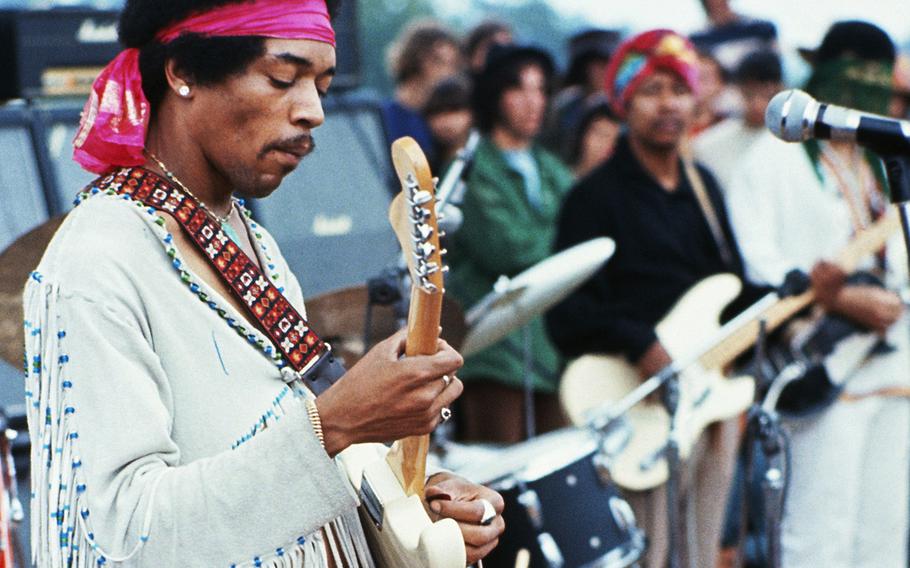

Jimi Hendrix playing his guitar during his set at the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. Playing with Jimi Hendrix is Billy Cox (wearing a turban). (Henry Diltz/Corbis via Getty Images)

On Aug. 18, 1969, former soldier Jimi Hendrix, resplendent in bright red headband, white fringed shirt and bell-bottom blue jeans, unfurled what has been called the cultural moment of the 1960s when he played an incendiary instrumental version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” for remnants of the crowd at the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in Bethel, N.Y.

Hendrix died 13 months later, shortly after his amplified anthem received widespread exposure in the Academy Award-winning “Woodstock” documentary. He was 27. His legacy as a guitar god is unassailable, but 50 years after Woodstock a question remains: Was Hendrix’s performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” patriotism, or was it protest?

The interpretation lies with the listener. At first, Hendrix adhered to the melody of the song, which had only been the official U.S. national anthem for 38 years. By the time he got to “the rockets’ red glare,” though, Hendrix unleashed the full force of his white Fender Stratocaster. The squeals of amplifier feedback and dive-bombing on his electric guitar’s vibrato bar have been said to evoke combat, fighter jets, artillery, ambulance sirens and, perhaps, riots in the streets. It also included a segue into taps, the traditional bugle call played at military funerals.

Popular interpretation, rooted in the mythology of the ’60s, favors protest. It was a complicated time in American history. National pride swelled a month earlier when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, but there was widespread conflict. Civil rights struggles and changing sexual politics made frequent headlines, as did the Vietnam War. As Hendrix performed that 3-minute, 46-second version of the national anthem, the war raged half a world away. More than 35,000 American troops had been killed.

“It was the most electrifying moment of Woodstock, and it was probably the single greatest moment of the ’60s,” New York Post pop critic Al Aronowitz wrote. “You finally heard what that song was about, that you can love your country, but hate the government.” (Francis Scott Key, whose patriotic poem written in 1814 later became “The Star-Spangled Banner,” might have disagreed.)

Noted cultural critic Greil Marcus, who got his start reviewing music for Rolling Stone magazine in the ‘60s, allowed for a more open-ended interpretation in Clara Bingham’s 2016 book “Witness to the Revolution: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year America Lost Its Mind and Found Its Soul.”

“I always think of it as the greatest protest song ever, but it’s not just a protest song, it’s an incredibly layered, ambiguous piece of music,” Marcus said. “To take the national anthem and distort it … it was taken as an attack on the United States for its crimes in Vietnam, which is not an unreasonable way to hear it, but it’s also a great piece of music. No art that has its own integrity is ever going to be about one thing or be one thing.”

Addressing the anthem

Ten months before Woodstock, Jose Feliciano proved that changing the national anthem could bring a backlash. The blind singer-guitarist created a stir when he turned in a soulful rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” more akin to a folk song than a formal performance before Game 5 of the 1968 World Series in Detroit. Many fans were outraged, and even the Tigers and Cardinals players were divided. Feliciano insisted his intent was patriotic.

