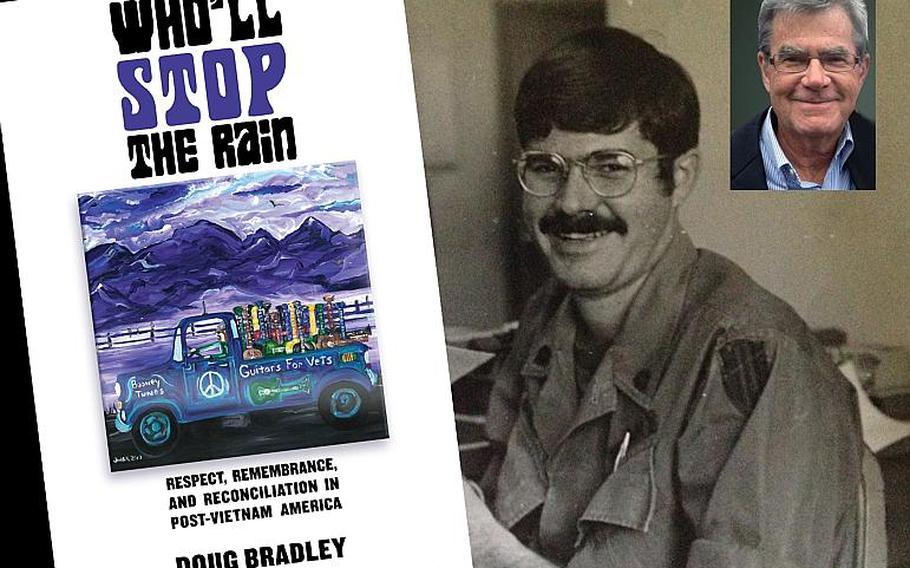

"Who'll Stop the Rain: Respect, Remembrance, and Left: Reconciliation in Post-Vietnam America," is author Doug Bradley's testament to the power of "call and response" in unburdening Vietnam veterans. Center: Bradley in Vietnam, 1971; Right: Bradley today. ()

Long as I remember / the rain been comin’ down

Clouds of mystery pourin’ / confusion on the ground

Good men through the ages / tryin’ to find the sun

And I wonder, still I wonder / who’ll stop the rain

Fifty years ago this week, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Who’ll Stop the Rain” peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100. CCR lasted only two more years, but the song resonates to this day. It also provided an apt title to the latest book by Doug Bradley, a Vietnam veteran who has written extensively about his experiences during and after the war.

Among his other works, Bradley co-authored, with Craig Werner, “We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War.” The critically acclaimed work, named best music book of 2015 by Rolling Stone, explores how U.S. troops used music to cope with the complexities of the war in country and upon their return to the States.

(Spoiler alert: This review is a recommendation. If you’re inclined to read “Who’ll Stop the Rain” and you consider yourself a music fan, do yourself a favor and order “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” at the same time.)

“Who’ll Stop the Rain: Respect, Remembrance, and Reconciliation in Post-Vietnam America,” released in paperback March 10, is the flip side to “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” Really, though, the closely related books are more like a double A-side, akin to the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.”

“Who’ll Stop the Rain” digs deeper into the post-Vietnam experience. Music is, of course, a major player. Movies, monuments and memories also frame the ways veterans and non-veterans wrestle with the war’s legacy. Women’s voices, often overlooked elsewhere, figure prominently in Bradley’s book. Two more unsung heroes, public radio and television, are lauded for their roles in helping to archive veterans’ private memories as a means of creating a fuller, more accurate public memory of the war.

During their monthslong tour for “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” Bradley and Werner tailored their presentations by playing Vietnam-era musical selections related to the particular location or region. Bradley wrote this follow-up to share experiences gleaned from those presentations and to bear witness to the power of call and response as a means for unburdening and healing.

For those unfamiliar with call and response, which has deep roots in African-American culture and music, an example would be a preacher asking his congregation, “Can I get an amen?” and receiving said amen in return. Musically, the Staple Singers’ “I’ll Take You There” is a notable example from the ’60s.

