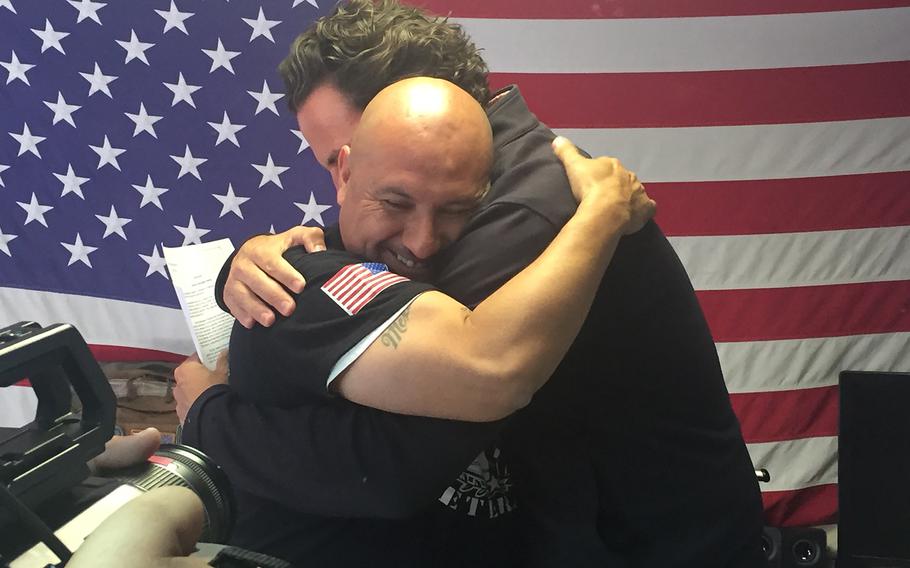

Deported Army veteran Hector Barajas-Varela hugs former state Assemblyman and Marine Nathan Fletcher on April 15, 2017 at the shelter for deported veterans in Tijuana, Mexico, after learning that he'd been pardoned by the California governor. (Courtesy of Hector Barajas-Varela)

Easter weekend came to Army veteran Hector Barajas-Varela with a gift – the kind he could hope for but hadn’t dared expect at the small shelter he runs for deported veterans in Tijuana, Mexico.

The California governor on Saturday pardoned Barajas-Varela and two other honorably discharged veterans who were deported from the United States after serving prison terms for criminal convictions.

The American Civil Liberties Union of California applauded the decision as historic and said it will likely clear the path for their return to the U.S. But the pardon comes with no promise. The final decision rests with U.S. immigration authorities.

For Barajas-Varela, 40, who has been on an emotional roller coaster since the U.S. government agreed to review his deportation status last year, the news was “huge.” He was deported in 2004 and, after returning illegally to the U.S., was banned for life in 2009.

He has been fighting to get back home ever since. Stars and Stripes featured Barajas-Varela and his efforts in 2016.

“It’s a glorious Easter weekend for myself and 2 other veterans that were pardoned and their families,” Barajas-Varela posted on his Facebook page. A video showed him in tears as he announced the news. “This is awesome.”

Born in Mexico, Barajas-Varela came to the United States illegally as a 7-year-old with his family, growing up in a tough neighborhood in Compton, outside Los Angeles. When he was old enough, he joined the Army, where he served with the 82nd Airborne from 1995-2001 and was honorably discharged.

After his service, he got into trouble. In July 2002, Barajas-Varela was convicted and sent to jail for an incident in which a weapon was fired from a vehicle, according to the pardon.

After completing his sentence in September 2004, he was detained by immigration authorities and ultimately deported. It turned out, he had never become a naturalized citizen, even though serving in the military had given him the right to apply for citizenship.

Military members are automatically granted the right to citizenship but they have to apply by filling out paperwork and taking tests. A report by the ACLU last summer said many servicemembers don’t always realize their naturalization is not automatic. Barajas-Varela said he thought he was a citizen until his arrest.

By his second deportation, Barajas-Varela had a young daughter -- an even more powerful pull to go home. Lilliana is now 11 and Barajas-Varela posts frequently on his Facebook page about his wish to be a present father for her. In 2013, he founded the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana for other veterans like himself, working to help them get jobs and find a place to stay.

He also explored options for getting home, conducting border protests and trying to draw attention to their plight. When the ACLU of California took on the issue, Barajas-Varela and others applied for reversals.

Barajas-Varela’s efforts – not just on his own behalf but for the community of veterans -- weren’t lost on California Gov. Jerry Brown. The governor issued 72 pardons Saturday -- an Easter tradition for him -- saying in a statement that “pardons are not granted unless they are earned.”

Of Barajas-Varela, Brown’s pardon stated: “Since his release from custody, he has lived an honest upright life, exhibited good moral character and conducted himself as a law abiding citizen.” The pardon cited Barajas-Varela’s service in the Army and his humanitarian service and good conduct medals and that he “established the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana, Mexico, to assist deportees in adjusting to life there.”

“Hector Barajas has paid his debt to society and earned a full and unconditional pardon,” the governor wrote.

Two other veterans, former Marines Marco Antonio Chavez and Erasmo Apodaca Mendizabal, received help through Barajas-Varela’s shelter to receive similar pardons.

“With these pardons, Gov. Brown has ended the life sentence of banishment these men have suffered every day since they were deported,” ACLU of California attorney Jennie Pasquarella said in a statement.

The three men had “long ago paid their price for their mistakes, but their deportation has been the worst price of all as they have been permanently separated from their families and the only country they knew,” she said.

Nathan Fletcher, a former California assemblyman who served 10 years in the Marines, joined the ACLU efforts last year as chairman of an advocacy coalition called “Honorably Discharged, Dishonorably Deported.” He met with the governor and presented the cases for pardons, pressing Brown on what he called the injustice of the deportations.

“When veterans lose their way we hold them accountable,” Fletcher said. “But it also shows they need help and we, as a grateful nation, should offer them a path to redemption. No one who is willing to die for this country should be deported. All they ask is to live out their days here, while being held accountable for what they did, like every other person who never served.”

When Fletcher learned Friday that three of the five deported veterans who had applied would be pardoned, he decided to drive to Tijuana to break the news to Barajas-Varela. He and a friend arrived at “the bunker” Saturday saying they were delivering some goods and sat around waiting for the governor’s announcement.

Barajas-Varela couldn’t help but wonder why they were coming to Mexico on Easter weekend. But as they kept looking at their phones, he started to get suspicious. By the time it was official, the deported veteran knew: “It was either really good news or really bad news.”

It’s been a long year for Barajas-Varela after he received word that the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services was reviewing his case. He met with immigration officials at the border in June to be fingerprinted, but was notified earlier this year that authorities were considering rejecting his case. He was urged to submit any additional arguments on his behalf. The pardon should have some effect – since the reason for his deportation has been removed. But it doesn’t guarantee a change in immigration status.

“It’s been up and down -- I’ve been feeling really depressed these last couple of months,” he said. “It’s hard work and it gets very intense. … Then all of a sudden all this work paid off. It feels really good. I finally got my reward.”

Barajas-Varela said he expects to hear from immigration authorities at the end of April. Pasquarella and Fletcher believe the pardons have paved the way for him to go home.

Even so, his mission will not be over. He has vowed to keep fighting for his deported brothers and sisters.

cahn.dianna@stripes.com Twitter: @DiannaCahn