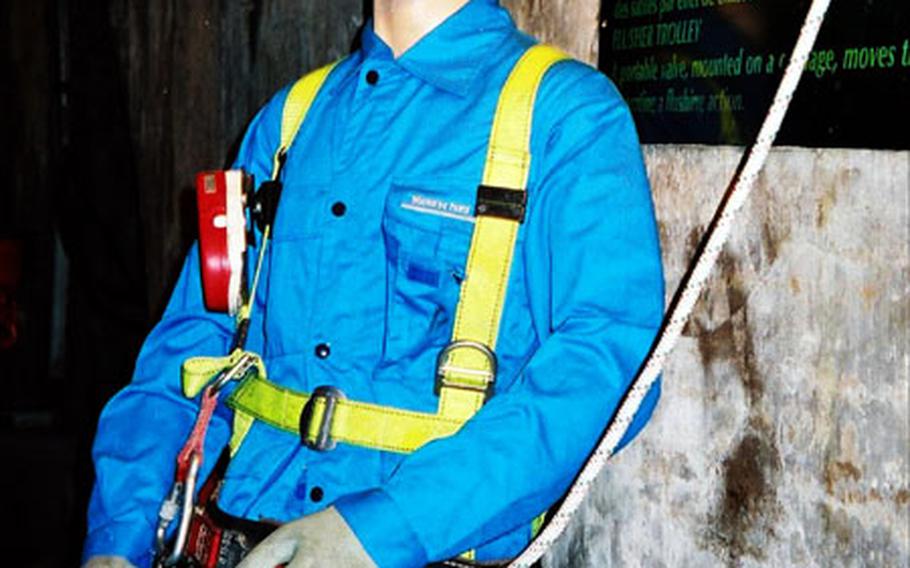

A mannequin shows the uniform and protective gear worn by those who work in the sewers beneath Paris. (Photos courtesy Mary Medland)

Along the banks of the River Seine in the heart of the City of Light lies the entrance to one of the world’s most unusual museums.

Here, literally in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, one puts aside views of one of the world’s most beautiful cities and descends to a kind of parallel universe: that of the sewers.

Below is a world unto itself, one that, in its own way, is about art and culture. Victor Hugo wrote: “Paris has beneath it another Paris, a Paris of sewers, which has its own streets, squares, lanes, arteries, and circulation.”

Indeed, Hugo found the sewers so fascinating that he gave us the indelible image of hero Jean Valjean fleeing his pursuers through them: “All dripping with slime, his soul filled with a strange light.” And at the Musée des Egouts (Museum of the Sewers) visitors can see firsthand what Hugo found so fascinating.

This is a serious museum about a serious subject, and its guides hold visitors enthralled with the surprisingly complex history of the Paris sewers. Exhibits, original equipment on display, films, and tours in both French and English only begin to convey what life in the underground was like.

Such tours, odd as they may seem to many, are nothing new. Almost from the beginning, there were sewer tours, as men and women dressed in their finest clothes were whisked along through the tunnels in modified sewer boats. Without some way to remove the 10 million gallons or so of wastewater generated each day in Paris, the city would soon be awash in its own effluent, as it was throughout much of its 2,000-year history. The idea was to show just how progressive and sanitary the system (and Paris) really was.

While most of the 1,200-mile Paris sewer system dates from the last hundred years, sewers are nothing new. The classical Greeks and Romans were masters at sewer building, and Paris began its system in earnest in the 12th century.

But it took a booming population, cholera epidemics, and a succession of leaders in the mold of Napoleon to create the amazing system of today.

In the 19th century, France had some of the finest engineering schools in the world. The planning genius of Georges Haussmann, prefect for the Seine, and the construction skills of engineer Eugene Belgrand, made Paris a truly modern world capital. Haussmann, most famous for the sweeping boulevards and physical makeover of the city aboveground, was also responsible for the creation of the maze below the streets.

His system of “sewers” consisted of tunnels — some large, some small — beneath every street in Paris. They were intended as storm drains, carrying rainwater and the detritus of the streets safely away, out of sight and out of mind.

Only when the dirt and trash of a busy city were washed away by an army of street cleaners was it possible for the city to be a truly beautiful metropolis. But, by the turn of the century, Parisians had adopted a policy of “tout-a-l’egout” — “everything to the sewers.”

