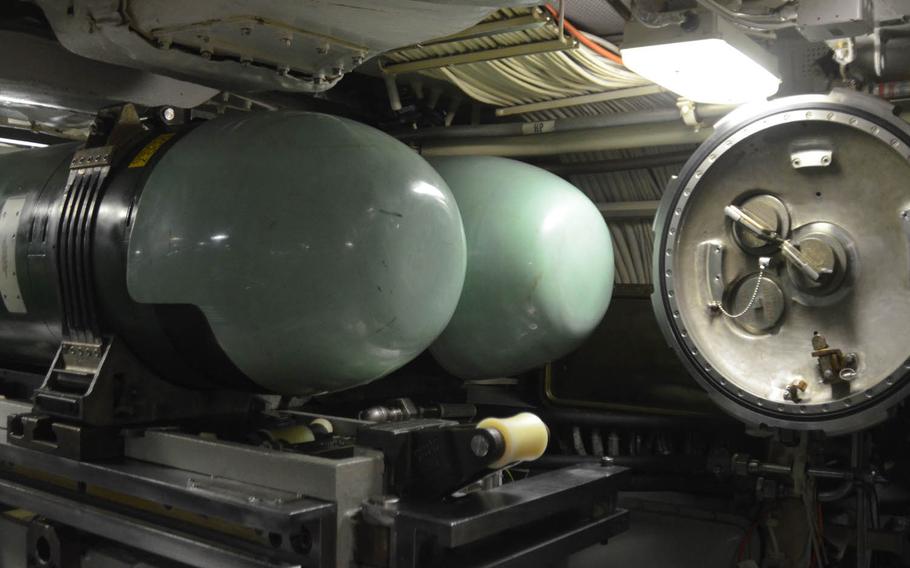

Two of the USS Michigan's Mk-48 torpedoes lie next to one of the submarine's tubes, as displayed during a port visit at Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan, on July 10, 2015. Two of the tubes can launch both torpedoes and Tomahawk cruise missiles. The two forward-most missile tubes were permanently converted to lock-out chambers that allow underwater deployment and retrieval of special operations personnel. (Tyler Hlavac/Stars and Stripes)

YOKOSUKA NAVAL BASE, Japan — The USS Michigan and three others like it can pack more conventional missile firepower than any other submarines — and in about a decade, they’re probably going away.

Guided-missile submarines like Michigan can also stay at sea longer and deploy larger groups of Navy SEALs than the service’s more plentiful fast-attack subs.

For all their advantages, Navy officials acknowledge they are luxury items in a fiscal environment that doesn’t support building replacements.

As the Navy’s submarine fleet shrinks over the next 13 years due to the retirement of its Cold War-era subs, it will look toward less expensive technology to offset the loss of boats like Michigan, service officials told Stars and Stripes.

However, as long as the Navy has its guided missile subs, they are getting plenty of use. USS Michigan had been on deployment for 21 months when it pulled in to Yokosuka Naval Base for a port visit earlier this month.

“My operational commander would like us to be at sea every minute that I can be,” said Capt. Joe Turk, Michigan’s Blue Crew commanding officer. “The only thing that limits sustainability is food.”

Michigan’s separate Blue and Gold crews typically fly from Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor, Wash., to Guam every four months or so, where they swap out command of the boat.

Michigan entered service as one of the Navy’s 18 Ohio-class nuclear trident missile submarines, known colloquially as “boomers.”

When the Navy cut the number of nuclear-missile subs to 14, it converted four of them to carry up to 154 Tomahawk missiles.

The four submarines began global deployments during the past decade. In 2011, the USS Florida took part in a guided-missile submarine’s largest-scale conventional combat operation when it fired 90 Tomahawks in the effort to defeat former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi’s forces.

When a guided-missile submarine isn’t firing Tomahawks, it functions much more like a smaller fast-attack submarine, though it retains the typically higher-ranking captain and crew structure of a boomer.

Both the guided-missile subs and fast-attacks conduct surveillance, train to fight ships and other subs, and conduct special operations.

Guided-missile subs have multiple lockout chambers to deploy SEALs and their vehicles underwater. They also have an extra 200 feet of length and a little more width than fast-attack subs, meaning special operators have more room to get comfortable, said Capt. Brian Humm, commodore of Submarine Squadron 19.

“[Special operations] is physically intensive — they work hard,” Humm said. “It’d be nice if they had own racks, it’s nice that they have tons of gear to work out with and … larger facilities.”

However, those are amenities that aren’t likely to last into the long term.

The current 30-year Navy shipbuilding plan calls for guided-missile subs to be decommissioned between 2025 and 2027.

By October 2028, the total number of attack and guided-missile subs would drop to 41, down from 57 today, before climbing back to 48 boats in 2036.

As those numbers drop, the Navy will also ask Congress to fund an Ohio-class replacement in order to preserve what the Pentagon considers the most survivable leg of its nuclear deterrent.

It will cost the Navy $96 billion to acquire the 12 ballistic missile submarines slated to replace the 14 Ohio-class subs carrying nuclear payloads., according to a 2015 General Accountability Office estimate.

At that price, no one has pushed hard to build four more as guided-missile subs. Instead, many in the Navy and Congress are backing an addition that would add more armament to the latest class of fast-attack subs.

The Virginia Payload Module would lengthen the mid-section of Virginia-class subs and allow them to carry 76 percent more torpedoes and Tomahawks. The addition would increase cost of the $2.8 billion subs by 13 percent, according to a Congressional Research Service report in June.

That figure doesn’t include the Tomahawks themselves, which cost about $1 million each, depending on what cost factors are included.

For now, multiple sailors aboard USS Michigan said they were happy to serve aboard a boat that combines fast-attack missions with Ohio-class dimensions.

There are a few more systems aboard a guided-missile sub than on a fast-attack version; however, most of what gets learned to earn “dolphins” — the distinctive pin worn by a submarine-qualified sailor — transfers seamlessly to any of the Navy’s boats, said Chief of the Boat Jason Puckett, of Columbus, Ohio.

“The basics of being a submariner are the same, no matter the platform,” Puckett said.

slavin.erik@stripes.com Twitter: @eslavin_stripes