“I just do my thing, what I feel,” Feliciano told The Associated Press. “I was afraid people would misconstrue it and say I’m making fun of it. But I’m not. It’s the way I feel.”

The heat blew over. RCA Records released Feliciano’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as a single that reached the Top 50. The controversy reignited with Hendrix.

Even in the pre-Twitter era, Hendrix was hounded to explain his motivations. At a news conference a few weeks after Woodstock, Hendrix said, “We’re all Americans … it was like ‘Go, America!’ … We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see.”

He certainly harbored no ill will toward U.S. troops. Earlier in his Woodstock set, Hendrix dedicated “Izabella” to “maybe a soldier in the Army, singing’ about his old lady that he dreams about and humpin’ a machine gun instead.”

If Hendrix was protesting the national anthem or U.S. involvement in Vietnam, he never said so. On Sept. 9, Hendrix again addressed “The Star-Spangled Banner” on “The Dick Cavett Show.”

“What was the controversy about the national anthem and the way you played it?” Cavett asked Hendrix.

“I don’t know, man,” he replied. “All I did was play it. I’m American, so I played it. I used to have to sing it in school, they made me sing it in school, so … it was a flashback.”

Cavett, addressing the audience, said, “This man was in the 101st Airborne, so when you write your nasty letters in …”

“Nasty letters?” Hendrix asked.

“Well, when you mention the national anthem and talk about playing it in any unorthodox way,” Cavett said. “you immediately get a guaranteed percentage of hate mail from people who say, ‘How dare …’.”

“That’s not unorthodox,” Hendrix said, cutting off his host. “That’s not unorthodox.”

“It isn’t unorthodox?” Cavett asked.

“No, no. I thought it was beautiful. But there you go, you know?” Hendrix said, to applause from the audience.

J. Kimo Williams, 69, also thought it was beautiful. Williams, who founded the Lt. Dan Band with actor Gary Sinise, saw Hendrix perform at the Waikiki Bowl in May 1969, just before shipping off to the Army at 19. He was stationed at Fort Ord in California during Woodstock and did not become aware of “The Star-Spangled Banner” performance until checking out the “Woodstock” soundtrack album at the service club in Vietnam.

Williams was so inspired by that Hendrix concert that he immediately decided to dedicate himself to the guitar and a career in music. While serving as a combat engineer in Vietnam, Williams included Hendrix songs in the repertoire of his band, The Soul Coordinators. After returning to the States, he used his GI Bill benefits to attend Berklee College of Music and became an award-winning composer. As a student of music, he sees a simpler interpretation of that Woodstock performance.

“If it had been someone else, on piano, who was a famous classical piano player, and that person decides to improvise over ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ I don’t think there would have been as much of a controversy as [with] Hendrix doing it in his way,” said Williams, who resides in Shepherdstown, W.Va., with his wife, artistic partner and fellow Army veteran, Carol.

“Because he did nothing to the melody to make it sound wrong. He did nothing with the melody or with the … he didn’t say, ‘here’s my protest, and we gotta get out of this war and if we don’t then here you go.’ He played it. He wanted to, you know, the words … it says, ‘the bombs are bursting.’ He wasn’t talking about Vietnam, he was talking about Francis Scott Key indicating in the song that the bombs were going off, so he wanted the bombs to go off. He was actually trying to sonically represent the words of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ and I thought he did a great job of it.”

Whatever Hendrix’s intent, the moment apparently wasn’t planned.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” “wasn’t on the set list!” bassist Billy Cox told Atlanta Magazine in 2012. “We had rehearsed a repertoire and we played that repertoire … And then, Jimi just starts playing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner!’ At first I thought, ‘OK, I know it, let’s do it.’ And then all of a sudden something told me, ‘You better lay out of this one, Billy!’ And what an incredible decision that was. Jimi was one of a kind. That was his moment there.”

Cox continues to honor his friend on the all-star Experience Hendrix tours and with his Billy Cox Band of Gypsys Experience. Long before any of that, Cox and Hendrix were Army buddies at Fort Campbell, Ky.

Army years

Before he was renowned for screaming feedback, Hendrix was, briefly, a member of the Screaming Eagles. The 101st Airborne Division, that is.

Military service was unlikely his preferred career path, although a common one for poor, black teenagers in Hendrix’s hometown of Seattle. The choice became more appealing after he ran afoul of the Seattle Police Department as a high school dropout.

After enlisting in May 1961, Hendrix initially embraced the structure of the Army and expressed a desire to be elite. In his 2005 Hendrix biography “Room Full of Mirrors,” author Charles R. Cross cites a letter Hendrix sent to his father, Al, after getting his assignment as a supply clerk for the 101st at Fort Campbell. Hendrix pledges to “try my very best to make this Airborne for the sake of our name … I’ll fix it so the whole family of Hendrixes will have the right to wear the ‘Screaming Eagle’ patch.”

