1659: A real war on Christmas. ()

WASHINGTON — Christmas is a time for family gatherings, gift-giving, carols and holiday cheer — a season now embraced by Christians and non-Christians alike.

But it wasn’t always so.

Christians have long marked Christmas as the birth of Jesus, but most modern Christmas customs are a relatively recent phenomenon, popularized by writers and royals after some Christian groups had sought to tone down the commemoration.

Why December 25th?The New Testament mentions no date for the birth of Jesus, and historians are divided over how Dec. 25 emerged as a favored date. One theory is that it roughly coincided with a popular Roman holiday, Saturnalia, a raucous period of feasting and partying when servants waited on their masters and many laws were suspended. Northern European pagans also marked the start of winter with their own festivals. Christian missionaries saw advantages in incorporating popular, multi-day festivals — the origin of the terms “yule” or “yuletide” — into the calendar of the new religion they were spreading. Whatever the reasons, by the 4th century Christians in the western part of the Roman Empire were celebrating Jesus’ birth on Dec. 25. The date spread into the eastern areas of the empire but with a change in calendars, the birth of Jesus is now marked by Orthodox Christians in early January.

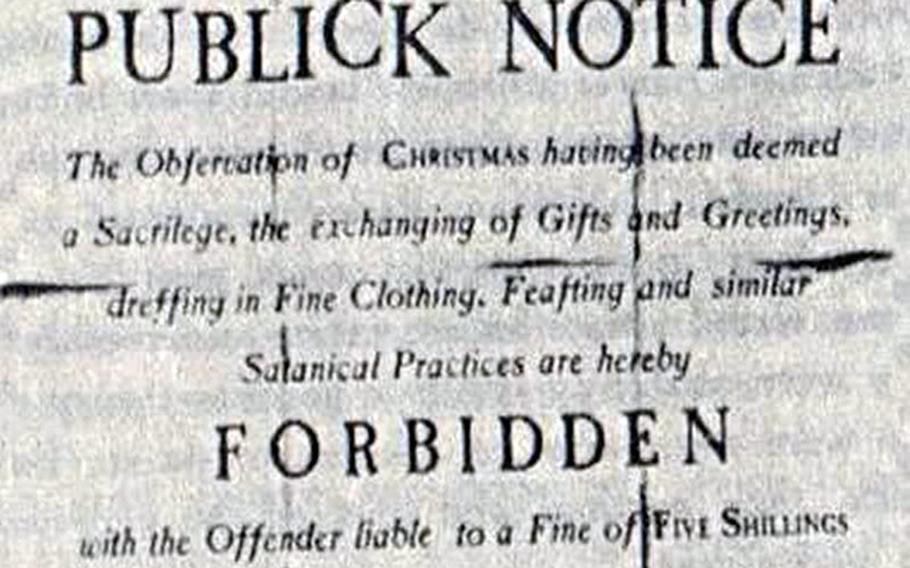

The original 'War on Christmas'Although the Roman Catholic Church considered Easter the most important Christian holiday, Christmas gained in popularity during the Middle Ages, when it was celebrated with feasts and Mardi Gras-style partying. The merriment didn’t always sit well with devout Christians who considered such partying sacrilegious. The Protestant Reformation brought a backlash against Christmas revelry because of the “raucous, rowdy and sometimes bawdy” way it was celebrated, according to Stephen Nissenbaum, author of “The Battle for Christmas.” During the English Civil War that overthrew the monarchy, Puritans led by Oliver Cromwell banned public celebrations of Christmas. When King Charles II restored the monarchy in 1660, he lifted the ban. However, the Puritans in New England held out and declared public Christmas revelry illegal for more than 20 years, removing the ban in 1681.

The birth of the modern ChristmasModern Christmas celebrations began to catch on in Britain and the United States in the 19th century, mostly due to the influence of popular authors and the British royals who imported customs such as decorated trees and gift-giving from Germany after intermarrying with German noble families. American author Washington Irving wrote a series of stories in 1819 about Christmas celebrations in Old England — promoting a sort of 19th century version of “Downton Abbey,” complete with kindly, hospitable squires and their grateful servants. Clement Clarke Moore, a New York professor, popularized Santa Claus in his 1823 poem best known for its opening line “’Twas the night before Christmas.” In London, Charles Dickens promoted the theme of Christmas as a warm, family-oriented season in his 1843 classic “A Christmas Carol.” Meanwhile, Britain’s Queen Victoria and her German-born husband, Prince Albert, brought German-style decorated trees to London in the 1840s. Soon, most English homes incorporated decorative trees and boughs into their own celebrations. The royal family also promoted the idea of exchanging holiday cards. By 1880, nearly 11.5 million Christmas cards were produced in Britain alone. As the holiday spread, the U.S. Congress declared Christmas Day a federal holiday in June 1870.