Middle East

A lack of convictions

Stars and Stripes October 16, 2010

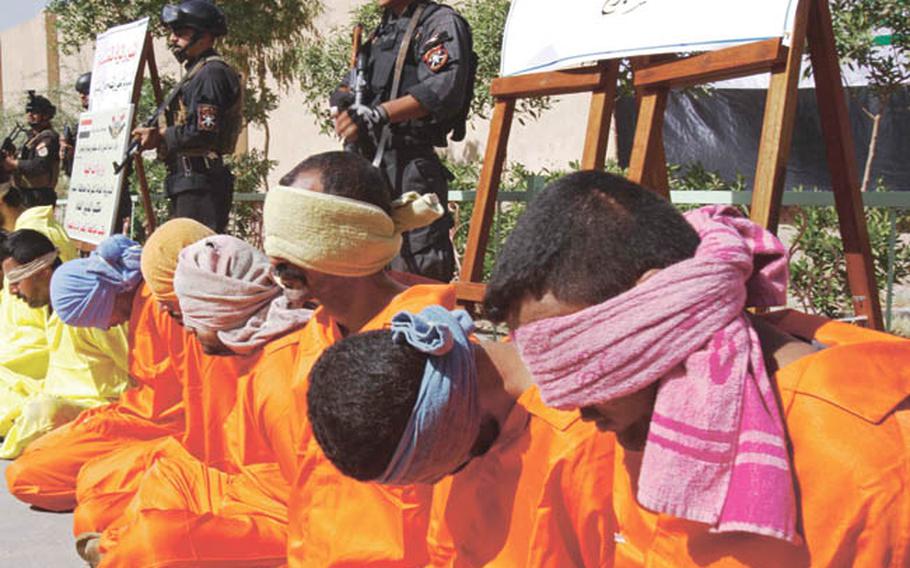

Blindfolded suspects are guarded Thursday by Iraqi special operations commandos, in Basra, Iraq. Security forces arrested 18 men and seized large quantities of explosives, ammunition, rifles and weapons equipped with silencers, along with Katyousha and Grad rockets. What happens next depends on how well the arresting officers coordinated with judicial investigators, U.S. forces say. If proper procedures have not been followed, their cases will likely be thrown out by a judge. (Nabil al-Jurani/AP)

TIKRIT, Iraq - Ziad Yasin Shibib Al-Azawi is worried that the bad guys — the ones lobbing hand grenades at Iraqi soldiers and detonating bombs in marketplaces in Salah ad Din province — are getting away with murder.

But simply making arrests isn’t the solution, according to Ziad, the chief investigator for the High Crimes Courts in Tikrit.

Until prosecutors and judicial officials have built solid cases, and until approval is received to get detainees into court, the arrested will, more likely than not, walk away.

The problem, Iraqi and U.S. military officials say, is that too few people working with the judicial system understand what it takes to put an insurgent behind bars.

“Obviously, it creates this catch and release phenomenon that we were looking to address,” said Capt. Kevin Ley, an Army judge advocate general with U.S. Division-Center in Baghdad who is working to unravel problems behind the low conviction rates.

Lt. Col. Donald Brown, a battalion commander with the 25th Stryker Brigade Combat Team working in Salah ad Din, has directed his officers to figure out how the court system works there.

After working with Iraqi judges, security commanders and investigators like Ziad for two months, Brown’s staff came up with a three-page PowerPoint slide with this title: “How We Think The Iraqis Think Their System Works.”

A confusing system

Though confusion lingers, either the police or the army have the power to arrest, provided they have enough evidence for the case to go forward.

But they must work in concert with the criminal court system’s investigative arm, led by special judges with a staff of investigators who oversee a defendant’s first stop in court.

At one time, it was easier. Judicial investigators worked out of local police stations, signing off on witness statements or evidence collection as the case was built, Ley said. But in the chaos of war, they retreated to the courthouses. And as the army grew and began tracking down wartime criminals, investigators increasingly were left out of the process, he said.

These investigative judges act like district attorneys in the States, working with the prosecution but, in a pretrial courtroom hearing, ruling on whether there is enough usable proof against a defendant before referring the matter to a trial judge. Without casework that includes the approval of investigators such as Ziad, judges will often throw out the case.

“The judges are actually the good news,” Ley said, acknowledging that in the past many U.S. commanders would cry judicial corruption when detainees were released.

“They are implementing the law,” Ley said. “They are going by the code. If there’s not evidence, it doesn’t go to trial.”

Complicating matters further, different provinces handle different types of offenses — e.g., war-related crimes vs. civilian crimes — by moving them through different courts.

“There’s a lot of blur between what is counterterrorism activity and [what is] penal law activity,” said Maj. Patrick Roddy, 33, of Winchester, Mass., the operations officer with the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry Regiment, who works for Brown.

In Salah ad Din, for example, cases involving crimes such as bombings and terrorism are handled by the High Crimes Courts, military officers say. To get an arrest warrant involving a war crime, both the lead high court judicial investigator and the province’s top police chief must sign off on the paperwork.

But in Baghdad, war-related crimes are handled in the same courts as crimes such as robbery or larceny. In the capital city, investigative judges approve warrants without the oversight of a provincial-level police commander, U.S. military officials said.

There is progress

As the U.S. military sorts through the processes, they are finding Iraqi security leaders and investigative judges willing to work together to improve practices.

This summer, Baker and Ley invited a small group of investigative judges, Iraqi army commanders and Ministry of Interior counterterrorism officials from eastern Baghdad to a day of lessons in forensic evidence, and making that evidence useful.

After a day of CSI-like examples and demonstrations by U.S. military personnel, the judges and counterterrorism investigators broke off to talk about how to get such evidence into the criminal casework — an encouraging sign, Ley said. One judge suggested that if a judicial investigator also signed off on the U.S. work, he would accept it as evidence in court.

Last month, frustrated that his soldiers weren’t making any arrests, the Iraqi general in charge of Diyala paid the courts in Baqouba a call. He was told that the soldiers weren’t meeting the evidence standard. The general worked with the courts to hold a class on legal proceedings in arrests, according to Brig. Gen. Patrick Donahue, a deputy commander with U.S. Division-North.

“Since then, (they) got 20 warrants in one week,” Donahue said.

Ziad’s worry about police in Tikrit making rash, unsupportable arrests remains. But there is progress. Now, with U.S. military advisors watching, Ziad and the police are meeting more regularly to discuss the suspects on their most wanted lists.

During a meeting last month, Ziad worked with the police to whittle a list of 80 suspects to 26. The next step was to figure out which suspects had existing warrants and whether those warrants carried enough evidence to merit an arrest.

Yet even in the seemingly simple work of going through a list of suspected criminals, another hurdle became clear.

Before the police in Tikrit can go after new arrest warrants for the 26, the top provincial police chief must approve the paperwork.

That’s not a requirement by law, Roddy and others with the battalion have found. That’s just the way politics and justice work in Salah ad Din.

With about nine months left to advise the Tikrit officials and improve the system before heading back to Hawaii, officers like Roddy aren’t as concerned with this extra step so much as with whether it gets more known insurgents arrested, tried and put into jail.

“This will be huge if we can pull this off,” he said.