()

SAN ANTONIO — The military’s purpose is to kill, and it is well-prepared to carry out that mission. David Wood, a journalist with 35 years of experience reporting from wars across the globe, says the Pentagon and Department of Veterans Affairs are less prepared to teach troops how to reckon with that killing.

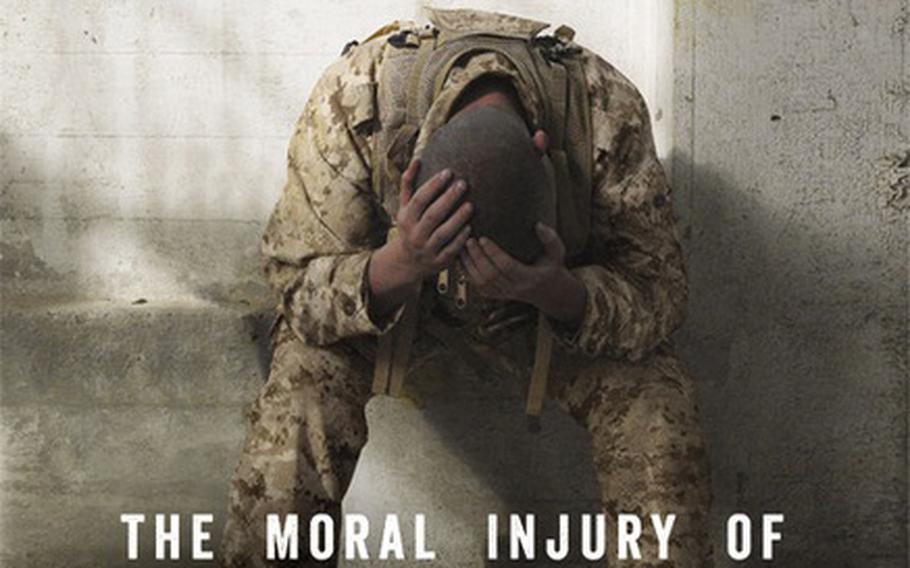

The consequence is moral injury, which Wood describes in the simplest sense as a violation to the code of what is right. The concept, distinct from post-traumatic stress disorder, has gained visibility in the wake of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to describe the feeling of veterans who say they left the battlefield with profound questions about the morality of their often split-second decisions.

Wood is the author of “What Have We Done,” published this month. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for reporting on severely wounded veterans for The Huffington Post. He sat down with Stars and Stripes to discuss moral injury and the future of its understanding and acceptance. The following transcript has been edited for length.

Question: Research is at odds to even conclude what trauma is – how to deal with it, treat it and predict post-traumatic stress disorder. Then you have moral injury, which is something else. What is it?

Answer: I came at this not as a scientist but as an observer of combat. What I’ve come to realize is PTSD and moral injury are two completely separate things, and I think everyone who goes to war comes back with some form of moral injury.

The simplest definition of moral injury is a violation of your sense of what’s right. We all walk around with a sense of what’s right. We absorb it as infants, we learn it as kids.

Then in the military you learn moral values on top of that — duty, honor; you take care of your buddy no matter what. Very strong moral principles. Those are really the best of what we have as a country. Those are our highest ideals, and we send people to war armed with those ideals.

The problem is, in war you can’t possibly live up to those ideals. ... In my experience, people we send to war struggle with what they see and do, what they have done to them. And that’s moral injury.

They come back, and they’re not sick, they’re not disabled, they’re not the insulting stereotype of the homeless, drug-crazed veteran. But they’re not OK.

Q: Moral injury was coined in the ‘90s by researcher Dr. Jonathan Shay, but the term has taken off in recent years as something distinct and clear from PTSD. Is there an inflection point between combat operations winding down and time for reflection for these things to spill out of people?

A: That’s probably true. I also think these wars in Iraq and Afghanistan made people more susceptible to moral injury than we realized. There are a number of things about Iraq and Afghanistan that are more morally perilous than past wars.

Most people were married that we sent into war zones, more than in the past for instance. So here you start with a moral injury by saying to your spouse and kids, ‘I’m going away and it’s more important than being with you’ and there’s a moral injury on both sides there.

And unlike all of our past wars, the United States didn’t send people to Iraq and Afghanistan to win in a military sense. We sent them there to help.

As President (George W.) Bush said during the Iraq War, ‘As they stand up we’ll stand down.’ That was the whole deal. It wasn’t to kill them all and come home. It was to establish a working democracy. But we didn’t. I know a lot of people who came home very proud and with an enduring love with the people they served with. But, overall, it wasn’t good. We didn’t really help them. And people went over and over again. And those things drove moral injury deeper and deeper.

Q: In past conflicts there was a divide between senior commanders and junior troops, where those commanders would order men and women into battle. It was top down. But in a counterinsurgency, you’re doing missions like providing electricity or making sure local police are getting paid. So there has been a shift of moral decisions made by superiors to junior troops. How has shifting that burden impacted moral injury?

A: I saw this over and over again, not only in situations where there was a tactical situation like a firefight when someone had to decide if that person was a target, where you had to make an immediate judgment. ...

