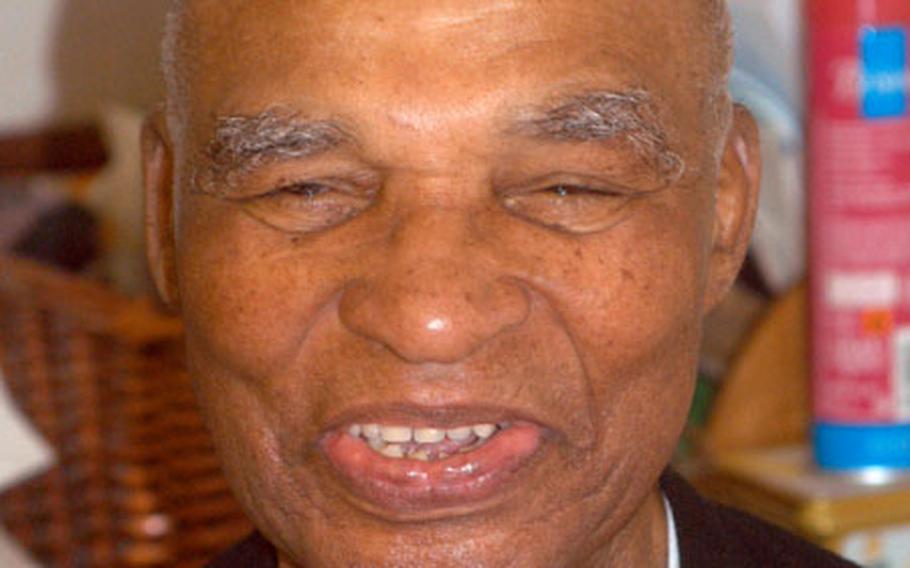

Purnell Sterrett, 83, is a veteran of America's segregated military, which gradually ended after President Truman ordered the services to desegregate. Below is a photo Sterrett taken during his time in the U.S. Army Air Corps. (Ron Jensen / S&S)

“In a completely integrated unit where you’d have white soldiers, particularly from southern states, serving under [black] noncommissioned officers or officers … I think you would have a problem definitely.”

— Gen. Omar Bradley, 1949

Purnell Sterrett’s first attempt to join America’s military was a bust.

In the years before World War II, the Navy he longed to enter had limited jobs for people like him. Black men, he was told, could serve the Navy only as cooks or bakers.

“I said, ‘If I wanted to learn how to cook or bake, my grandmother could teach me,’ ” recalled Sterrett, who wanted to be a gunner’s mate. “(The recruiter) took my application and dropped it in the trash can.”

Fast forward a few decades, and the military that treated Sterrett like an unwelcome guest is considered a colorblind institution, offering opportunities for anyone regardless of race, ethnicity or religion. Black generals and admirals have lost their newsworthiness, as have top black noncommissioned officers.

“The military has done so well,” said John Sibley Butler, a sociology professor at the University of Texas in Austin and an author of books about race relations in the military, “you don’t even think about it.”

In his writing, including the book he co-authored called “All That We Can Be: Black Leadership and Racial Integration the Army Way,” Butler has praised the military as a place of equality and opportunity, citing the overall mission as the impetus.

“The purpose of the military is to defend the country,” he said in a telephone interview. That’s too important a task to do while worrying about the color of the person standing next to you, he said. The need to accomplish the mission outweighs everything else.

Sterrett, 83, remembers a different time.

Educated in a segregated school on the outskirts of Baltimore, Md., he dropped out after eighth grade.

While he could sit wherever he pleased on the city’s public transportation, many of the city’s restaurants would not admit him.

Baltimore’s streets were often filled with sailors, especially when the fleet docked in the city’s harbor. Less than 50 miles to the south was the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis.

“I always had an urge to see what the Navy was like,” Sterrett said.

His first attempt was unsuccessful because he wouldn’t knuckle under to the limitations. But after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered more jobs opened to blacks as America went to war.

