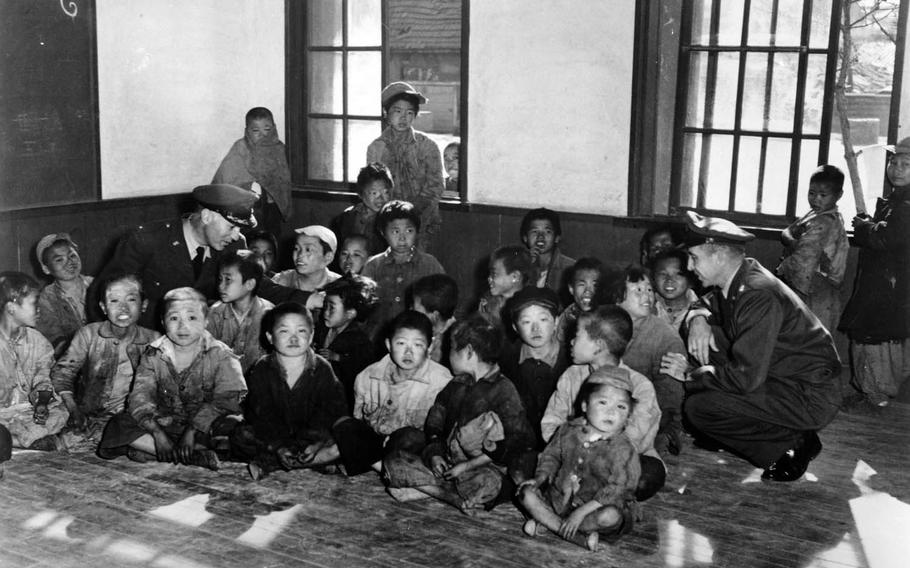

New arrivals at the 5th Air Force's Seoul processing center for orphans, before evacuation to Jeju Island on Dec. 20, 1950. With them are Chaplain Col. Wallace Wolverton, left, and Chaplain Lt. Col. Russell Blaisdell. (Courtesy of U.S. Air Force)

SEOUL, South Korea — Bookended by World War II and Vietnam, the Korean War is often called the Forgotten War.

But a group of survivors, advocates and researchers is determined to keep alive the memory of an Air Force chaplain who led a campaign to save nearly 1,000 orphans as Chinese and North Korean forces closed in on Seoul in 1950.

It’s especially important to honor the late Col. Russell Blaisdell, they say, because he went for decades without recognition for the airlift widely known as Operation Kiddy Car.

“He did not consider himself a hero,” his son and namesake said at a commemoration and symposium in June aimed at setting the record straight.

The gathering, which was held in a hall of the National Assembly members’ office building in Seoul, was timed to coincide with a month of remembrances surrounding the June 25, 1950, start of the Korean War.

Operation Kiddy CarBlaisdell, then a lieutenant colonel and staff chaplain with the 5th Air Force, and other airmen started organizing help for street children after discovering them starving and disease-ridden when his unit arrived in the war-torn capital.

“It was estimated that there were 6,000 homeless children on the streets of Seoul in October 1950, about 4,000 of them legitimate orphans,” he wrote in a 1951 letter presented as part of the symposium.

“Something should be done. But the normal agencies for welfare were not yet in position to take care of the situation.”

Many were placed in an orphanage, but that soon became overcrowded, so a separate center was established with the help of donations and South Korean officials to provide food, clothing, shelter and medical treatment.

Blaisdell, his assistant Staff Sgt. Merle (Mike) Strang and South Korean social workers collected children from the streets and “saved many orphans from near-certain death,” according to an Air Force account of the operation.

The situation reached a crisis point in December as communist forces pushed U.S. forces, including Blaisdell’s unit, south and threatened to take Seoul.

Blaisdell devised a plan to evacuate the orphans by getting them to the port of Incheon and transporting them by ship, but that effort collapsed, according to news articles at the time and his own account.

Instead, he rushed back to Seoul in a Jeep and persuaded Col. T.C. Rogers — the unit’s director of operations and one of the last officers in the city — to arrange an airlift involving 16 C-54 transport planes.

The chaplain pulled rank and commandeered trucks to rush the children and staff from the port to the Gimpo airport the morning of Dec. 20. “Although we were two hours late, the planes waited,” he wrote.

The fleet flew the children and orphange staff to Jeju Island, where they were met by Col. Dean Hess, then a lieutenant colonel and fighter pilot who played a critical role in training the fledgling South Korean air force and also was active in helping orphans.

Hess and Blaisdell continued to be heavily involved in relief efforts for the children in the years that followed.

Fact or fiction?The episode was immortalized in the 1957 film “Battle Hymn,” based on Hess’ autobiography, starring Rock Hudson as Hess. The movie portrays Hess as the hero of Operation Kiddy Car and doesn’t mention Blaisdell, although the autobiography does.

George Drake — a Korean War veteran who has painstakingly documented the rescue operation as part of his efforts to honor U.S. servicemembers who helped children — argues that the book and movie promoted a false narrative that deprived Blaisdell of rightful credit for the airlift for decades.

“Hess arranged to receive the orphans,” Drake said. “He had nothing to do with the airlift.”

Drake, 86, who traveled from his home in Bellingham, Wash., to Seoul for the June 22 symposium, cites contemporary articles by The Associated Press and Pacific Stars and Stripes that included many references to Blaisdell as the airlift’s organizer. Hess, who died March 2, 2015, at age 97, is mentioned rarely for his role in helping the orphans after they arrived on Jeju.

“All of that changed with the publication of Hess’ book and the production of the movie,” Drake said in his presentation.

The Air Force says Hess donated the royalties from the book and movie for the construction of a new orphanage near Seoul and notes both men have been honored “as a great friend of the South Korean people.”

But Drake says Blaisdell was actually forced to defend himself to superiors in the immediate aftermath because responsibility for civilians rested with the 8th Army, not the Air Force.

Blaisdell declined to dispute the issue in 1957 in response to a letter from Strang complaining about what he called falsehoods in the book and movie.

“In regard to doing anything about it, I have decided in the negative. Although I agree with you in principle, the goal of our efforts, in regard to the orphans and also in the evacuation of the Koreans by convoy, was the saving of lives, which would otherwise have been lost. That was accomplished,” Blaisdell wrote.

‘Father of a thousand’Blaisdell’s role in the airlift gained new attention when the story was published in the Air Force’s Airman magazine in December 2000 in connection with the 50th anniversary of the start of the war.

The colonel traveled to South Korea for a reunion with several of the rescued orphans. The South Korean government honored him as a hero.

In 2003, he received the Air Force’s highest award for chaplains, the Four Chaplains Award for extraordinary humanitarianism. Blaisdell died May 1, 2007, at age 96.

Blaisdell’s son, the Rev. Russell Carter Blaisdell, said Hess should be honored for his efforts to help children during the war but not the airlift.

“I agree with my father about Hess. He deserves credit for what he did do,” the 80-year-old pastor said before speaking at the commemoration.

Hwang Seon Min, who was 4 when he boarded one of the planes to Jeju, has never forgotten the man who saved him.

“The image of Chaplain Blaisdell standing by the lives of the 1,000 orphans in the bitter cold remains in my memory as fresh as if it were yesterday,” he said during the ceremony, hosted by the Choong Hyun Babies’ Home.

gamel.kim@stripes.com Twitter: @kimgamel