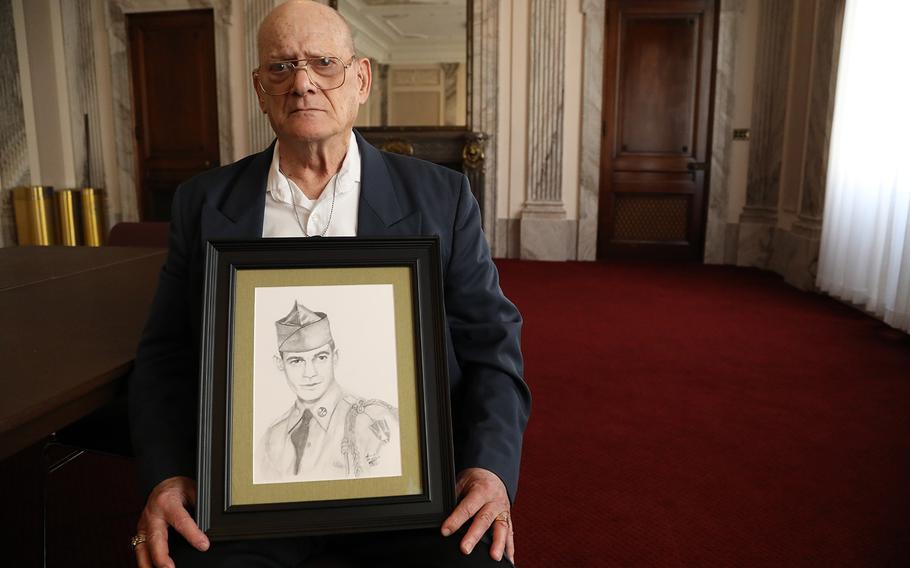

Clifton Sargent, holds a portrait of his brother Spc. 4 Donald Sargent, in a room at the Russell Senate Building March 15, 2019. (Caitlin M. Kenney/Stars and Stripes)

WASHINGTON — Four families connected by a single tragedy 57 years ago met for the first time to petition the government to fix a wrong: To finally add the names of 93 soldiers who died on a plane headed to Saigon to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall.

On March 16, 1962, Flying Tiger Line Flight 739 disappeared between Guam and the Philippines on its way to Saigon, Vietnam. Witnesses on an oil tanker claimed they saw the plane explode, but no trace of it was ever found, according to the Civil Aeronautics Board accident report.

On board the flight were 93 American soldiers, three South Vietnamese military men and 11 crewmembers. Their families say they were Rangers, and the accident report states the American soldiers were “mainly highly trained electronics and communications specialists.”

The war has been over more than 40 years, but the soldiers’ mission is still a mystery. The families have been unable to prove that that their loved ones were headed to the Vietnam-defined combat zone, one of the criteria to get a name placed on the Wall.

At the time, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported that the 93 soldiers on the flight were en route to Saigon, South Vietnam, to “relieve other American soldiers who have been helping train Vietnamese troops in the fight against Viet Cong guerrillas.”

Even so, there are strict requirements before names are placed on the memorial.

According to the nonprofit Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Department of Defense guidelines require that: a servicemember died within the defined combat zone of Vietnam; died while on a combat or combat-support mission to or from the defined combat zone of Vietnam; or died within 120 days from wounds, physical injuries or illnesses incurred or diagnosed in the defined combat zone.

Some of the families learned about the Flying Tiger flight — and one another — through websites and Facebook pages dedicated to the plane and its passengers. A day before the 57th anniversary of the plane’s disappearance, several family members were meeting each other for the first time, in an ornate room on Capitol Hill, waiting to speak to Congressional aides about their quest.

The families represent four men on the flight: Spc. 4 Donald Sargent of Maine, Sgt. 1st Class Melvin Hatt of Michigan, Sgt. 1st Class Raymond Myers of Arizona and Sgt. John Karibo of Ohio.

The niece of Sargent, Jennifer Kirk of South Portland, Maine, came with her 86-year-old father, Clifton Sargent, as well as her son, brother and mother.

Growing up, Kirk didn’t know what happened to her uncle because her grandmother, until her death, believed that he was coming home. No one was allowed to open or even touch his trunk.

“Fifty years later, I was able to get my dad and his sister to open the trunk to see if there were any papers, any note stating what their mission was, because we had nothing,” she said.

Kirk’s brother, named Donald after his uncle, contacted the office of Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and was able to get his uncle’s military records, and the family was able to learn about his military service but not about his last mission. Jennifer Kirk hoped by meeting with the other families, they could learn more about what happened to her uncle.

“It wasn’t right on how it was all presented. And how they were on this secret mission, and not being put on that Wall, because they went and they did what that mission was supposed to be,” she said.