The Paris sewer system closely follows the pattern of streets above, and functions very much like the human body. It delivers fresh water through water mains hung from its walls and ceilings, and removes sewage (some in separate, closed sewage pipes likewise hung in the tunnels). As Nathalie Langlet, our guide through this underground universe, explains, sewer workers learn to tell by touch whether the pipes carry fresh or waste water.

Here also are the nerves of a modern city — telephone cables, fiber optic lines, electrical wires, pneumatic tubes — bewildering in their complexity. It also means that a variety of utility workers and repairmen spend a considerable portion of their working lives in such a challenging location.

In the sewers, no one works alone. Workers are vaccinated frequently to protect their health, as best as possible, and are outfitted with an assortment of boots, a gas detector that, when it rings, directs them to put on their masks. Because explosive gasses can build up in the close confines of the sewers — everything from naturally occurring methane to vapors from dumped gasoline — most workers use battery lanterns much like miners.

While at one point, sewermen walked in the muck, today there are ramps. In the event that a worker falls into the mess — “And they all do, at least once,” says Langlet — a harness minimizes the danger of drowning and eases the task of liberating the poor employee.

Of course, she adds, the first rule of such a fall is to keep one’s mouth shut. But, that doesn’t always happen. “In that case, it’s straight to the hospital,” she says, wrinkling her nose.

The backbreaking work of flushing the sewers and keeping the system in good repair is a daily chore. Each year, men and machines haul more than 15,000 square yards of grit and muck out of the tunnels so that the gray water of Paris can flow downstream to the treatment plant at Acheres, the largest such plant in Europe.

“But the people who work here in the sewers love their work,” Langlet assures us.

Today, around 700 workers keep the sewers of Paris in tip-top shape, many following their fathers and grandfathers into the profession. It is a line of work strenuous enough to force workers to retire at age 50, often with significant health problems. The humidity causes bone problems, and the gases, or miasmas, damage the lungs.

Nevertheless for many years, the position of egoutier was highly sought after, although not because of status, and certainly not because of the work itself. The pay was good, it was year-round employment, and for the most part, the men worked in small groups free from oppressive supervision. As in mining and other kinds of important but difficult work, jobs were passed down through families.

But the sewers are also home to an assortment of unappealing animals: roaches, snakes, poisonous spiders, and for a brief time, a crocodile that escaped from a local zoo.

And then there are the rats.

These remarkable creatures act somewhat as sewer hygienists, each consuming three times his body weight in waste material every day. On the other hand, because these rodents breed with such remarkable speed, Langlet said maintenance crews periodically lay poison to keep their numbers manageable.

As one might expect, all sorts of things turn up in the sewers. Workers wear gloves to protect against discarded syringes, and sewermen have been responsible on more than one occasion for providing local police with the murder weapon that was tossed their way. And of the approximately 3,000 calls annually for help in locating items accidentally dropped, the retrieval rate is a remarkable 80 percent.

Remarkably the museum itself is nearly spotless. It is well-lighted and spacious, although damp, but one never forgets that this is an alien environment well below the bustle of the streets.

Over the years, a rich body of myth and legend grew up around the Paris sewers. Hugo merely enhanced the popular perception of a criminal underworld — complete with the darkness and foul smells resulting from corruption and hopelessness — dwelling there.

Perhaps a few clever revolutionaries used the sewers as hiding places or avenues of escape. But ask any sewer worker today whether the tales of daring escapes and secret underground adventures are true, says Langlet, and you get an immediate answer even Americans can understand: “impossible.”

In the end, Musée des Egouts isn’t really about wastewater, or engineering, or about visiting odd and unusual places. It is about the making modern Paris and the striking blend of art and craft that distinguishes France.

Mary Medland is a freelance writer living in the United States. E-mail her at:memedland@aol.com.

If you go ...

The Musée des Egouts is at Pont de l’Alma, on the left side of the river opposite 93 quai d’Orsay.

HOURS: It is open 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday through Wednesday from Oct. 1 through March 30; and from Saturday to Wednesday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. from May 1 to Sept. 30.

The museum is closed Thursday and Friday, and during the last three weeks of January.

ADMISSION: Entrance is about 4 euros for adults; 3 euros for seniors and students; 2.50 euros for 5-12 year-olds; free for under 5.

TIPS: It’s best to go on a sunny day. Too much rain and the museum must close. Wear comfortable closed shoes. Tours run about an hour and invariably visitors break up into groups for a French- or English-language version.

— Mary Medland and Stars and Stripes