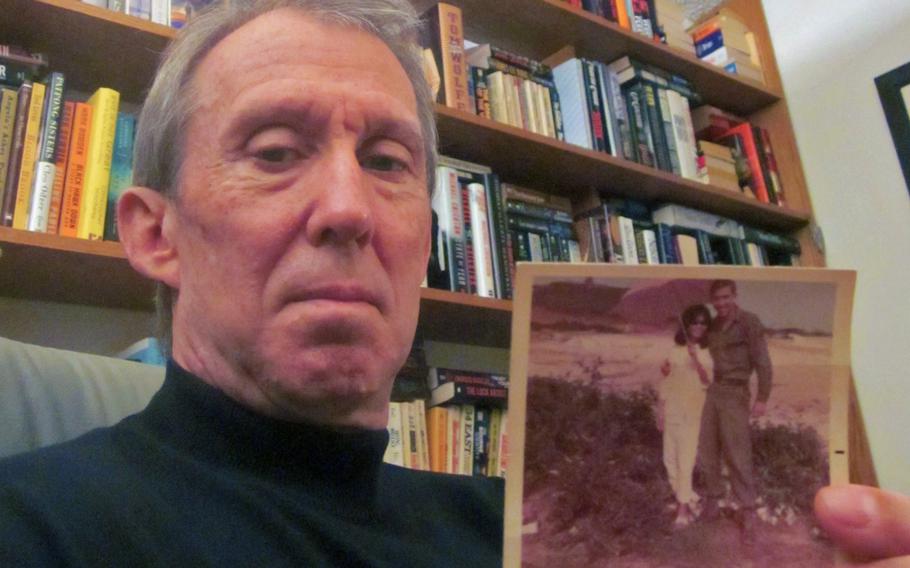

As described by John Wood: "I was a Spec 4 working for the Tactical Operations Center in the Americal Division in Chu Lai, Vietnam, in 1968. I am posing with Joanne, who worked in the An Tan village outside the base. She lived in Tam Ky on Hill 54. I devoted a chapter to her ("The Hellcat of Hill 54") in my memoir Saigon Tease: So, What Did You Do in Nam, Dad?" (Courtesy of John Wood)

As the nation commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, memories of the conflict are coming to light again. Many Americans, if asked what comes to mind about that war, would probably say anger, torment and sadness.

I had a different experience. After so many years, it’s important to know that this chapter in our history had another side.

Fresh out of high school in 1966, I enlisted in the Army because it was the only branch that guaranteed, if I signed as a stenographer, I would not be sent to Vietnam. My recruiter told me no stenographers were being sent to Vietnam or would be. He said the only rice paddy I would see would be in pictures in a book. He said I would have as much chance of getting a Purple Heart as Lady Bird Johnson.

So I enlisted as a stenographer and was promptly sent to Vietnam. And I’ve thanked my lucky stars ever since. That’s because my tour of duty was the most memorable experience of my life.

What I instantly discovered was that the Vietnamese were not at all like what I’d been told. When others would grouse about the base, the climate, the food, the poverty, the women or the Vietnamese, I tuned them out. I was utterly fascinated with the place and the people.

I was assigned to the Tactical Operations Center of the Americal Division in Chu Lai, about 50 miles south of Da Nang. The TOC performed the same tasks that the Situation Room does for the White House: it planned for battle. I worked the night shift, so my days were free. I spent most of that time with the Vietnamese, who to my surprise adored us. Many years later, a Vietnamese explained why: “Of all the cultures we’ve encountered throughout our history, yours has been the closest to ours in terms of personality.” To them, we were kindred souls.

I could attest to that. Every day I hung out with about 20 Vietnamese who cleaned around our hooches and practiced my Army Vietnamese language lessons with them. The boys would try out their newest kung fu moves on me, tug at my uniform and ask what all the slashes and insignia meant, or beg me to teach them bodysurfing again at Chu Lai Beach’s gnarly curl. The girls and old women would pepper me with questions about America.

“Why you always happy?”

Linda’s query was always the most insightful. She was from the neighboring hamlet of An Tan and more mature than the others.

“Why shouldn’t I be happy?”

“Home far away,” she insisted. “Family no here, friends no here, girlfriend no here. America rich, Vietnam poor. In America, you safe, get marry, have babies. In Vietnam, you fight, maybe die. Why you want come here?”

How could I explain that I hadn’t wanted to come there but since my arrival I hadn’t wanted to leave? I’d fallen in love with Vietnam.

After a while, they would wait for me if I wasn’t there or call out “Yohn!” outside my bunk if they spotted me sleeping. For the first time in my life, people looked forward to seeing me every day. Something was happening here. Our cultural differences didn’t bother me or perturb them; just the opposite. We seemed uncontrollably drawn to one another by our very contrast and dissimilarity.

“You have soap, Yohn?” one of the girls asked shyly one day. It just so happened I’d gotten a carton of Ivory soap that my family had sent me. I hated Ivory because my mother used to washmy mouth out with it as punishment when I was a kid.

“Follow me,” I said and led the whole troop into the hooch. They gawked into each of our room cubicles, our lavish stereo equipment, our family pictures, and all the centerfolds. It was as if they were touring an American Guy diorama. I gave them each a bar of soap. As they left, I couldn’t help but notice one girl longingly eying a box of adhesive bandages above my bed. I stuffed the can into my pocket. When the gang clambered into the open-bed truck that took them home every afternoon, I called the girl over. I put the can in her hands and folded her fingers over it. She bowed solemnly and stuffed it into her pants. When the truck rumbled away, she was crying.

