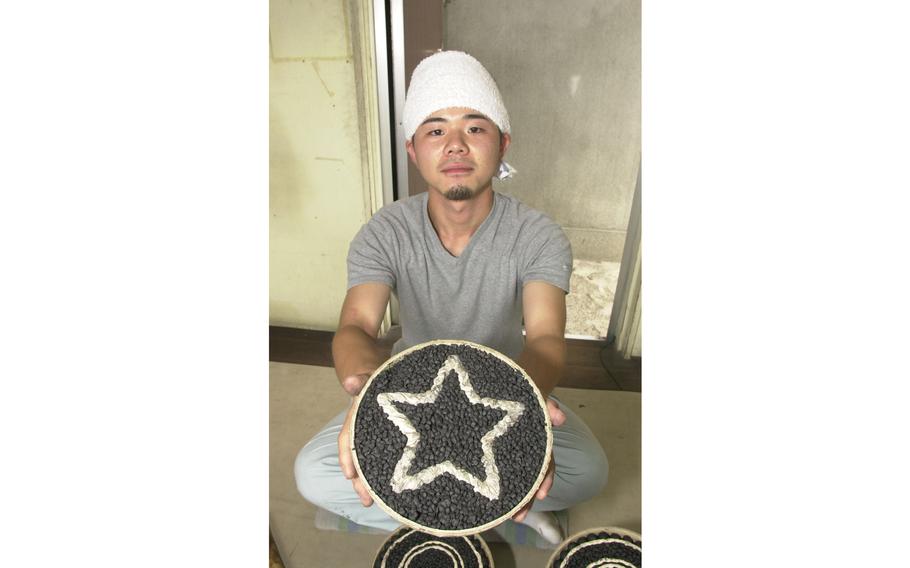

Toshikazu Kosuge shows the inside of a firework that blows up into a star pattern. (Jim Schulz/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in Stars and Stripes’ Sunday Magazine, July 20, 2003. It is republished unedited in its original form.

Fire Art Kanagawa spends eight months putting together their products with extreme precision.

All that effort culminates with a loud bang and bright lights, as the same folks who put together Fire Art’s fireworks light the fuse and wait for the explosion.

The payoff: claps and cheers from the thousands to millions of people who’ve come for the show.

Located in Atsugi city in Kanagawa prefecture, near Atsugi Naval Air Facility and the Army’s Camp Zama, Fire Art Kanagawa is one of many factories in Japan that produce and display fireworks for some of Japan’s many summer festivals.

Hanabi (fireworks) craftsman roll the balls of firworks to make sure they are tight and have a good seal. (Jim Schulz/Stars and Stripes)

Fireworks are a summer staple in Japan. Hundreds of firework festivals are held throughout July and August.

Despite the increasing number of imported fireworks, which are cheaper in cost, Fire Art Kanagawa, with just 15 full-time employees, engages in fireworks production from scratch to “bang!”

At the factory, “hanabi-shi” — or the fireworks craftsmen — started producing fireworks in October. The process starts by mixing explosive chemicals which are then put into pots and stirred while pouring water in to make them into small balls. If a different chemical is added while the pot is being stirred, it creates explosives that change colors.

These round explosives, called “hoshi” — which literally translates to “stars” — are the ones you see when the fireworks explode.

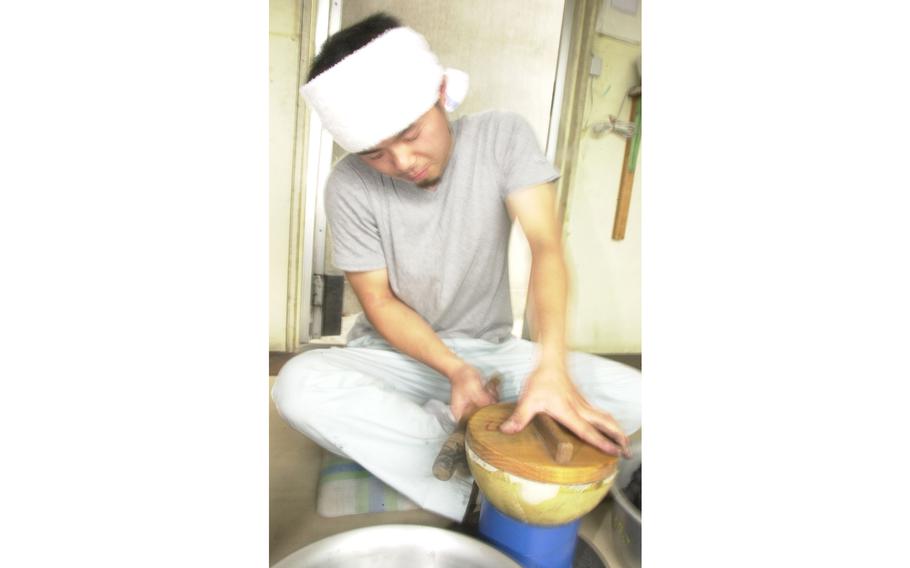

Toshikazu Kosuge taps the outside shell of the firework to settle the black powder balls into place, forming a tight fit. (Jim Schulz/Stars and Stripes)

Hanabi-shi then lay the explosives in a half sphere paper container. The explosives need to be laid without a gap, so that when the fireworks explode, there is a perfect sphere. After a layer of explosives is lined along the side of the bowl, a tissue-like paper is used as a divider. Gunpowder, used to spatter hoshi when fireworks explode, is packed. The process is repeated depending on the size and design of the fireworks.

But this is only half the process. For it to be complete, the two semispherical bowls need to be put together.

“The key when putting them together is to balance out the explosives at the joint,” said Hitoshi Okawauchi, a hanabi-shi. If no explosives overlapped at the joint, the fireworks will not be a sphere but will have a line of empty space, he says.

After two parts are joined, paper is glued outside to hold the containers together. After they are glued, they are dried in the sun and then more papers are added until they are firm enough that they would not fall apart in the air but not too firm so it will explode when the gunpowder is lit.

Fire Art Kanagawa makes various sizes of fireworks ranging from 2.3 inches in diameter to 26.3 inches. For a 12-inch explosive, it is shot up 1,150 feet in the air in seven seconds and explodes 984 feet in diameter in just 2 seconds. The most common fireworks are spherical, so they look the same from any angle when they explode. Even as a 22-year veteran, Okawauchi said every time fireworks are lit up, he prays for it to “successfully explode.”

“It feels so good when I hear cheers from the audience when the fireworks are shot,” he said. He says this has kept him in the job although some days can be long and hard.

On the day of a major waterside fireworks festival, they leave at 5:30 a.m., get on a boat around 8:30 a.m. and stay out on the water until 9 or 10 p.m. During their busiest seasons, they keep this schedule every weekend — or sometimes three times a week.

“It is exciting to be able to engage in something from scratch to the finish,” says Toshikazu Kosuge, a hanabi-shi at Fire Art Kanagawa. “I don’t consider my work finished until cleaning after the fireworks.”