()

When you initially attacked for seven days and nights without halting for rest, you met and defeated twice your own number. Your advance required the enemy to turn fresh divisions against you, and you in turn hacked them to pieces as you ruthlessly cut your way deep into the flank of the “bulge.” Your feats of daring and endurance in the sub-freezing weather and snow-clad mountains and gorges of Luxembourg are legion; your contribution to the relief of Bastogne was immeasurable. It was particularly fitting that the elimination of the “bulge” should find the Yankee Division seizing and holding firmly on the same line held by our own forces prior to the breakthrough. I am proud of this feat by you as well as those you performed earlier. We shall advance on Berlin together.

— Feb. 1, 1945, Headquarters 26th Infantry Division,W. S. Paul, Major General, U.S. Army Commanding

Mary Ellen Sullivan carried a yellowed copy of this commendation awarded to her father, 1st Sgt. Edward J. Sullivan, as well as a commendation letter signed by Gen. George S. Patton Jr., when she traveled to visit battle sites, military museums and cemeteries in Belgium and Luxembourg this summer.

Edward Sullivan, who died in 1977, fought in the Battle of the Bulge, also called the Battle of the Ardennes, one of the largest land battles of World War II and the worst battle in terms of losses to the American forces in that war.

“He never talked about war,” Sullivan recalled. Her father was one of three brothers who fought in the war, and all survived.

“My father always said he was in Patton’s Army and he was very proud to be a veteran and to have served his country, yet he never went into specifics about the war,” she said.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the great battle that was fought between Dec. 16, 1944, and Jan. 25, 1945. Mary Ellen Sullivan, who works in marketing for American Airlines, was on a press trip sponsored by the Belgian National Tourist Office this spring. The group attended Memorial Day ceremonies in Bastogne, a Belgian town that served a pivotal role in the battle.

“I didn’t realize how emotional this would be. I just feel I’m here for him,” she said. “I was thinking to myself that it’s so wonderful that the people in Bastogne never forgot. They still know how much the Americans did for them.

“I saw a movie yesterday [on the battle] and realized how cold it was. My father suffered from frostbite to his feet all his life … When we got to the cemetery and saw all those crosses, it was overwhelming.”

The Battle of the Bulge actually was a series of battles scattered over several hundred miles and involving more than 1 million combatants, including 500,000 U.S. troops, 500,000 Germans and about 55,000 British. Americans suffered 76,890 casualties, including 19,000 killed and 23,554 captured. Germans suffered about 100,000 casualties — killed, wounded or captured.

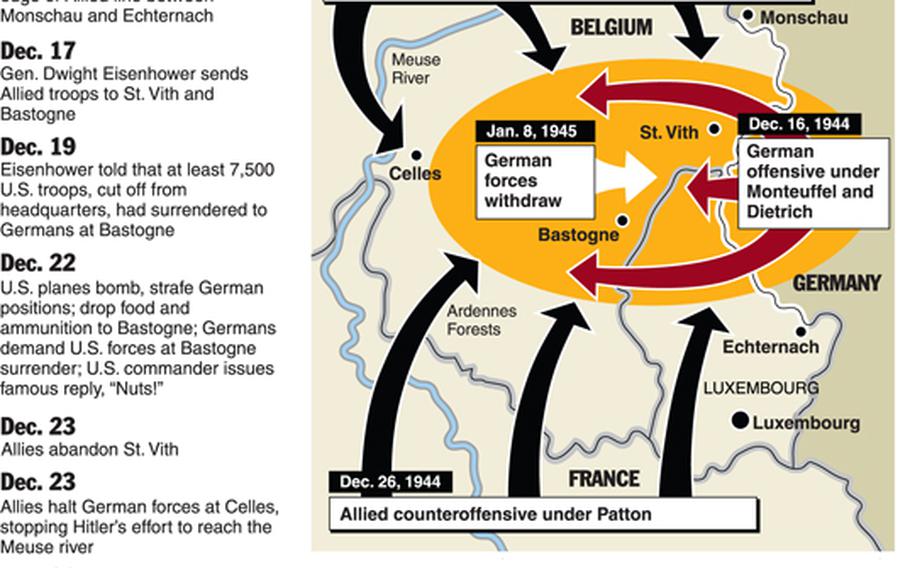

On that wintry mid-December day in 1944, the calm that Belgium and Luxembourg had enjoyed since they had been liberated the previous September was shattered. Three powerful German armies plunged into the semi-mountainous, heavily forested region of eastern Belgium and northern Luxembourg. A heavy artillery barrage pounded American forward positions, followed by the infantry onslaught and the breakthrough by the armored columns.

The Germans’ objective was to reverse the course of events by striking through the Ardennes, crossing the river Meuse and retaking the port of Antwerp, which had been reopened to shipping. They hoped this would isolate the British army from U.S. forces and result in a separate peace on the western front.

They caught the Allies by surprise as American commanders thought the Ardennes the least likely spot for a German offensive. The U.S. kept the line thin, concentrating manpower on offensives north and south of the Ardennes. The poor weather — snow, bitter cold and impenetrable fog — grounded Allied aircraft and greatly aided the German advance.

Those first few days, many U.S. troops were overrun or surrendered. Yet the Americans put up strong resistance in many areas, and within three days powerful reinforcements arrived.

In the snow and with temperatures below freezing, the Germans failed to reach the Meuse. Their tactical objective was no longer Antwerp, but Bastogne.

Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, Europe, dispatched Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division (from Patton’s Third Army), to the town. They arrived on Dec. 18 and immediately split into three combat teams, which established blockades on the most dangerous roads leading to Bastogne. Two were overrun, yet their actions were significant in the successful defense of Bastogne.

The Germans attacked with three divisions, but the Americans held them back. Yet by Dec. 21, Adolf Hitler's German troops had encircled the town. They sent envoys to the American camp, presenting the commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, a demand to surrender. His reply — “Nuts” — has become legend.

Over the next five days the Germans launched a series of 17 vicious assaults on the town, supported by massive bombing. Facing overwhelming odds, McAuliffe stood firm. The bombing continued on Christmas night, but by the next day relief forces from the 4th Armored Division of Patton’s Third Army arrived. On Jan. 3, Allied forces launched a counter-attack and within days Hitler’s soldiers began to withdraw, although fighting continued until Jan. 15.

A week later, the Allied forces had linked north to south and began the push back. By Jan. 28, Allied troops had forced Hitler's troops back to original positions behind the Siegfried Line, and the Battle of the Bulge came to an end.

All the Germans had accomplished was to create a “bulge” in the American line. In the process they expended irreplaceable men, tanks and materiel. After weeks of grim fighting and heavy losses on both sides, the bulge ceased to exist.

Leah Larkin, a member of the Society of American Travel Writers, is a journalist who lives in France.

Find more information at www.amba.lu and/or contact the Bastogne Tourist Office at (+32) (0) 6124-0961, or www.bastogne.be.