From that day on, I collected every gift and supply item sent to me from home or the USO that I didn’t need and handed them out to the hooch gang as they hopped aboard the truck. One magical day they asked me to join them on their ride home. I asked the Motor Pool driver if it was OK, and he shrugged. I hopped in the back with them. From that day on, it became a daily ritual – and my fondest Vietnam memory. As the truck rumbled through the neighboring hamlet, we joked, played and sang the whole way while bouncing along the dirt road under jungle treetops. Our little band had become inseparable.

A few weeks later, I was coming out of the water at the beach when I heard the familiar rumble of their truck approaching. An instant later it zoomed past on the highway 50 yards up the beach. In a blur I saw the entire truckload of Vietnamese waving toward the shore. A moment later, in sound delay, their crescendo reached me: “Yohn! Yohn! Yohn!” For the first time, the enormity of what I meant to my Vietnamese friends struck home.

“Hey Wood, you’re still hanging around them gooks, I see,” my bunkmate said to me one day. I cringed whenever he used that term.

“They your friends now, or what?”

I shrugged, not wanting to get into it.

“Well then, enlighten me, bro. I been in Nam longer than you. I seen my share, and I’m sorry but I don’t see the attraction. Just what is it about them that’s so fascinating?”

Few GIs I knew understood or took the time to get to know the Vietnamese. Like me when I first arrived, the Vietnamese were the ones killing and maiming us, and since the good guys looked like the bad guys, they were all guilty by association.

No GI wanted to be in Vietnam, so anything about the place – climate, culture, food, people, scenery, language – was anathema to them. Many believed it was Vietnam’s fault (not Congress’s or the president’s) we were there, which was why many had a loathing for all Vietnamese and anything Vietnamese. And still do.

I found them more fascinating than any people I’d ever met, and I couldn’t understand why no one else wanted to interact with them. I already knew what Americans were like; I wanted to know what the Vietnamese were like.

Three decades later, I returned to Vietnam. It had taken me that long to go back because I was apprehensive about the reception a returning veteran might get. As I slumped into a chair at the departure gate at Singapore’s Changi International Airport before the final leg of my trip to Ho Chi Minh City, a shadow darkened my seat.

“What you doing here?”

I looked up to see a young Vietnamese man with spiked hair standing above me. His face was emotionless. He was among a small group of Vietnamese who were waiting for the same flight. We were the only ones at this end of the terminal.

He didn’t look angry, but he didn’t look genial either. I was physically and emotionally strung out, embarking on a trip back to a country and a people that Americans had helped lay waste to. I was uneasy about whether my return would be accepted or rejected by the people I once loved and admired. And here was the first Vietnamese I’d seen in years.

“I’m going to Vietnam,” I said.

“Why?” he shot back.

“I’m a tourist,” I replied. I introduced myself in Vietnamese, hoping that would break the ice. He introduced himself in English. This was not going well.

“You in Vietnam before?” he asked, his eyes narrowing.

I nodded.

“When?” he demanded.

The guilt was rising so fast to the surface, I couldn’t even look at him. “During a very bad time,” I said softly.

He stepped back in shock. “Damn, bro, you don’t look older than 30!”

I stared at the floor for a moment before his words sunk in. I looked up and saw him grinning from ear to ear. He hadn’t been angry. He was just being Vietnamese – inquisitive, friendly, open.

When I arrived in Saigon, which everyone still calls it, the people I met were just as gregarious and hospitable as I remembered. But the real test, I knew, would come in Hanoi, the final leg of my journey. This was where Ho Chi Minh was buried, where we dropped 20,000 tons of bombs in the 1972 Christmas bombings, and where they incarcerated and tortured our POWs in Hoa Lo prison (“Hanoi Hilton”). How would the former North Vietnamese treat me in the country’s capital?

I decided to test the waters at Highway 4, a funky bar known for its exotic flavors of rice liquor. It was jammed, so I was escorted upstairs to the open roof where I joined a tableful of Vietnamese college students who were well into their cups of a concoction made from venom from cobra, krait and grass snakes.

They welcomed me in English and wanted to know all about me. They demanded I sing them a song. When I did, they reciprocated with a horrible rendition of “My Way.” I felt like I was back with my old hooch gang. It mattered not at all to them that I was a veteran. Their country, they said, had long ago moved on. Then one young man turned and asked me what I thought about the Vietnamese.

All the students stopped talking, leaned forward, and stared at me.

“During the war, I got to know you fairly well,” I said. “Since then I’ve traveled to more than 25 countries. In my opinion, the Vietnamese are the friendliest and most approachable people I've ever had the pleasure to meet.”

Every single student gasped.

“And you’re similar to Americans in many ways, too. Both of us are easygoing, fun-loving and a little crazy sometimes.”

Their eyes blinked and beamed. Several students grasped each other.

“But finally, and most of all, I find your culture to be incredibly forgiving.”

And then, to my amazement, each young man lowered his head and began to weep.

After a minute, one of them reached over and clutched my hand. “Sir, you make us so happy!”

“Why is that?”

“Because we never hear anything good about our country. We have much to be sorry for, but this is the first time we hear a foreigner say these things. We will never forget it.”

This is the Vietnam and the Vietnamese I remember. During this commemoration period, I intend to pay homage to all who served there – as well as to Vietnam and its people. I hope others join me.

John Wood is a Los Angeles writer. His memoir is "Saigon Tease: So, What Did You Do in Nam, Dad?".