Sterrett, who now lives in Beck Row, England, near RAF Mildenhall, applied again and was accepted. But the Navy would not use its training bases to train black sailors, and Sterrett was forced to wait again. Camp Robert Small eventually was opened as an annex to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago.

Sterrett was trained as a munitions expert and shipped out in December 1942 to Navy Advance Base 140 on the island of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides Island off the east coast of Australia. The fleet visited the island to replenish its ammunition supply.

After the war, Sterrett returned to the United States and left the Navy in January 1946. Two months later, unable to find work in the civilian world, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, the forerunner to the U.S. Air Force.

His munitions background placed him in the 7281st Air Ammunition Squadron, which was sent to Europe to clean up ammunition that had been left behind as the front moved across Germany during the war.

Sterrett displays a photo of the unit taken before it shipped out. The only white faces belong to the officers seated down front. Sterrett said that was normal then.

Change was coming, however. President Truman was hearing stories of the poor treatment of America’s black war veterans. Walter White, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, especially, had told the president of black veterans being abused. Their war service had done nothing to change the racist attitudes they endured before the war.

Among the collection of paperwork from Sterrett’s military career is a printed letter of appreciation from Truman given to all war veterans. It says, in part, “[W]e now look to you for leadership and example in further exalting our country in peace.”

But the president’s words did not represent reality.

Stationed in Texas in 1946, Sterrett and other black soldiers were asked to move to the back of the bus taking troops into San Antonio.

Sterrett, still a bit amazed at the experience, said, “I just came from four years in the Pacific [during the war] and he’s asking me to get in the back of the bus.”

Ray Geselbracht, special assistant to the director of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Museum and Library in Independence, Mo., said Truman had earlier established a civil rights commission, something no president before had even considered. One recommendation was ending segregation in the armed forces.

“It was clear to Truman and his advisers that Congress would not support such a thing,” Geselbracht said in a telephone interview.

So on July 26, 1948, Truman signed Executive Order 9981, bypassing Congress as he brought integration to the military.

“It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religious or national origin,” the order declared.

The military was to desegregate “as rapidly as possible,” the commander-in-chief demanded.

The order didn’t sit well with the military’s brass. Gen. Omar Bradley, a World War II war hero, declared racial equality should come to the military only when it existed in the rest of society.

Kenneth Royall, secretary of the Army, said his service was “not an instrument for social evolution.”

But eventually, boosted by the need for manpower in the Korean War, integration took hold.

Sterrett first experienced the integrated Army in June 1950.

“We were the first unit in Germany to desegregate,” he recalled. “They sent us two white guys. One was from Florida and one was from Indiana.”

Their names were Russell and Jones, Sterrett said, and “overnight” they became just two guys in the unit. No fights. No problems.

Sterrett saw more changes. The military was promoting blacks and giving them responsibility once out of the question.

In the late 1950s, he was working at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, and, he said, was the top enlisted airman in charge of the nuclear weapons stored there.

“This was a showplace. All the distinguished visitors that came to Ramstein, one thing they wanted to see was the special weapons area,” he said.

When the visitors — members of Congress, top military brass and the like — reached the gate, Sterrett was called to escort them on their tour. His appearance, he said, never failed to shock them.

“You should have seen the look on their faces,” he said. “They tried to look like it didn’t surprise them, but I could tell. It surprised them. They couldn’t believe it.”

Sterrett retired in 1965 while serving at RAF Bentwaters in England. He married a British woman and found a job on the local economy.

He later worked for years at RAF Mildenhall and RAF Lakenheath in several capacities. He’s fully retired now, but lives a stone’s throw from RAF Mildenhall, where black officers and black NCOs are as common as foggy winter mornings.

Sterrett doesn’t mind that black military members may take for granted the opportunities they have. These are different times — better times — especially in the military, where opportunities extend beyond being a cook or a baker.

“It’s changed a lot now, but, still, you can do more in the military than you can in the civilian world,” he said.