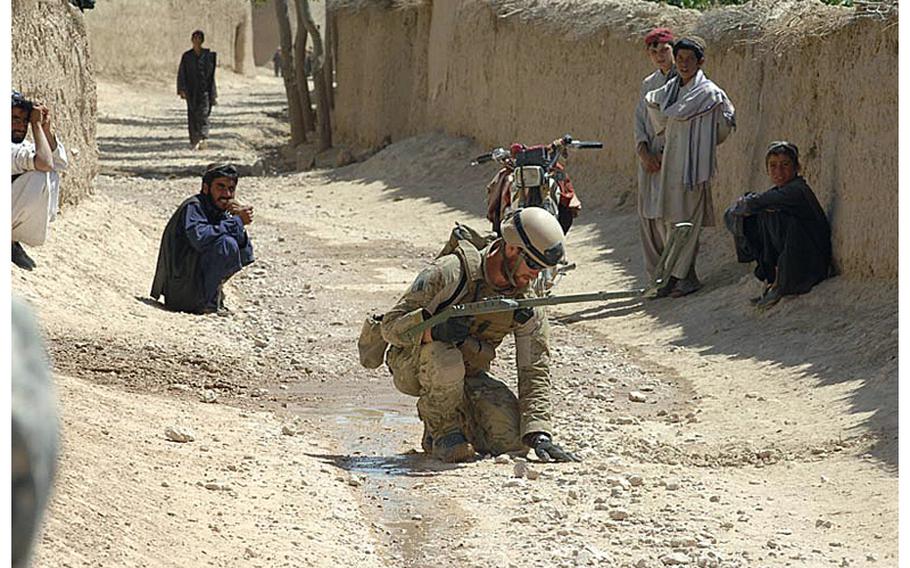

A Navy explosive ordnance disposal technician searches for an IED while locals watch in Zabul Province, Afghanistan in Sept. 2010. Military leaders say the number of bomb disposal experts should remain steady even as the military begins its pull back from Afghanistan. (Seth Robson/Stars and Stripes)

The U.S. will retain much of its capacity for combating IEDs, officials say, even after it withdraws troops from Afghanistan and shrinks its military.

Faced with a defense budget reduction of about $450 billion over 10 years, the military plans to cut more than 100,000 troops from all branches of service. However, officials hope to hold on to most of the capacity that has been built up to dismantle one of the most deadly devices that the U.S. military has faced in the past decade.

Explosive Ordnance Disposal technicians have been heavily involved in recent wars, where an enemy vastly outmatched by America’s conventional forces has resorted to jury-rigged booby traps to extract the maximum blood-price on foreign occupiers.

EOD crews have cleared more than 100,000 IEDs from Iraq and Afghanistan, but the task has been accomplished at great cost: The EOD Memorial at Eglin Air Force Base, Fla., includes the names of 111 servicemembers from all branches killed in action in Iraq and Afghanistan.

As the U.S. prepares to withdraw the bulk of its forces from Afghanistan next year, military planners expect many EOD troops to return to traditional roles clearing mines, bombs and dud shells from Army ranges, plane wrecks and sea lanes. But they are also keen to retain — and even enhance — the nation’s ability to combat the IED.

The prospect of further engagement in the Middle East, with a civil war brewing in Syria and the belief that Iran is pursuing a nuclear bomb, means leaders are well aware of the possibility that U.S. troops could find themselves combating the crude, but deadly, homemade bombs in future conflicts.

Navy Expeditionary Combat Command chief Rear Adm. Michael Tillotson, who oversees Navy EOD, said May 1 that the service — which has added 231 people and eight EOD platoons in the last 10 years — has no plans to shrink its force of 1,670 EOD sailors.

“All of the U.S.’ potential adversaries have learned that the insurgency type of campaign waged against the U.S. has been successful,” Tillotson said. “As we move into the future, there will be nonstate terrorist organizations trying to influence things. I think we, the U.S., need to … maintain our ability to counter IEDs.”