Despite that early earnestness, military life soon lost its appeal for Hendrix. A chance meeting with Cox led to an impromptu jam. Soon after, they formed The Kasuals and began playing around nearby Clarksville and Nashville, Tenn. As his guitar skills rapidly improved and the number of gigs increased, Hendrix’s interest in soldiering waned. He wanted to pursue a career in music and could focus on little else. He did not want to wait until his three-year commitment was up.

It did not take the Army long to grant his wish. Hendrix was written up for missing bed check, sleeping while on duty and unsatisfactory performance, among other infractions. He was even caught masturbating in the barracks, an act that was likely an intentional ploy to get kicked out of the service. Hendrix often said that a broken ankle suffered during a parachute jump led to his dismissal from the Army, but there is no mention of such an injury in his service records. He was discharged from the Army in June 1962.

Regardless of the reasons, Hendrix was once again a civilian and free to play music professionally. When Cox’s hitch ended a short time later, he and Hendrix formed a new band, The King Kasuals. They toured the collection of black-owned clubs mostly in the South known as the Chitlin’ Circuit, where Hendrix learned showman moves such as playing the guitar behind his back and with his teeth. Eventually a promoter offered him a chance at greater success in New York.

The Experience takes off

That opportunity didn’t quite work out as promised, and Hendrix found himself flat-broke in the Big Apple. At one point, he didn’t even own a guitar. He found session work and spent time playing with the Isley Brothers, Little Richard and King Curtis as well has fronting his own band, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, around Greenwich Village in 1966.

Chas Chandler, the bassist for The Animals, was so blown away upon seeing Hendrix that he offered on the spot to manage him. Hendrix flew to England to seek his fortune. Along with bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell, he formed The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

For all of his struggles in America, Hendrix took this power trio on a meteoric rise up the UK charts in 1967. They scored Top 10 hits in England with “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” in the first half of the year, and their acclaimed debut album, “Are You Experienced,” followed later in the year. The band’s success quickly spread to the United States.

Hendrix returned to America as a conquering hero. One of the enduring images from the Summer of Love is Hendrix setting his guitar on fire at the Monterey Pop Festival in California, kneeling before the burning instrument and coaxing flames from it like a voodoo priest. That performance exemplified Hendrix’s penchant for guitar pyrotechnics and presaged the figurative fireworks of his Woodstock performance by nearly two years.

The Experience recorded two more successful albums, “Axis: Bold as Love” and “Electric Ladyland,” before tensions with Redding led Hendrix to break up the band after a performance June 29, 1969, at the Denver Pop Festival. Eight weeks later, in his debut with his new band, Hendrix encapsulated the spirit of the ’60s.

A time of transition

Woodstock MC Chip Monck introduced the band as The Jimi Hendrix Experience, but Hendrix quickly corrected the record.

“Dig, we’d like to get something straight,” he said. “We got tired of the Experience … it was blowin’ our minds. So we decided to change the whole thing around, and call it Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. Or short, it’s nothin’ but a Band of Gypsys.”

The new band had only been rehearsing for a matter of weeks. Hendrix’s old Army buddy Billy Cox was on bass. Fellow Army and Chitlin’ Circuit veteran Larry Lee, who had returned from Vietnam two weeks earlier, played rhythm guitar. Rounding out the rhythm section were percussionists Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan. They were joined by Experience holdover Mitch Mitchell on drums.

The band’s set that morning was among Hendrix’s longest at 140 minutes, and it highlighted his new focus as a songwriter, bandleader and sonic chemist. It also showcased a performance that for many represents Woodstock itself.

If Cox’s recollection is correct, Hendrix hadn’t planned to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Woodstock, an assertion backed up by Mitchell in his book “Inside the Experience.” It was included in a medley that included “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “Purple Haze” and a free-form jam that became known as “Woodstock Improvisation.”

If Hendrix was planning on making a generational statement, he didn’t let on. “You can leave if you want to,” Hendrix told the crowd near the end of the epic “Voodoo Child.” “We’re just jammin’, that’s all.”

Creating the legend

“The Star-Spangled Banner” quickly became more than “just jammin’.” The performance was Hendrix’s vision, but he had some help in making the moment iconic.

By the time Hendrix took the stage, the crowd at Woodstock was far from the “half a million strong” immortalized in the Joni Mitchell song. He had been offered a Sunday-night slot during the rain-plagued festival, but Hendrix insisted on keeping his position as the closer. As a result, he didn’t play until Monday morning.

