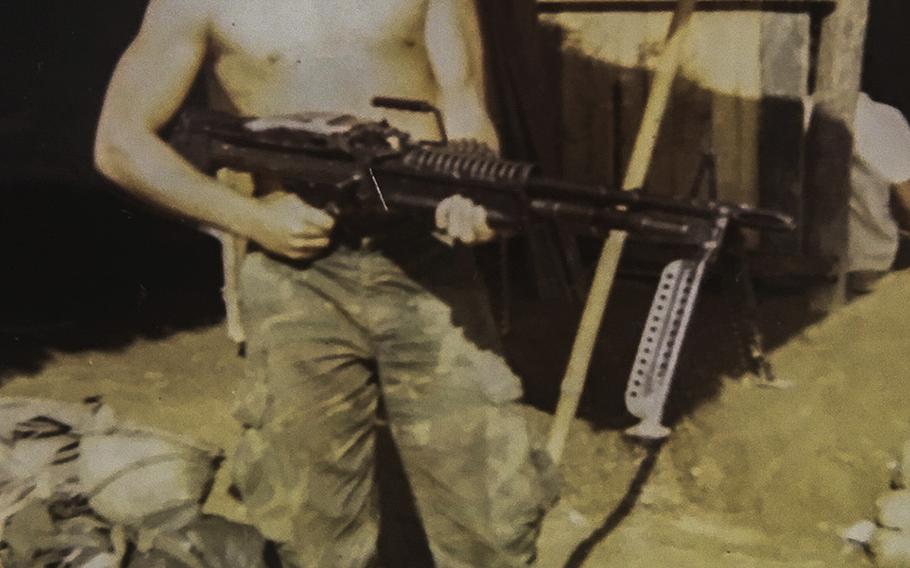

In this undated photo, Mike Sanzaro poses while deployed to Vietnam as a machine gunner. (Family photo)

WASHINGTON — There is a quality common among combat veterans, a quiet, unassuming nature that belies experiences few can match, let along understand.

Mike Sanzaro, a veteran of more than 300 combat patrols during the height of the Vietnam War, is soft-spoken and matter-of-fact, a man who speaks about extraordinary events in the way some would recount a trip to the grocery.

Perhaps that’s why it took the urging of Department of Veterans Affairs doctors for Sanzaro to request a Purple Heart that had been due him for more than 40 years.

In 1969, Sanzaro was a young man who spent his free time flipping through old issues of Leatherneck magazine. It was a lifelong dream, he said, to join the Marines – even though he had a comfortable life with a steady job as a movie theater manager and a girlfriend he planned to marry.

It didn’t take much for a Marine Corps recruiter to lure him away from all of that. “We can guarantee you a rifle,” Sanzaro was told.

“He lied to me. I got a machine gun instead.”

He went to boot camp in San Diego in July 1969 and soon found himself in Vietnam, working as an ammunition carrier for a seasoned machine gunner. When recounting the early days of his tour, Sanzaro mentioned that he single-handedly saved the lives of his entire squad.

His squad was on a routine patrol through the jungles about 15 miles west of Da Nang, when they were ambushed from the left. His squad leader formed them into a fighting line and ordered them to advance on the enemy position.

“We just walked slowly toward the enemy,” Sanzaro said. They laid down fire and received plenty in return. “You can hear those bullets go right by your head. I’ll never forget that feeling.”

As they fought, a group had circled around to the Marines’ left flank. The Viet Cong guerrillas – distinguished, Sanzaro said, from North Vietnamese Army troops by their poor accuracy – began firing right down their line.

“It was the worst situation you can think of,” Sanzaro said. “So, I just ran toward them.”

With bayonet affixed, he charged the bushes and cleared the ambush with a grenade and a full magazine’s worth of rounds. He had saved the lives of the men behind him, at great personal risk.

Afterward, no one said anything and Sanzaro believed he did nothing special.

“I’m being paid $214 a month to do that. So that’s what I did,” he said.

One of the sergeants whose life Sanzaro saved felt differently, and wrote him up for an award. It materialized more than a year later, as a Navy Achievement Medal awarded to him as he was preparing to exit the Marine Corps.

He almost didn’t get that chance.

If the events of Jan. 10, 1971 – nearly a year after that ambush – had gone slightly differently, Sanzaro’s life could’ve ended in a cornfield deep in the heart of Vietnam.

At that point, he was a hardened lance corporal and veteran of hundreds of combat patrols. He and a squad of eight other Marines from Company G, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, were on patrol near Fire Base LZ Baldy.

On that day, they spent most of the day trekking through the jungles “taking a few sniper rounds here and there.” But it was mostly quiet until the point man triggered a booby trap.

