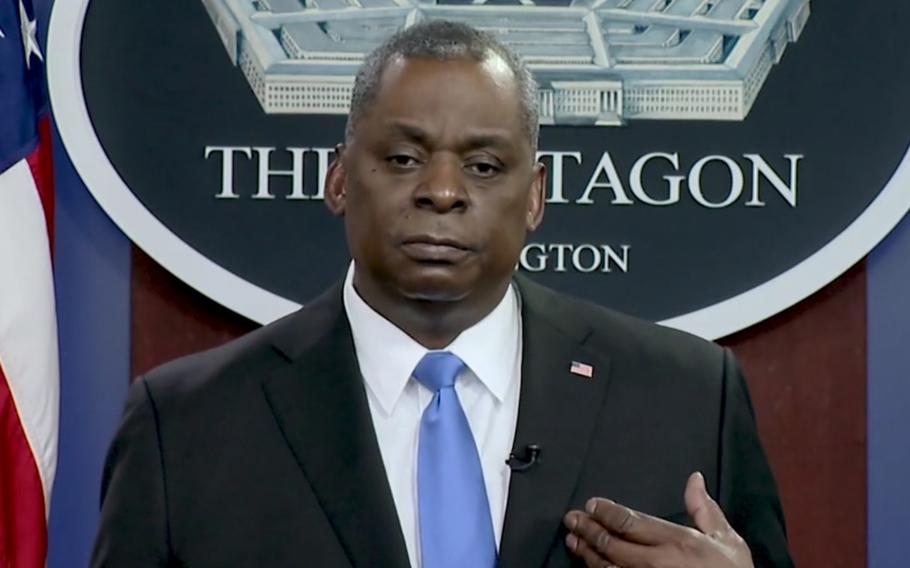

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin speaks to U.S. service members about the coronavirus vaccine in this screengrab of a video posted online Wednesday, Feb. 24, 2021, by the Pentagon. (U.S. Defense Department)

The Pentagon's admission that a drone strike killed innocent civilians as U.S. forces hastily withdrew from Afghanistan undercut one of the Biden administration's chief arguments for leaving — the ability to use "over the horizon" capabilities to hit terrorists.

The risk of drone attacks gone wrong remains.

As vaunted as American drones and satellite technology are, there's still no substitute for boots on the ground, soldiers and agents who can provide the close-up intelligence on possible targets clarifying fuzzy data that's sometimes collected from thousands of miles away.

"You can't fight terrorism just from above," said Christine Sixta-Rinehart, a professor of political science at the University of South Carolina and author of "Drones and Targeted Killing in the Middle East and Africa: An Appraisal of American Counterterrorism Policies."

"You need on-the-ground people walking the streets, working the cities," she said. "You can watch from the sky if you want to, but you can't hear what people are saying."

That's what the U.S. lost after troops completed their withdrawal last month, even as the Taliban regained control of the country. With drones sent from distant U.S. bases in the Middle East, their time to gather intelligence before striking will be limited. And while Afghanistan isn't as much a black box as more isolated nations like North Korea or lawless territories in parts of Africa, officials concede the access to information has become much more obscure.

"Our intelligence-gathering ability in Afghanistan isn't what it used to be," Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said on Aug. 20.

That vulnerability — after a war fought to oust the Taliban, which gave safe haven to al-Qaida terrorists — will be among concerns posed by legislators during hearings on Capitol Hill on Tuesday and Wednesday with Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Senator Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, the top Republican on the Senate Armed Services, sent Austin a lengthy list of questions in advance, including requesting "a detailed description of any operational plan developed by the Department of Defense for future 'over-the-horizon' counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan including the command and control organizational structure."

Despite intense, bipartisan pressure in Congress to keep troops in Afghanistan or at least delay the withdrawal, President Joe Biden gave several reasons for ending America's longest war after almost 20 years. When pressed on how the U.S. would respond if international terrorists regroup in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, Biden and Pentagon officials said America's "over the horizon" military capabilities would prevent that.

It's a tactic the U.S. has put to effect using weaponry such as Reaper drones in other places, including Syria and Somalia. The pilotless aircraft can be deployed with minimal risk to U.S. lives. But those efforts have also faced heavy criticism from human rights advocates, who say U.S. strikes too frequently miss their mark, killing innocent people and ultimately undermining U.S. interests.

In the strike that produced widespread outrage, the military killed what it thought was a terrorist loading explosives into a white Toyota shortly after a suicide bomber's attack outside the Kabul airport. Instead, the drone killed a worker for a U.S.-funded aid agency who had loaded up jugs of water for his family. The 10 people killed included seven children.

"You think you'd kind of know when you off somebody with a Predator drone," Republican Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky told Secretary of State Antony Blinken at a Senate hearing this month. "Guess what: Maybe you've created hundreds or thousands of new potential terrorists."

Secretary Austin, who expressed the military's deep regrets over the mistaken attack, has ordered a review of what went wrong, as has the Pentagon's inspector general.

General Kenneth F. McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command, has described the strike as a "tragic mistake," but cautioned against drawing "any conclusions about our ability to strike in Afghanistan" against Islamic State or al-Qaida targets in the future. He told reporters this month that intelligence on an imminent terrorist attack in Kabul meant "we did not have the luxury of time" to study patterns of activity and other evidence that usually is gathered before a drone strike.

It's hardly the first time a botched strike has occurred.

A study by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in the U.K. estimated that between 4,126 and 10,076 people have been killed by U.S. drone strikes in Afghanistan since 2004. The Costs of War Project at Brown University found that airstrikes killed 700 people in 2019 alone, following the Trump administration's decision to relax the rules of engagement.

Among the debacles in Afghanistan over the years were strikes that decimated a wedding party and destroyed a hospital run by the humanitarian group Doctors Without Borders.

Critics question whether the continued reliance on drone strikes like the one in Kabul is compatible with the administration's focus on human rights.

"In this strike, we see the echoes of so many other civilian lives lost and gravely harmed, whether in wars like in Afghanistan, or outside of them, like in Somalia," Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU's National Security Project, said in a statement. "If President Biden truly means to center human rights, he needs to end the lethal force-first approach of the last 20 years, and also end this country's program of lethal strikes even outside recognized battlefields."

Others question the efficacy of drone strikes, even when they do hit their targets.

"It is sometimes the case that these so-called decapitation strikes can make a strategic difference, but typically they don't," said Rosa Brooks, a law professor at Georgetown University who served as counselor to former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Michele Flournoy.

In any case, she added, "the U.S. track record of hitting the right people and only the right people is not great. Period."

The administration's claim that "over the horizon" capabilities will keep the terror threat in Afghanistan under control is just one of many issues this week's hearings with Austin and Milley will focus on.

Others include why the U.S. military — after a generation of training Afghanistan's officer corps — didn't foresee the force's rapid collapse as American troops withdrew. There will also be scrutiny of the suicide bombing during the evacuation, which killed 13 U.S. service members and scores of Afghans, and questions about American cooperation with the Taliban.

Brooks said the debate over drones is misleading, regardless of whether the weapons are effective.

"We talk about drone strikes as if they're this whole separate category, but they're not," Brooks said. "Their value is only as good as our intelligence and our overall strategy. In many ways the story of the last 20 years in Afghanistan has been tactical success after tactical success and total strategic failure."