Estimates vary, but conservatively the crowd occupying the disaster area that 72 hours earlier had been farmer Max Yasgur’s alfalfa field was half the size it had been at its peak. It’s possible that only a 10th of the attendees remained. Exponentially more people saw it in the theatrical release of the “Woodstock” film or in its countless airings during PBS pledge weeks over the years. One clip of the performance on YouTube has more than 3 million views.

Thelma Schoonmaker, a three-time Academy Award winner for film editing on “Raging Bull,” “The Aviator” and “The Departed,” received the first of her eight Oscar nominations for her work on “Woodstock.” (Incidentally, all three films were directed by her fellow “Woodstock” editor Martin Scorsese.) Whatever Hendrix’s intent, the editors definitely drew a parallel between what was happening on stage and what was happening in Southeast Asia.

“We had decided to go out in the field and film the remnant of the field like it was Vietnam,” Schoonmaker said in Clara Bingham’s “Witness to the Revolution.” “We got beautiful footage, and we used that against Jimi Hendrix playing, massacring ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ with Vietnam sounds.”

The moment, a highlight of the film, might never have happened if not for a bit of good luck.

“Woodstock” director Michael Wadleigh, who was filming Hendrix’s set, was relieved to capture the moment for posterity. In a 2012 interview with NBC’s “Today,” he recalled that he was dealing with an overheating camera and that the volume of Hendrix’s Marshall amplifier kept him from determining if the camera’s motor was running.

“If it weren’t as powerfully photographed, it may not be as famous as it is today,” Wadleigh told NBC. “I remember people literally tearing their hair out. I looked out [from the camera] with one eye and I saw people grabbing their heads, so ecstatic, so stunned and moved, a lot of people holding their breath, including me.

“No one had ever heard that. It caught all of us by surprise.”

“The Star-Spangled Banner” had been heard by Hendrix’s concert audiences. He played the song live nearly 50 times, with more than two dozen of those versions coming before Woodstock. Wisconsin National Guard Sgt. Maj. Brian Bieniek, a Gulf War and Iraq War veteran who is researching a book he hopes to write about Hendrix, believes the Woodstock version is a cut above.

“The Woodstock version had more impact, I think, based on the event it was played at,” said Bieniek, 46, of Madison. “Some of those other [versions] don’t sound as good, and I don’t know if it’s because he was getting the feedback better at Woodstock or depending on what venue he’s at, but … I honestly think that one stands up there at the top.”

Lasting legacy

Hendrix has long been synonymous with the electric guitar, and his legacy has been burnished since his death from drug-induced asphyxiation in September 1970. The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992. Rolling Stone ranked Hendrix No. 1 in its most recent list of the 100 Greatest Guitarists. The writeup in that issue, by Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello, referenced the “riots in the streets and napalm bombs” in Hendrix’s “The Star-Spangled Banner.” In 2011, Guitar World magazine ranked the Woodstock version of the national anthem No. 1 among Hendrix’s 100 greatest performances.

It’s a performance that remains subject to speculation. Because so much of the music played at Woodstock was politically charged (Richie Havens’ “Freedom,” Country Joe McDonald’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag” and the Jefferson Airplane’s “Uncle Sam Blues“), it’s easy to read a statement of protest into Hendrix’s “The Star-Spangled Banner.” From there, it’s not a stretch to draw a straight line to former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s silent anthem protests.

“I think, in retrospect, it divided,” said Williams, who is black. “You had the hippies and you had the non-hippies and then you had the right and you had the left. And so everybody on the left looked at it as a protest, [and] everybody on the right looked at it as almost like kneeling at the national anthem during a football game, as unpatriotic. There was no middle ground. No one just said it was a performance of music, and let’s leave it alone. So as we’ve gone through societal changes ... it’s usually up to somebody far right or somebody far left to decide for the rest of us what is patriotic, what is not, what is an insult and what is not, and the rest of us kind of have to deal with it.”

Hendrix’s performance started an enduring debate, and it has stood the test of time. It came to represent the apex of the hippie ideal, which for many died as a result of the violence at the Rolling Stones’ ill-fated show at Altamont Speedway in December 1969. Whatever Hendrix might have meant on that Monday morning has, as Greil Marcus said, its own integrity.

“I’m pretty sure [the] Woodstock [version of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’] was a protest song, but there’s so many different versions of that, and they range from protest to comradeship to fear to fury, and many, many things besides that,” music journalist, author and SiriusXM radio host Dave Marsh told Stars and Stripes in a 2016 interview. “Of everything in the psychedelic era that was really just out there, musically, and sonically, that is the greatest achievement because he managed to put into it, at various points, so many different perspectives.

“It WAS a generational statement, but it was a generational statement not of protest but of compassion — for everybody, including the Vietnamese. I think it was the most spiritual moment of his entire career, when he would do that song. It wasn’t a gimmick. Not to my ear.”