In these wars, we have thrust people into situations where there is no clear moral or tactical answer.

The role of civilians has really morphed into something unrecognizable from past wars, where we had very clear definitions of a combatant and a clear distinction from a noncombatant. Now you have a schoolkid who is paid a dollar to drop an IED in a hole on his way to school. Is he a combatant or not?

I’ve seen lawyers from the International Committee of the Red Cross, which oversees the Geneva Convention, tie themselves in knots trying to define a civilian. That’s why we have lawyers in Geneva discussing these weighty matters of war.

But you also have 20-year old riflemen out there who have to make snap decisions and asking themselves, ‘Do I err on the side of killing a civilian and protect my buddies or not?’ The thing I keep coming back to is the highest of all military values: You’re responsible for your buddy no matter what. Does that mean killing a civilian? Yeah, it does. Accomplish the mission. But it’s a moral injury when you come back.

I wrote about a Marine who found himself in a situation where he was killing a 12- or 13-year old kid. Tactically justifiable. Legally justifiable. Morally justifiable. All good to go. But he killed a child. That’s not OK.

Q: Dr. Brett Litz, a moral injury researcher, has said moral injury at the Defense Department and VA is “significantly unaddressed.” Some people might say training on moral injury should be included in basic training, along with how to apply a tourniquet or assemble an M16 rifle. What is stopping the Pentagon and VA in deciding this should be part of training, doctrine and culture?

A: The Marine Corps has begun this process by recognizing mental health injuries are actual combat wounds. So that’s a first step in realizing we’re talking about people who could be put into a situation where they have to take an action that violates their sense of what’s right. That it’s a wound that can be treated. So that’s a huge first step.

Is there a way to prepare people for the kind of things that may happen when you go to war? Turns out there are ways. There is role playing.

There was a program I saw a couple years ago – a video program with an avatar. It was training people to recognize that you may get into morally difficult situations. You may find yourself killing civilians in a justifiable way, but how are you going to think about that?

I think that’s very valuable because most people, including me, went to war without knowing there was such a thing as moral injury. Then when you come face to face with it, you don’t know what to do. ...

When you have a whole generation of veterans who don’t want to talk about what happened, that’s not healthy for them. Or us. And “us” is an important piece of it.

Recognizing moral injury as a wound leads us to helping. As you point out with PTSD therapy, it hasn’t been that effective, but there is some interesting research going on with how we might help out.

As many ancient societies knew, if you can find a way to have a formal ceremony or process to recognize something bad happened, that there is no blame attached and that we love you anyway, that we accept you anyway, I think that’s the way forward. Dr. Brett Litz and other people are working to put that process into a therapeutic framework.

There have been promising experiments using a process where a person with a moral injurious experience can stand in front of a group of peers and say, “I did this terrible thing and feel horrible.” And to have her peers say “That is bad, but we accept you as a human being, and that doesn’t define who you are.” I think that kind of approach can be really helpful.

Q: There is tension in our culture about who veterans are and what they have done. One side is the heroic, indestructible veteran. And the other is the victim suffering from unending trauma. Those sides are simplistic, and moral injury is complex. Is there a way to bridge that as a culture?

A: I’ve been trying to get us civilians to try to get veterans to discuss their experience. It would be great if the VA came up with a miracle therapy for moral injury. But I don’t think veterans will be healed until they feel most Americans understand what they went through and can walk among them.

There is a movement of church and civic groups who have decided to get to know veterans. I keep running into people gathering civilians and veterans together to begin talking. And that is so healthy. And so awkward and difficult.

I think there’s a dawning among civilians that veteran stereotypes are false. And a growing awareness that most people come back from war with their values violated. So my mission is to encourage people to ask.

Q: The Pentagon and the military often take the shape of the administration. Where do you see the progress of moral injury as an idea under a Trump administration?

A: I think the single most important change a new administration can make is to recognize and acknowledge the purpose of the military is to kill. We know killing imposes a psychological burden on the killer. It’s beyond dispute. Even in combat when it’s legally and morally justified, people are twice as likely to develop mental problems than people who did not kill.

And we don’t talk about that. The Defense Department hardly uses the word “kill.” When a daughter is talking about her father in the military, she doesn’t say, “He signed up to kill.” You don’t see it in recruiting commercials.

I doubt the new administration will do this, but it would be helpful if they said, “The military kills and should do it only if we have to, and if you sign up, that’s what will happen.” I think that would clear up a lot of moral confusion.

Q: What direction is moral injury heading, in regards to understanding and acceptance?

A: There’s a guy at West Point -- Peter Kilner -- who developed a teaching module on killing. His realization was that we send people to kill but we don’t teach them how to think about it. The module teaches the difference between justifiable killing and murder. My understanding is that it was too controversial.

But the idea is out there. We need to teach people sent to kill about how to think of the morality, so you’re not screwed up when you get there and all you can think about is, “Thou shalt not kill.”

We can have different ideas on the morality of killing. And that is fine. But if we as a country send people to kill, we need to teach them how to think about it.

Horton.Alex@Stripes.com Twitter: @AlexHortonTX