Bradley’s well-organized book is broken down into five main sections:

Sonata, “I’ll Take You There,” documents the calls and responses witnessed during the tour for “We Gotta Get Out of This Place”; Counterpoint, “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” examines the public memory of Vietnam, and how that memory often contradicts the war as it was experienced by veterans; Adagio, “Blame It on My Youth,” explores the lingering effects of guilt, shame and bitterness and the debilitating effects they can have on veterans and non-veterans alike; Rondo, “Time to Lay It Down,” shows how Vietnam veterans are helping each other and their communities transform through a variety of therapeutic activities; and Da Capo, “Who’ll Stop the Rain?” presents diverse veteran voices and suggests strategies for reconciling the divisiveness of Vietnam and bringing veterans home.

Bradley knows the subject like crate diggers know forgotten B-sides. For starters, he was there. Stationed in “the air-conditioned jungle,” aka headquarters at Long Binh, he was an Army journalist during his 1970-71 tour. Upon returning home and relocating from Pennsylvania to Madison, Wis., Bradley helped establish the community-based service center Vets House. And he’s a lifelong music fan. The songs were a part of his Vietnam experience as well. They helped him heal when he came home. He also returned home through writing, which ultimately led to his collaboration and a co-taught class with Werner at the University of Wisconsin. They always ended the semester, incidentally, by playing CCR’s “Who’ll Stop the Rain.”

Bradley describes early in his “Who’ll Stop the Rain” the “Memphis epiphany” he experienced when he and Werner presented their book just after its release at The Stax Museum of American Soul Music on Veterans Day 2015. Their decision to structure their presentations around call and response had already paid a few early dividends, as the responses brought on by attendees’ connections to the selections led to recollections and conversations that took place in nonjudgmental settings. At Stax, an affecting affirmation surfaced.

On that particular night in Memphis, in that hallowed hall of soul music, a veteran broke the uncomfortable silence after the presentation by spontaneously breaking into the soul classic “I Stand Accused” and giving all in attendance a spine-tingling taste of music’s power to heal.

“All of us — authors, audience, and probably the ghost of Isaac Hayes, who’d recorded that song for Stax — were hooked, united in that moment as Henry, now momentarily back in Vietnam almost 50 years earlier, was channeling his loneliness, confusion, and heartache through the song,” Bradley writes.

That spontaneous response itself became a call that elicited more responses from those in attendance. It was a scene Bradley observed over and over again as he and Werner took their book around the country for more than two years.

Bradley makes a strong case for listening as the key to understanding the war and bringing its veterans home. He wisely chose to carry over a key element from “We Gotta Get Out of This Place”: first-person veteran “solos” that complement the narrative. Bradley also makes a compelling argument that veteran voices add up to a more accurate record of the war than the Hollywood films that have created a flawed memory in the American consciousness.

One of the most amusing — and frustrating — anecdotes in the book is Bradley’s account of following “Apocalypse Now” director Francis Ford Coppola around Madison, peppering the auteur with pointed questions about inaccuracies in his Vietnam opus. After several press stops of unabated public badgering, Coppola finally engaged. Bradley found his answers less than satisfying.

The author believes Hollywood did a much better job with its movie soundtracks, and provides ample evidence to support the assertion. CCR is one of the soundtrack bands that figures most prominently in the public memory of the war. The group is an obvious touchstone for the book, as it is for Vietnam veterans. As Bradley and Werner discovered in their research for “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” CCR was a band so popular with the troops that it could bridge racial divides in Vietnam. When there was otherwise no common ground, everyone could agree on Creedence.

There are several other reasons for Creedence’s strong association with the war. They were at the height of their popularity during the Vietnam era. Two of its four members served in reserve units. Their music was, unfortunately, readily available for movie and TV soundtracks because of a bad record deal. The band’s music also is rich in American traditions such as the blues — and call and response. CCR frontman John Fogerty had an ability to pointedly criticize the war machine while just as unabashedly supporting the troops. He also was able to tap into universal themes and ask big questions.

The song that provides this book’s title poses a query that has yet to be answered, its call hanging in the air like the E minor chord that hangs over the “who’ll” at the end of each verse. The answer, my friend, to paraphrase another notable ’60s songwriter, is, well, you know the rest. The recent peace agreement in Afghanistan paved the way for an end to America’s longest war and gave the question new relevance.

“Too many Vietnam veterans have yet to make it home, and we can’t afford to repeat the same mistake with this generation of men and women veterans,” Bradley writes. “Listening to their voices, reading their stories, and helping them to express their experiences may just be the best way to bring them back, to help them lay it down.”

Bradley has issued his call. How will we respond?