Middle East

Special Forces soldiers fight to grant last wish of Iraqi interpreter killed in action

Stars and Stripes September 7, 2018

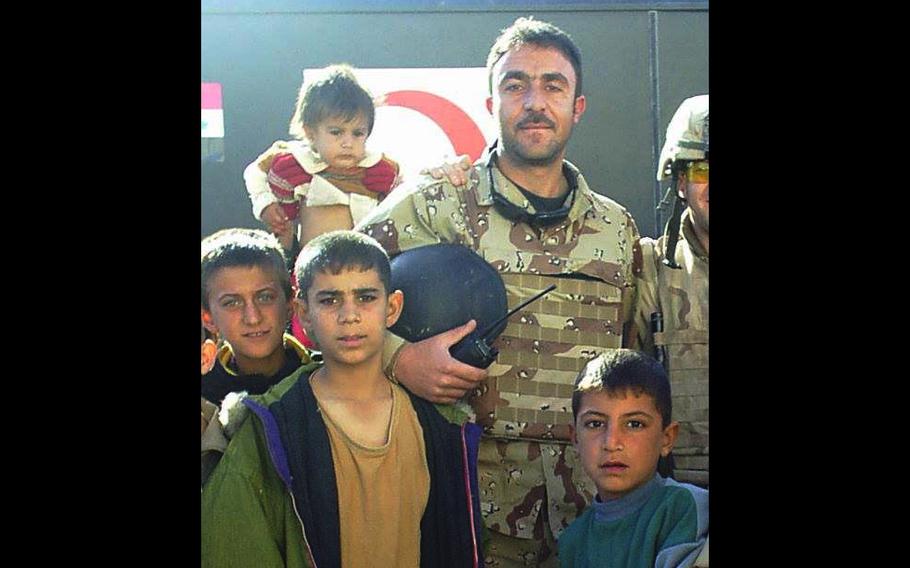

Iraqi linguist Barakat Ali Bashar, known as "Andy" to troops, was killed by a suicide bomber while supporting Army Special Forces in September 2007. (Courtesy of Hadi Pir)

“Take care of my son. Take care of my wife.”

Those were an Iraqi interpreter’s last words to his American Special Forces comrade as he lay bleeding in the desert in September 2007.

Barakat Ali Bashar — known as “Andy” to troops — shielded then-Staff Sgt. Jay McBride when a suicide bomber detonated his vest during a vehicle search near the Syrian border.

McBride, a former Special Forces medic who was shot twice by insurgents as he helped other wounded troops, remembered his friend’s final plea.

So, in 2015, he began writing letters in support of an application for a special visa to bring Bashar’s family of ethnic Yazidis — including his widow, son, mother and brother — to America, after he heard they’d fled their home near Mount Sinjar to escape Islamic State terrorists and were living at a refugee camp in Iraqi Kurdistan.

McBride served three tours to Iraq in 2003-09 with the 10th Special Forces Group and has vivid memories of the mission in which Bashar lost his life.

The Special Forces troops, helped by Bashar and two other interpreters, were training and assisting Iraqi police in their fight against al Qaeda in northern Iraq.

“He seemed kind of young and was a little more western than your typical Iraqi,” McBride said during a phone interview from central Asia, where he works as a civilian defense contractor.

No hope

On his final mission, Bashar flew with eight Special Forces soldiers and a dozen Iraqi police in a pair of UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters over the desert west of Mosul looking for vehicles moving at night in violation of a government curfew.

“It was wide-open barren desert and not a whole lot of reasons for people to be driving it the area,” McBride said. “We would swoop down on vehicles and flash lights for them to stop. If they had a good reason to be out there we’d let them go with a warning, but if they had weapons we’d confiscate them and detain them.”

The Iraqi police took the lead, with the U.S. troops hanging back and pulling security when they stopped a suspicious vehicle.

“I remember seeing [the driver’s] hands go toward his shoulders and then there was a flash. He had detonated a suicide vest,” said McBride, whose body stung with pain as four pieces of shrapnel zipped into it.

Two other Americans, six Iraqi policemen and Bashar were also hit.

“Everybody engaged the driver because he probably had a suicide vest,” McBride said. “We all shot him.”

The group then began taking fire from a nearby village. Though he was shot twice in the leg, McBride was able to aid other wounded.

He found Bashar covered in blood. As he bandaged the serious wounds, his friend kept telling him to take care of his only son, who had been born a week earlier.

“He knew it was pretty bad,” McBride said.

The injured were loaded into the Black Hawks and taken to a military hospital 45 minutes away in Mosul. But when they got there, an X-ray revealed there was no hope for Bashar, who soon died.

