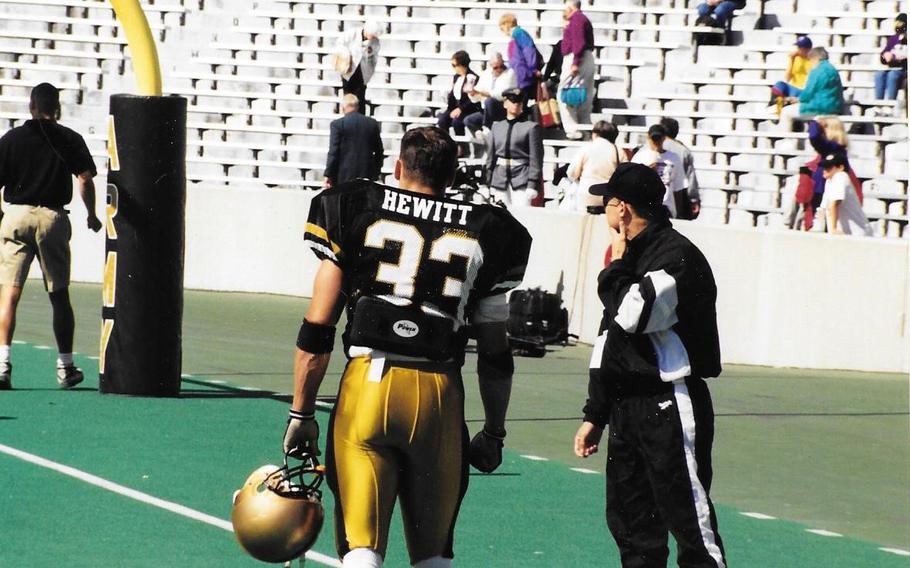

Former Army fullback Joe Hewitt, whose career and education at West Point were cut short by concussions, is part of a class-action lawsuit against the NCAA. (Courtesy of Joe Hewitt)

I am a firm believer that if any of us has a purpose in this life, it is to learn and to teach. One would assume that centers of higher education would agree with this belief.

However, looking back on my college football career at West Point, I wish someone had stepped forward to educate my teammates, and me, about the long-term effects of the game. While it may be too late for many of us, there is still an opportunity for younger athletes to be spared the devastating consequences that come from repeated brain trauma.

Two weeks after I graduated from my Texas high school, I left for basic training at the United States Military Academy. At West Point, I was immediately drawn to its motto: Duty, Honor, Country. Its mission to “create leaders of character who serve the common defense,” Cadet Honor Code, and other values pulled me in and has never let go.

By my sophomore year, I was the starting fullback. It was hard-nosed football, and the tradition of being tough and relying on the people around you was magnified at the Academy. There is no other sport that so closely emulates war, and at the Academy this is our profession.

During my football career, I suffered at least 17 concussions. I don’t remember the details surrounding those concussions, but I know for a fact that they were not treated seriously. Our concussion protocol consisted of sitting out of a week of practice. As long as we were awake and conscious, the other aspects of brain functionality were ignored. There was a game to win. This is part of the culture that permeates football at all levels.

My junior year was when the effects of those repeated concussions took hold: extreme headaches, speech problems, mood disorders and instability, loss of eyesight, seizure-like “tics,” memory loss, and the inability to even make new short-term memories. These symptoms should have been identified earlier, but concussions were not prioritized.

By withholding information that could have drastically improved our quality of life in the long term, the NCAA failed me and so many others. Because by the time you realize there is a problem with your brain, it is too broken to fix.

I underwent testing at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and, based on the test results, I was placed on medical leave for a six-month period, which turned into another six months when the symptoms persisted. Ultimately, military physicians recommended an immediate separation from West Point despite promises that I would be able to graduate. My dream of becoming an orthopedic surgeon was dashed, and I was simply discarded.

Now 40 years old, my symptoms persist. My brain gets overwhelmed by too much light and noise, which seriously affects my ability to live a normal life. Life is a struggle in so many ways, but my greatest fear is my inability to be there for my daughters, and other loved ones, as my brain continues to deteriorate with age.

I decided to join the class-action lawsuit against the NCAA to not only see if there is any help for me, but to prevent this from becoming anyone else’s story. Unfortunately, it has become an all-too-common tale. I can’t help but wonder how my life would be different if the coaches, medical staff and organization had been more forthcoming with their knowledge of potential lifetime damage to the brain.

The NCAA should have cared more about the young athletes under its care. It should have actively pursued education and regulation, for coaches and players alike. The organization knew about the long-term effects of concussions but only cared about its bottom line: money. It is unacceptable that it has become the standard for the NCAA to drop players when they can no longer help bring in revenue. To be dumped to the side, after giving so many years, and to live with permanent damage to your brain is not something I would wish on anyone.

I have to deal with the reality of my life every day. The damage to my health, my life, and my relationships is already done. But the NCAA can, and must, do more to protect its student-athletes. Stories like mine should not be the norm. The NCAA must take responsibility for the role it plays in the lives of young athletes not just while they are playing, but for the long-term injuries they face once their football careers have concluded.