For Navy EOD personnel, the Global War on Terrorism has meant more time humping across the mountains of Afghanistan and sands of Iraq to help ground troops battle IEDs, and less time swimming underwater to disable sea mines or floating on aircraft carriers to deal with bombs that have come loose on returning bombers.

As a result of those wartime operations, only four Navy EOD platoons have focused on countermine efforts in recent years.

But after the Afghan War ends, the Navy plans to increase the number of platoons to 12 with a goal of 18 countermine Navy EOD teams, Tillotson said.

And he said he expects there will be excess future demand for EOD services that the Navy won’t be able to meet.

“I don’t see the IED going away,” he said.

Col. Stephanie Holcombe, a spokesperson for the Joint IED Defeat Organization, an interservice effort to win the battle against IEDs in Iraq and Afghanistan by developing and fielding new equipment, noted that there are more than 600 IEDs, or caches of IED-making materials, found monthly in parts of the world other than Iraq or Afghanistan.

Col. Dick Larry, a Pentagon officer who oversees Army efforts to combat IEDs, said the service has almost tripled the number of EOD soldiers — from 900 to 2,400 — in the past decade.

The Army plans to cut 80,000 troops over the next few years, but there are no plans so far for fewer EOD soldiers, he said, adding that many Army EOD personnel are expected to go back to clearing ranges and helping police deal with explosives.

EOD personnels’ knowledge of fusing and firing systems and understanding explosives and weapons gave them a jump-start on dealing with IEDs when they started to proliferate in Iraq and Afghanistan, he said. What people weren’t prepared for was the sheer scale of the problem.

“None of us had the sense of the number of IEDs we were going to encounter when we went into Iraq, but because of the prior knowledge we had, it helped us to not get too far behind as we started encountering more,” Larry said.

The Air Force has no plans to cut its 1,300 EOD personnel, but it didn’t expand its force during the current wars. In the past decade, Air Force EOD has conducted 40,000 missions in Iraq and thousands more in Afghanistan, according to Maj. Landon Phillips, 35, of Jasper, Tenn., the Air Force EOD program director at the Pentagon.

“Our guys go where the mission is, so if they need us on top of a mountain or in the desert, our guys are going to be supporting other services,” Phillips said, adding that he’s lived in a tent on the side of a mountain and in old buildings in Baghdad on recent deployments.

On the battlefield, there is a certain swagger about many EOD personnel, whose jobs were featured in the Oscar-winning Hollywood film “The Hurt Locker.”

A servicemember wearing the EOD badge has credibility, whatever their branch of service, Phillips said.

“Commanders see that he is an EOD guy, and he’s going to get my soldiers, SEALs or Marines something they want,” he said. “They don’t see your service. That EOD badge is really respected.”

Chief Master Sgt. Jim Brewster, 47, of Lockbourne, Ohio — the Air Force’s EOD career field manager — said most EOD personnel are modest except when they are on the job.

“When they are doing their job, it is not a time to be modest,” he said. “It is a time to be confident. They know it is a hazardous job, and they have to keep focused on it. It is about saving lives, and I think they have saved countless lives.”

The Air Force is striving to embed lessons learned from the battle against IEDs into EOD training, Brewster said.

Air Force EOD plans to refocus on its traditional roles — the most important of which is responding to accidents involving the Air Force’s nuclear weapons, Phillips said.

Air Force EOD also deals with aircraft that have ammunition come loose in flight, and they clear explosive debris from ranges and crashed military planes. If airfields are attacked, EOD is trained to go out and identify unexploded munitions and help engineers get the facility back on line, Phillips said.

The Marine Corps appears to be the only service with plans to trim its EOD force, but even then, the numbers are minimal. The current force of 800 is double the number 10 years ago, officials say, with plans to cut only 50 positions over the next three years.