“He had dozens of ball bearings in his body causing injuries that nobody could have survived,” McBride said.

‘I owe him my life’

The Special Forces troops made sure Bashar’s family got a compensatory payment; however, McBride, who was on crutches after the attack, worried about them when he returned home a month later.

“I was the last person he talked to,” McBride said. “He said, ‘Take care of my son. Take care of my wife’. That always stuck with me. But I’m just a soldier. I wish I could. Any other day I would have been the guy with his hands on the suicide bomber. All those ball bearings that lodged in him would have gone into me. I wished there was something I could do.”

McBride stayed in touch with another linguist, Hadi Pir, and was heartened when he came to the United States under a program that provided visas for Iraqis who had worked with U.S. forces.

“These guys see more combat than Special Forces operators,” McBride said. “It’s great to see them get rewarded for their effort.”

When McBride and other veterans heard that Bashar’s family had fled their home, they started writing letters and sending emails in support of their effors to come to the United States.

“I owe him my life. I would put them up in my home if that was an option,” he said.

Sgt. 1st Class Michael Swett, another Special Forces soldier, also wrote in support Bashar’s family’s effort to immigrate.

“[Bashar] never shirked duty or responsibility and could always be counted on to steer our team in the right direction,” he wrote in his support letter. “Additionally, he never faltered in his commitment to help American forces in Iraq, even after his family was threatened and their names were placed on a list that was circulated around the region, describing him as a traitor for supporting American forces.

“I would have absolutely no hesitation recommending Barakat’s family be granted citizenship, as they truly epitomize the sacrifice that so many have made during these troubling years of war in Iraq,” he added.

Swett recalled the last conversation he had with Bashar in which they hoped their children might play soccer together in America one day.

After his death, the Special Forces troops conducted a patrol to his village to attend his funeral, Swett wrote.

“We felt so strongly about being there for him that we would risk our own lives to pay respect to his,” he wrote. “He believed in the American dream even more than we did. Unfortunately, [Bashar] never realized his opportunity to see the country that he sacrificed so much for.”

In another support letter, Army Master Sgt. Todd West wrote of his personal sense of debt to Bashar, whom he worked with during a 2005 deployment to Sinjar with Special Forces Detachment Alpha.

“On numerous occasions Mr. Barakat set aside his personal safety and went far beyond his call to duty to assure the safety of our team,” he wrote. “In doing so he made a lot of dangerous enemies in the terrorists and insurgent networks in Northern Iraq.”

In light of the recent savage persecution of Yazidis there, he requested “immediate exfiltration” for Bashar’s family.

“We, the people of the United States of America, put this family at risk and I feel it is our duty as a civilized nation to [ensure] their safety,” he wrote.

Living in fear

In emailed answers to questions from Stars and Stripes Bashar’s family wrote that they’d received about $10,000 in three installments from the U.S. government as compensation for his death but had lived in constant fear ever since. When the Islamic State took control of Sinjar in 2014, they fled, leaving their possessions and personal documents that proved Bashar’s service with the Army. The capture of the documents by the extremists added to the family’s fears that they might be targeted.

Even now, living in a camp in Kurdistan, they worry that Islamic State supporters are living among the thousands of displaced Arabs who have migrated to the region in recent years or even among the local Kurdish population.

“These radical groups target all Yazidis, however, our situation was much harder since even many so-called moderates view people who worked for the US Army and their families as enemies,” the family wrote in response to questions from Stars and Stripes.

Today, they’re struggling to get by in the relief camp and too scared to return to their home in Sinjar, they wrote.

Before his death, Bashar was one of 50 interpreters slated to come to the U.S. under legislation signed by President George W. Bush, the family wrote.

Later, they applied for a special immigration visa under the program for interpreters, which had been expanded by President Barack Obama to include 500 people.

But their efforts were held up by a requirement that they provide the International Organization for Migration, or IOM, proof of Bashar’s employment as a linguist, according to fellow interpreter Hadi Pir.

Bashar’s former employer, L3, referred Stars and Stripes to U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command, which confirmed in an Aug. 30 email that he was employed under a contract with the company to work as a linguist in Iraq at the time of his death.

The family wrote that they had obtained paperwork that proved Bashar “was declared dead in a U.S. Army hospital and he was an interpreter who served with [U.S. forces].”

The case was submitted to immigration authorities; in April the family was interviewed by the IOM and they’re waiting for a follow-up interview with the State Department, Pir said.

But a long wait in such a dangerous place is wrong, he added.

“Is this how you treat a family of someone who worked five years with the U.S. Army; someone who was loyal to the U.S. and Iraq; someone who gave his life serving with U.S. Army soldiers and trying to protect them?”

Twitter: @SethRobson1