“It’s not the soldiers' fault that the plane disappeared. Don’t even know why it blew up.”

She said she brought her family, especially her son, to Washington so they could fight together and keep the men’s legacy alive. She doesn’t want her uncle to be forgotten.

“The generation that we’re at now with my dad, they’re going to stop saying the name. We can’t stop saying their name,” she said. She believes in keeping their memory alive “so they don’t die twice.”

A name marks someone’s life — as the first thing they are given when they are born and the last reminder of their legacy when it’s etched into a headstone. The Vietnam Wall lists the dead and missing without rank, highlighting their names.

Over the next three days, these Flying Tiger families from across the country would be united by a passion to make sure their lost soldiers would be remembered forever.

On Capitol Hill Behind closed doors, the families told their stories to aides from several Senate offices. The daughter of Sgt. 1st Class Melvin Hatt, Donna Ellis Cornell, 62, brought folders bulging with documents for each senator on the Armed Services Committee, detailing what the families know.

She was the main force behind the meeting, petitioning senators for the second year in a row to have a full committee hearing to tell their stories directly to the senators.

She also suggested that if the Defense Department was unwilling to change the criteria for the Wall, Congress could pass a law, signed by the president, to exempt the Flying Tiger soldiers.

The decision to add a name is left to the DOD, not the Memorial Fund that oversees the Wall.

According to Jennifer Kirk, it was not until the senate aides heard the stories firsthand that they began to understand what was at stake. “Like, ‘I understand why you guys are fighting this fight.’ ”

Their reactions, she said, gave her “a little glimmer of hope.”

She would like to see something change while her father is alive, so he knows that it happened: “Couldn’t do that for my grandmother. Hopefully for my dad,” she said.

Her father said, “If this doesn’t happen, we’re all going to be feeling that we’ve been betrayed by our government.”

One of the Senate aides at the meeting was from the office of Sen. Gary Peters, D-Mich., the home state of Ellis Cornell.

“During the Vietnam War, our brave men and women were deployed thousands of miles from home in their service. The families of those who made the ultimate sacrifice have endured unimaginable pain and heartbreak,” Peters said in a statement to Stars and Stripes. “Unfortunately, for the families of those aboard Flying Tigers Line Flight 739/14, it is a pain that has not been properly recognized for too long.

“I will continue to work with these families and look for ways we can honor the servicemembers killed in the Flying Tigers crash,” he said.

Wall visit The Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall cuts into the Earth, its black stone walls engraved with more than 58,000 names.

As the Flying Tigers families entered the memorial, Kimberly Steinman-Elmquist, 57, pointed out a panel where there was “plenty of room” to put the names of their loved ones.

She is the daughter of Sgt. John Karibo, who died when she was only 20 months old. She was told by her mother that he had been trained in biological, chemical and radiological warfare.

This was 63-year-old Tommy Myers’ first visit to the memorial, something he said he has wanted to do for most of his life. He is the son of Sgt. 1st Class Raymond Myers and was told that his father was a supply sergeant in the Army. He later discovered that his father could speak five languages and had been stationed at Fort Huachuca, Ariz., a military electronics and communications equipment testing site going back to the mid-1950s. It is now home to the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence.

The experience of seeing the memorial “hurts and it helps,” Myers said.

“Now that I’m here, there’s only one thing missing, it’s the names of those 93 Rangers,” he said.

The group took a family portrait before the Wall, and as Steinman-Elmquist was saying that the Rangers and crew were looking down on them, the sun came out from behind the clouds.

“They’re all here,” she said.

Reading the names The group walked a short way to the Vietnam Women’s Memorial before sitting on a nearby bench. Surrounded by the other family members, Ellis Cornell read the names of the soldiers and crew of Flying Tiger Line Flight 739.

“May they rest in peace,” she said after reading the final name.

“And get on the Wall,” Robert Rogers added. The Vietnam veteran joined the families on their visit to Washington, bringing 93 personalized dog tags with him from California.

Final salute At Arlington National Cemetery there are headstones in memory of eight of the men who were on the flight, Ellis Cornell said. One of them was for her father. She found out the night before her visit that it had been placed by her grandmother.

“It’s pretty overwhelming,” she said of seeing the headstone for the first time.

Having family members of those who served with her father alongside her at the cemetery was also overwhelming, she said.

“We’ve been up until now connecting online and so on. And in a short amount of time we’ve become family,” Ellis Cornell said.

Rogers placed a penny on top of each headstone, signifying that someone had visited, and then saluted.

Hope in Congress On June 18, Sen. Gary Peters submitted a bill to Congress titled “Flying Tiger Flight 739 Act” that — if it becomes law — would allow the names of the 93 soldiers to be added to the Wall.