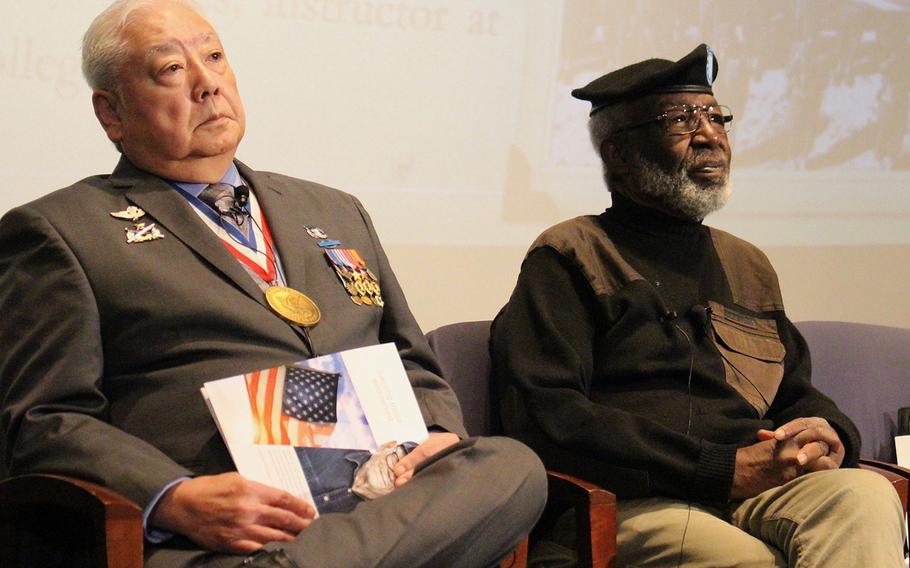

Army veterans Vincent Okamoto, left, and James McEachin take questions during a World War II forum at the 19th annual American Veterans Center Veterans Conference & Honors and National Youth Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C., on Saturday, Nov. 5, 2016. (Ken-Yon Hardy/Stars and Stripes)

WASHINGTON — Korean War veteran James McEachin and Vietnam War veteran Vincent Okamoto said they felt a calling to join the military, deciding as children that they wanted to serve.

Each enthusiastically enlisted in the Army during a time of war and had unique experiences because of their race. McEachin, who is African-American, was part of one of the first desegregated Army units and Okamoto is the most highlydecorated Japanese-American to survive the Vietnam War.

McEachin and Okamoto shared their experiences Saturday morning at a gathering of mostly military academy students at the annual American Veterans Center conference.

Both men were set to receive awards from the center on Saturday night, McEachin for distinguished service in the Korean War and Okamoto for distinguished service in Vietnam.

“In our society, some men are lionized for their great wealth or their political power or their social position,” Okamoto said. “Some are renowned for their athletic ability. Others are accorded celebrity status as film stars and rock icons. Of all the titles in the world, the proudest of that is veteran. Because it refers to an individual who is willing to give up everything for America.”

Okamoto, 72, was born in a Japanese internment camp in Poston, Arizona.

Though his family was unconstitutionally interned for more than three years and stripped of their home, business and belongings, his parents weren’t resentful, Okamoto said.

“I’ve got no bitterness,” he said.

He explained his family were warriors.

Okamoto was the 10th child in the family and the youngest of seven brothers, all of whom joined the military. His two oldest brothers fought in World War II in the all-Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Another of Okamoto’s brothers served as a Marine in the Korean War.

“When the Vietnam War started heating up in the mid-60s, I kind of thought that was my opportunity to prove myself, go off to war and come back and be able to stand with my brothers and drink beer with them as an equal,” Okamoto said.

He recalled being treated as a “pariah” when he entered Vietnam, as most of the new guys were because they posed a threat to the others who “knew the ways of the jungle.” It hurt his standing that he was a second lieutenant and ordering younger men who had more experience in the war zone.

After his first firefight, things got better, Okamoto said. He eventually developed friendships with the men in his company, mostly 18- to 20-year-olds, and created inexplicable bonds.

“They knew what they did was not just thankless, but in some circles wrong,” he said. “They fought, and they risked their lives, and they bled because they didn’t want to let their buddies down. That is something I’ve never been able to see replicated in civilian life.”

Like Okamoto, McEachin, 86, was also inspired by a family member to enter military service.

He described the day his brother-in-law came to his family’s home in New Jersey in 1946 wearing an Army uniform.

“To me, it looked almost like it was from another world,” McEachin said. “I reached my 17th birthday, and the first thing I did was to find someone who could tell me how to join the Army.”

McEachin said he was “particularly happy” with his company, part of the integrated 9th U.S. Infantry Regiment. After his service, McEachin went on to become a novelist and centered one of his books on the 24th Infantry Regiment – one of the all-black regiments created after the Civil War.

He told the story Saturday of a firefight in which he was shot multiple times.

Becoming emotional at times and having to pause, McEachin explained that he was rescued by a fellow soldier, who carried him to safety. All he could remember about the man was his blonde hair. He never learned the man’s name.

Just weeks ago, McEachin returned to Korea to revisit the area near the border between North and South Korea, where he served 65 years ago.

“I didn’t realize I would be so frightened and all these memories would come back,” McEachin said. “It was a little bit too much for me to take.”

Still, he said, he finds “something magical in being called a soldier.”

McEachin has published several books and short stories and has worked as an actor and screenwriter. Okamoto went on to be a superior court judge for Los Angeles County.

McEachin earned the Silver Star and Purple Heart, and Okamoto the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts.

wentling.nikki@stripes.com Twitter: @nikkiwentling