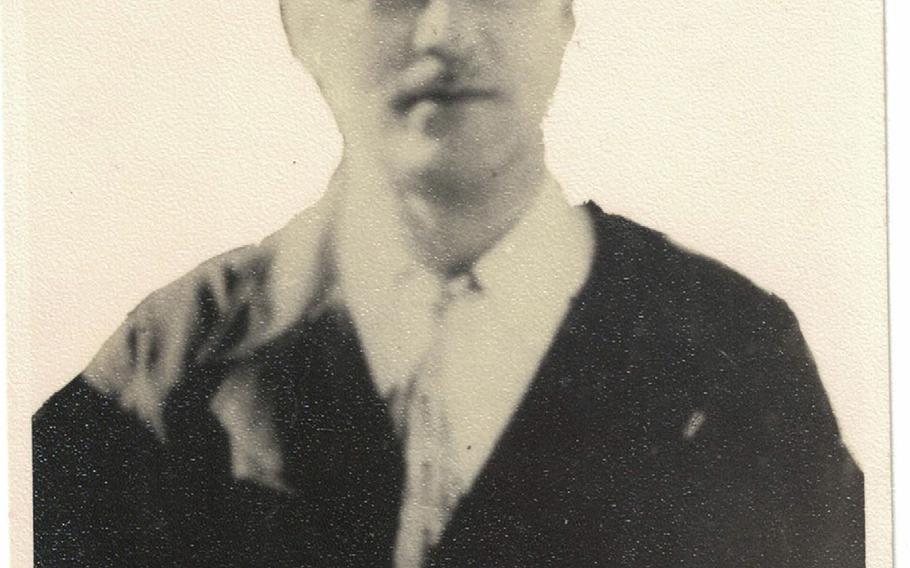

William Evans says his father and namesake was a mining engineer who acted as an adviser to the U.S. military in Seoul when the Korean War broke out. He was captured by the North Koreans and died alongside U.S. soldiers imprisoned by a brutal commander known as “The Tiger.” (Courtesy of William Evans)

SEOUL, South Korea — The list of American civilians lost in North Korea during the 1950-53 war is short. Just seven names, compared with more than 7,000 troops.

But William Evans says the government has a responsibility to try to bring them all home.

His father and namesake was a mining engineer he says acted as an adviser to the U.S. military in Seoul when the Korean War broke out. He was captured by the North Koreans and died alongside U.S. soldiers imprisoned by a brutal commander known as “The Tiger.”

Evans, a 72-year-old retired professor, is hoping his father may be brought home as the hunt for remains gains new attention.

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un agreed during his June 12 summit with President Donald Trump to try to recover the war dead, including “the immediate repatriation of those already identified.”

“I’ve been trying to get his remains back and if at all possible some sort of recognition from the U.S. government for my dad’s services if it can be shown that he did something to help the U.S. Army,” Evans said in a telephone interview during a visit to France.

“It’s not going to bring him back,” he said. “But let him rest where he can be free and not in some communist country like North Korea.”

Tiger group Nearly 7,700 U.S. servicemembers remain unaccounted for since the war ended in an armistice instead of a peace treaty, leaving the peninsula divided by one of the world’s most heavily fortified borders.

Of those, an estimated 5,300 are believed to have been lost in the North, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, or DPAA.

Less known is a list of seven American civilians who died in the war and were not recovered, including Evans’ father who ended up in a group of more than 700 mostly 24th Infantry Division soldiers commanded by a notorious North Korean officer.

Pfc. Wayne “Johnnie” Johnson, one of just 262 survivors from the so-called “Tiger group,” secretly recorded the names of 496 fellow prisoners who died in captivity.

The “Johnnie Johnson list,” which didn’t become public until the 1990s, recorded the date of death for William H. Evans Sr. as Dec. 12, 1950. He was 55.

Three other American civilians were on Johnson’s list — George Hale, an electrical engineer; Patrick Byrnes, a Catholic bishop; and Walter Eltringham, an engineer.

Other civilians who died in the war and were not recovered were Patrick Brennan, Norman Hamm and Joseph Tennant, according to the Hawaii-based DPAA.

The agency has a number for a State Department representative for civilians, along with numbers for the individual branches of service, on its website.

The DPAA initially referred all civilians to that number. However, a spokesman later clarified that Evans and the other three American civilians killed as part of the Tiger group would fall under the Army’s purview.

“Let me be clear that during excavations as part of our search for unaccounted for U.S. service members and [Department of Defense] civilians, DPAA would recover any remains believed to be those of U.S. persons,” Lt. Col. Kenneth Hoffman told Stars and Stripes in an email.

“As such, Family Reference Samples (FRS) would need to be on file” to distinguish the remains, he said, referring the cases to the Army’s service casualty office.

The other three civilians known to the DPAA should start with the State Department, he added.

The search for the 5,300 believed to be in North Korea has been complicated by rising tensions over the communist state’s nuclear weapons program.

ID issues The identification of remains that are returned is also a difficult task that can take years if not decades. Those returned in the past were often co-mingled and in at least one case were found to be animal bones.

The DPAA has received about 630 sets of remains from unilateral turnovers and field recovery missions, Hoffman said, adding that “not all were American remains.”

So far, 339 identifications have been made, “approximately 80 percent of what we believe to be American from those sources,” he said.

Evans said his father’s burial site is known to the government and expressed hope that would make the task of identification simpler.

He has his father’s wallet, tie pin and an Army T-shirt. “My father used a cane often when walking. I understand he had a hip problem,” he added.

Evans hasn’t yet provided DNA as he’s been trying to figure out whom to contact. He also doesn’t know what information his mother may have provided in the 1950s.

William Hobeck Evans had been a well-known society figure who frequently entertained military officers at his home in Seoul, his son said, recounting details he learned from his mother.

“As the rumors of war started to come around more and more, the visits would become more frequent at the house,” he said. “My mother would facetiously say that the whiskey flew quite good at these meetings.”

He doesn’t know what they talked about and has no documentation to prove his father’s connection with the military.

He says his father had lived in Korea since the 1930s and had extensive knowledge about the area. The elder Evans had been born in Japan where his father, originally from Linwood, Pa., settled after finishing his Navy service in 1885.

The North Koreans came to the family’s house after advancing to Seoul at the start of the war and detained Evans, giving him just a few minutes to collect his things.

“So he picked up cans of food and some cigars and he was put onto a truck,” said his son, who was 4 years old at the time.

The rest of the narrative comes from survivors and historical accounts about captives dying of starvation and exposure or being beaten and shot to death as they were forced to march north toward the Chinese border.

“If things turn out the way I hope then at least maybe it would be nice if the government could give some recognition to my dad and others also who died simply because they were U.S. citizens mainly,” Evans said. “They suffered the same situation as the soldiers did when they went to the North.”

gamel.kim@stripes.com Twitter: @kimgamel