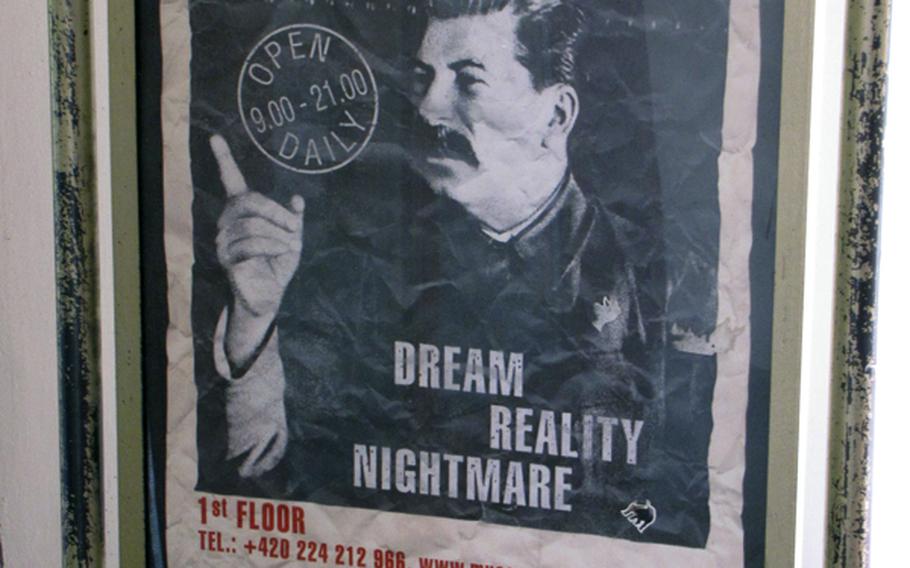

The entrance to the Museum of Communism in Prague, Czech Republic, is marked by a poster of Josef Stalin. Visitors can see the sorry history of communism?s repressive stay in Eastern Europe, focusing on what was then Czechoslovakia. The Czechs and Slovaks split amicably in what is called the Velvet Divorce in 1993. (Stars and Stripes)

All around Prague, construction workers are busy repairing road and rail, fixing sidewalks, and renewing what has to be considered one of Europe’s architectural jewels.

But up the stairs at Na Prikope 10, you can get a glimpse of the very different Czech city of just 20 years ago.

The city’s Museum of Communism is a shoestring operation, but is one of the “must-sees” in a city that abounds with must-sees. It focuses on the hardships and terror endured in a totalitarian state and the will of a people to be free.

A very brief history: Czechoslovakia came into existence in 1918, a successor state to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It survived German domination in World War II but fell into the Soviet sphere of influence after the Yalta Conference of WWII victors settled on the reconstruction of war-torn Europe. The people chafed against the restricted freedoms of travel and media, and briefly liberalized during the period known as the Prague Spring in the late 1960s.

Moscow, of course, freaked. After failed negotiations, Soviet tanks rolled into Prague on Aug. 21, 1968. Czech leaders were summoned to Moscow and returned home promising that liberal reforms would continue, knowing full well that the Soviet Union had no intention of allowing anything of the sort. In their view, the socialist system was perfect and dissent would not be tolerated.

As you wander the museum, you see this “perfection”: representations of the decimated economy with its empty shops, the laughable technological “advances,” and the terrifying sterility of interrogation rooms where dissidents were questioned and beaten — and sometimes disappeared.

The Soviet propaganda is hilarious, but not quite as funny as the satirical takes on its posters, such as the one with the wholesome woman marching with a Russian flag: “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.”

Then there is the display on Jan Palach. Soon after the 1968 invasion, it became apparent to Czechs that the promises of continued reform were hollow, and protests began in nearby Wenceslas Square. To protest the occupation, Palach, a 20-year-old student, lit himself on fire in the square.

His funeral drew tens of thousands. It was a measure of the Czech desire to throw off the yoke of communism. So spooked were the communist leaders by Palach’s legend that they dug up his grave in 1973 and moved it to the countryside to deny Czechs a place of pilgrimage.

While the museum’s exhibits focus on Czechoslovakia, they also put events going on there in the context of what was happening elsewhere. Near the end of the tour, you see a video of the period from 1968 until the crazy last days of the Soviet Union — Matthias Rust landing his plane on Red Square, the Solidarity movement in Poland, and finally the massive protests in Prague that dissolved its authoritarian government. It’s very moving; you witness the break in the chokehold as more and more young people withstand the baton blows of a confused and dying empire and insist on self-determination. There’s something deeply satisfying about watching a bully get punched in the face.

Our older readers will remember those days. Being stationed in Europe as the USSR collapsed was to run home after work and turn on the news, every night, and watch another client government fall and another rally of Eastern Europeans, tears streaming down their faces as they saw a new, bright future.

If I had a complaint about the museum, it would be that there are far too many items without explanations. There are displays of store counters from the Communist era, but nothing to say what the items were, what lines were like, etc.; nothing to give the visitor a real sense of what the experience was like.

But you understand well enough. And you only need to return to the streets to see a vibrant city filled with shops, laughter and men in hardhats building that bright future.