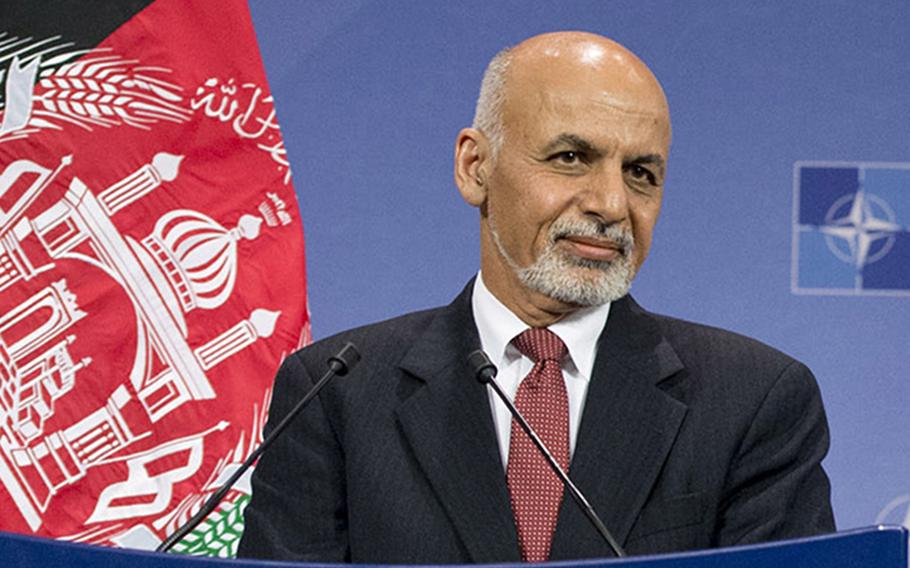

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani at a news conference at NATO headquarters in 2014. Ghani announced a cease-fire with the Taliban beginning June 12, 2018. ( Courtesy of NATO)

KABUL, Afghanistan — Afghan President Ashraf Ghani on Thursday announced a weeklong cease-fire with the Taliban beginning next week, lasting through the end of Ramadan and into one of the holiest periods of the year for Muslims. Both U.S. forces and Afghan security forces will unilaterally cease operations against the Taliban beginning on Tuesday but will continue to target the Islamic State in Afghanistan, al-Qaida and other foreign-backed groups, Ghani and the U.S. military said. Ghani linked the cease-fire to a ruling by 2,000 religious scholars in Kabul on June 4 that declared that the war in Afghanistan was “forbidden under the Islamic law.” The Taliban denounced the clerics’ declaration; subsequently, an attack on the gathering claimed by ISIS killed 14 people and wounded many others. “This cease-fire is an opportunity for Taliban to introspect that their violent campaign is not winning them hearts and minds but further alienating the Afghan people from their cause,” Ghani said. The cease-fire will continue until five days after Eid, which marks the end of the Muslim month of fasting, on June 20. Afghanistan’s Muslims celebrate the Eid holiday for several days, giving gifts, doing works of charity and visiting bazaars to buy new clothes, sweets and snacks. A Taliban spokesman said Thursday it would soon issue a statement. Gen. John Nicholson, U.S. Forces-Afghanistan and the NATO-led Resolute Support commander, said they “will adhere to the wishes of Afghanistan for the country to enjoy a peaceful end to the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, and support the search for an end to the conflict.” In a statement, the U.N. Assistance Mission in Afghanistan welcomed the announcement and urged the Taliban to reciprocate. Afghan and Western diplomats have intensified their efforts to enter into peace talks with the Taliban since at least early spring. In February, Ghani offered the Taliban recognition as a legitimate political group as part of a process to open talks and to end the nearly 17-year conflict. He proposed a cease-fire, release of prisoners, a constitutional review and new elections in which the Taliban could participate. His offer followed a reconciliation and amnesty deal with Hezb-e-Islami, Afghanistan’s second-largest insurgent group led by the exiled Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a U.S.-designated “global terrorist” who was blamed for brutal killings during Afghanistan’s civil war in the 1990s. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Wednesday discussed the need for political reconciliation in Afghanistan in a call with Pakistan’s chief of army staff. Islamabad has participated in efforts to bring the Taliban to the table, but that work has largely been unsuccessful since 2015, when talks fell apart after the death of Mullah Mohammad Omar was belatedly made public. A key part of President Donald Trump’s strategy for the region involves increasing diplomatic pressure on Pakistan. In a New Year’s Day tweet, Trump accused Afghanistan’s neighbor of giving the U.S. “lies and deceit” in return for billions in foreign aid and said it had been giving safe haven to the Taliban. On May 30, Gen. Nicholson told reporters at the Pentagon that the Trump administration’s South Asia strategy had led to increased diplomatic activity and dialogue surrounding reconciliation. He called the process “talking and fighting” and said that the success of such talks depended largely on their happening “off the stage” and in secret. The Taliban later rejected his claims and said it would not negotiate with Kabul as long as foreign troops remained in the country. The militant group is unlikely to respond with a cease-fire of its own, and it may use the respite to consolidate its battlefield gains, said Ahmad Majidyar, researcher at the Middle East Institute. The cease-fire is also unlikely to convince the Taliban to make concessions to the government, he added. “All unilateral concessions in the past, such as freeing Taliban prisoners, have not encouraged the militant group to lay down arms or even agree to negotiate with Kabul for a political settlement to end the war,” Majidyar said. “The Taliban will also see Kabul’s unilateral cease-fire offer as a sign of the government’s weakness rather than strength and will try to exploit it for political and military gains.” The Taliban, now in their spring fighting season, contest or control more than 40 percent of Afghanistan, according to a report this spring by a U.S. government watchdog.lawrence.jp@stripes.com Twitter: @jplawrence3

garland.chad@stripes.com Twitter: @chadgarland