Their patrol was a small one, too small for a corpsman to be attached. So, the non-wounded – Sanzaro included – began to tend to the wounded as the radioman called for a medevac.

“As I was patching up this guy, I looked over and I could see a couple of trip wires,” Sanzaro said. They had walked into a kill zone of a half-dozen booby traps, marked with piles of rocks and other small, telltale signs.

Sanzaro ordered the squad to freeze as he picked his way to an old cornfield so that he could throw a smoke grenade to signal to the medevac pilot where it was safe to land.

“I knew they never booby-trapped areas where they grew food,” Sanzaro said.

A chopper drew near, prompting him and another Marine to grab the wounded man and carry him to the field. It wasn’t a medevac chopper, though.

Instead, it was a command chopper, carrying Maj. Cornelius Ram, Capt. Douglas Ford and Capt. Robert Tilley. They landed to provide medical assistance as best they could.

“As they’re walking, the point man’s feet fell off,” Sanzaro said. Badly shattered, they flopped toward the ground. “Even though he had a shot of morphine in him he gave out a bloodcurdling scream.”

Sanzaro squatted down to ease the stress on the man’s legs. That’s when Ram stepped on a land mine, estimated to be an 81mm mortar fashioned into a booby trap.

“The next thing I knew, some Marine had rolled me over and was trying to wake me up,” Sanzaro said.

“My entire helmet was split wide open. I thought, ‘I’m the luckiest son of a bitch in the world.’ Had that guy’s feet not fallen that split second, if I had not squatted down, that shrapnel from the booby trap would’ve cut me right in half.”

Ram was killed in the explosion. Ford was hit in the neck by shrapnel and died in Sanzaro’s arms as he attempted to get him to his command chopper.

Sanzaro and the other Marines managed to get the previously wounded Marines to the now-waiting chopper. Afterward, he took point for the remainder of the patrol and got his men back to the base.

“It was just my job,” he said. “I never expected anybody to pat me on the back.”

Nobody did.

He served the remainder of his tour in Vietnam and went home to southern California. He went back to his job, and picked up where he left off with his girlfriend. It was an easy transition in that regard, he said, but it was difficult in others.

“Everyone still talked about dates and all kinds of stuff like that. And here I am, I’ve experienced war and death … my mind-set was just totally different than everybody else I had left. It was kind of weird fitting back in. But I did.”

He missed the Marine Corps, and just a few years later rejoined, this time as an officer. He graduated The Basic School in 1977 and stayed on for five relatively quiet years.

He had put the war behind him — until March 10, 2010, when he suffered a heart attack. Doctors at the VA told him the heart attack was caused by exposure to Agent Orange. It also triggered dormant feelings of anxiety, anger and severe nightmares – all telltales signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“All the sudden Vietnam hit me like a ton of bricks,” Sanzaro said. “I was back for 40 years when it hit me.”

Eventually he sought help from the VA. He was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury and two decades-old cracks in his neck. The doctors determined that, like his resurgent PTSD, the injuries had remained hidden for more than 40 years.

They told him he rated a Purple Heart. The problem was, with four decades having gone by and no medical records of the event, he would have to find a witness. Sanzaro decided not to pursue the medal he deserved.

His daughter, Melissa Oldham, felt otherwise and tracked down Tilley, now a retired colonel. Tilley provided not only a statement but the official after-action report from 1971.

Even that paperwork wasn’t enough. The regulations required two witnesses.

“My daughter had tried, but she could not find anyone else. I thought the application for a Purple Heart was a dead issue,” he said.

That’s when two officers from Sanzaro’s TBS class got involved. Retired Col. John Rankin and retired Lt. Col. Paul LeBlanc joined the search. They found a member of Sanzaro’s squad, and after a couple of letters, the man provided the Navy Personnel Records office with a statement.

Rankin said Sanzaro’s story isn’t uncommon. Plenty of servicemembers have gone unrecognized for their efforts. “You don’t go out there and strive to earn a Purple Heart. It’s the circumstance that you’re dealt with that create the recognition,” Rankin said.

On June 28, 2017, Sanzaro received word that he would finally be awarded his Purple Heart. It will be pinned to his chest by retired Lt. Gen. Terry Robling in a ceremony in San Diego on Sept. 23, in front of other members of Sanzaro’s TBS class.

Sanzaro, now 66, said he was “totally overwhelmed” by the support he received from LeBlanc, Tilley and Rankin.

Overwhelmed, but not surprised. They were just doing their jobs – much like Sanzaro did many decades ago – as Marines.

“A fellow Marine asks you for something, you step up to the plate,” Rankin said. “You don’t ask a lot of questions. You see somebody that needs some assistance, you do what you’ve been trained to do.”