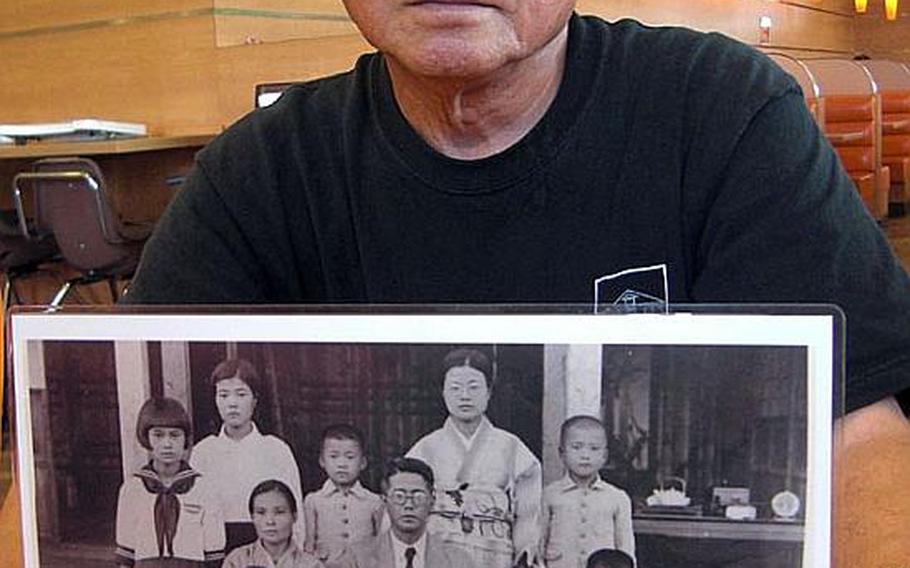

Seiei Kiyuna, 77, who survived the Battle of Okinawa as a child, holds a 1936 family photograph, one of many pictures his father saved from a fire that burned their home during World War II. (Chiyomi Sumida/Stars and Stripes)

CAMP FOSTER, Okinawa — As a child growing up on Okinawa, Seiei Kiyuna had been taught that Americans were evil.

But by the end of the World War II Battle of Okinawa — the bloodiest in the Pacific — he would think differently.

The war in the Pacific was raging 65 years ago, when Kiyuna’s older brother, Seiji, 17, joined the Japanese Imperial Navy to become a kamikaze pilot. The 12-year-old Seiei had hopes of some day becoming a soldier so he, too, could wage battle against the Americans.

Seiei Kiyuna, who along with his parents and seven siblings lived in an area which is now part of Camp Foster, remembers that everyone was willing to do their part.

“It was only natural then to cooperate with and support our own imperial troops,” the 77-year-old said recently.

When metals were needed to produce bullets, he said, Okinawans contributed whatever they could, including pots and pans.

There was no doubt that Japan would be victorious, he recalled.

But that feeling would soon fade after an Allied air raid in October 1944 turned the island’s capital city of Naha into ashes.

With the landing of enemy forces looming in late March 1945, the Kiyuna family and tens of thousands of others were directed to evacuate to the island’s north.

To avoid air attack, Kiyuna said, they hid in bushes by day and walked throughout the night.

On April 1, the first group of Allied forces landed on Okinawa’s west coast, forcing the Kiyuna family to flee to the mountains.

“We ate anything we could — vines, cycad stems, berries, shell fish,” he recounted. “Anything that could fill our stomach.”

By mid-April, a large number of the Allied troops advanced into the north. Thousands of civilians and imperial troops were forced out of their hideaways. Civilians were taken to refugee camps, while those in uniform were sent to prisoner-of-war camps.

But many refused to surrender.

“We were told that once you got caught, you would be raped if you were a woman and brutally killed if you were a man,” Kiyuna said.

Being captured by the enemy was worse than death itself, he remembered many believing. It was under those circumstances that mass suicides took place and people leaped from cliffs to their deaths.

One day, five Americans appeared out of nowhere at the Kiyunas’ mountain hideout with no time for the family to flee.

“Stay still, otherwise we will be shot,” warned Seiei Kiyuna’s father, an elementary school principal.

No sooner was their shack set ablaze that Kiyuna’s father dashed back in to retrieve the family’s ihai (tablets with the family ancestors’ names) and photos of his family and students.

A Japanese-American soldier urged them in Japanese to walk down along the river to safer ground.

“As we were walking by the river, there was a spot where a boulder blocked our way,” Kiyuna said.

They would have to wade into the strong current. But the soldiers then did something that startled Kiyuna. They placed Kiyuna and his two younger brothers on their backs as they waded through the water.

Kiyuna could not believe what was happening.

He was taught at school that Americans were merciless beasts. But the blue eyes in front of him were very gentle, and the young American soldier carrying him kept talking to him to ease his anxiety.

Soon his little body stopped shaking.

“The fear at the moment he picked me up soon changed to big relief,” Kiyuna recalled. After a long trek, they arrived in the Kushi — near what is now Camp Schwab — where thousands of refugees were staged. Kiyuna’s father soon recognized some of his students — many in torn, blood-stained school uniforms, but rejoicing in their reunion.

From that day on, Kiyuna said, he looked at Americans in a different light. While at the refugee camp, he would follow American troops in hopes of learning English.

After fighting ended in the north, fierce combat continued in the south until June 23, 1945, when the Imperial Army’s organized resistance came to an end with the death of Lt. Gen. Minoru Ushijima.

More than 200,000 died during the island battle that lasted less than three months. Kiyuna’s big brother returned home after the war, which ended before his mission as a Kamikaze pilot was fulfilled.

“He never accepted the defeat,” Kiyuna said of his older brother, who became an alcoholic and died at age 25.

Kiyuna, however, would go on to attend an English training school after graduating from high school and land a job with the Air Force provost marshal. He would later meet his wife at one of the U.S. bases he worked at, and the father of three now owns his own business.

“The end of the war to me was the encounter with Americans, who opened up my world,” Kiyuna said.