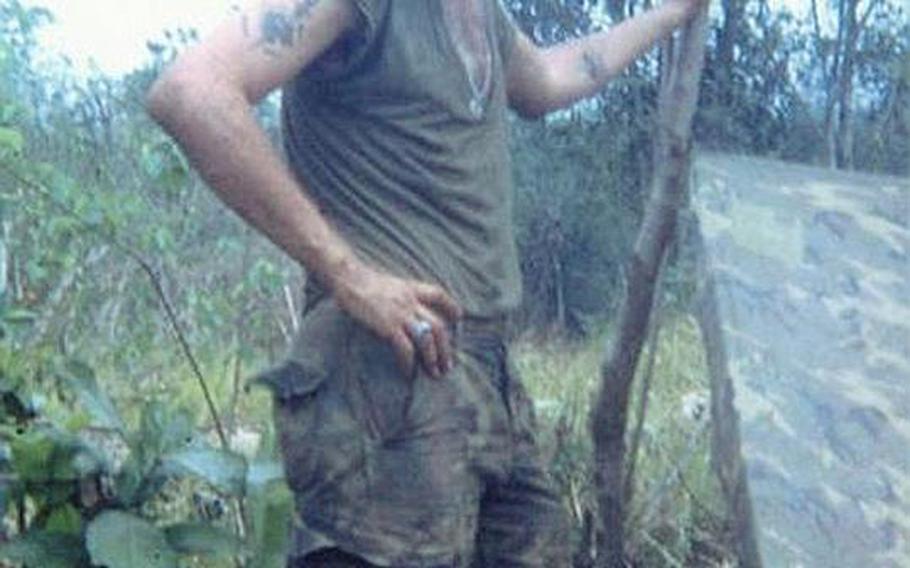

Charles Trumpower served with the Marine Corps in Vietnam in 1969 and now speaks to veterans across the country about post-traumatic stress disorder. (Charles Trumpower/Courtesy photo)

The anger burns inside Niko Lorris.

It chewed through five marriages and alienated his children. Most days, it keeps the 64-year-old veteran bunkered in his Florida home.

“I can’t deal with people,” said Lorris, who is disabled with post-traumatic stress disorder from his 1966 Army service in Vietnam. “I’ve got so much anger in me.”

Two years ago, he had two heart attacks.

New research might determine whether all that rage — a symptom from his trauma for more than four decades — might also have played a part in Lorris’ heart problems.

For the first time, researchers at the Department of Veterans Affairs are taking a comprehensive look at the long-term effects of PTSD and its connection to other serious health issues that develop decades after military service ends.

The disorder is caused by traumatic events such as warfare, sexual assault and vehicle accidents and marked by persistent fear, confusion or anger. Past research suggests it can surface long after the trauma occurs and is related to problems such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, asthma and diabetes, according to the VA.

Vietnam veterans are the largest group of PTSD patients in the United States, and as more reach their 60s, they could provide the clearest evidence yet of a relationship between trauma on the battlefield and a variety of health problems much later in life, said Matthew Friedman, executive director of the National Center on Post-traumatic Stress Disorder.

Studies on tap

They are the subject of three upcoming PTSD studies — the strongest push by the VA since the mid-1980s to understand the disorder in Vietnam veterans — that are expected to be completed in the next few years, according to the VA and the Government Accountability Office.

“If you continue to smoke, you are more likely to have heart disease, lung cancer and other kinds of things. We couldn’t make that statement if we didn’t have the longitudinal data,” Friedman said.

The VA’s new research could lead to similar broad pronouncements about trauma and “help us understand what is in store for our newest veterans if we can’t help them get over their PTSD,” he said.

It is estimated that 180,000 to 324,000 of the more than 1.8 million who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan will experience post-traumatic stress disorder, according to the VA.

New data will help the VA plan for the care and treatment of those veterans, Friedman said.

“We can prepare for the consequences, whether they are psychiatric or medical,” he said.

One study will tap a cross-section of Vietnam vets first examined in the 1980s as part of the landmark National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, which still accounts for much of the scientific knowledge on the long-term effects of PTSD.

The earlier research found that about 30 percent of veterans had experienced the disorder at some point since the war. That shocked lawmakers at the time and led to wider recognition of the disorder, including beefed-up VA funding and the creation of the National Center on PTSD, Friedman said.

The new effort, called the National Vietnam Veterans Longitudinal Study, could have a similar impact and spur new policies when it is completed in 2013, Friedman said.

“Who got better, or are there new cases?” he said. “Also, what are the consequences of having PTSD most of your life?”

The study will collect data from veterans like Tom Allen, 62, of Greensboro, Ga., who served as a Navy corpsman in Vietnam.

His PTSD intensified after a series of events in 1998 — a vehicle crash, missed work and the death of his mother.

“It was all downhill from there,” he said.

The VA recognized his disability in 2001, Allen said.

The PTSD makes him unable to work and causes night terrors he calls the “red dream,” a replay of a long-ago mission in Vietnam that led to the decimation of his unit.

His violent nighttime thrashing and deteriorating mental health led to the end of his marriage last year. Allen said he now takes three medicines to sleep at night.

“I would swing around and hit the person next to me, who was my wife,” he said. “We were married 16 years, and I was calling her a Viet Cong.”

Meanwhile, two other VA studies will examine how twins and women who served during Vietnam are faring with PTSD.

The VA keeps a registry of 7,369 twins who both served. The researchers are interested in whether twin men with the same DNA have been affected differently over the years by combat trauma.

Differences and similarities could point to the influences of DNA in the long-term development of PTSD, said Kathryn Magruder, a research health scientist at the VA Medical Center in Charleston, S.C.

Women did not serve in combat during the Vietnam War but many experienced trauma while serving as nurses and care providers to the wounded returning from battlefield, Magruder said.

“No one has studied the mental health of these women,” she said. “Their experiences were certainly different than the men, but they had other experiences. Some of these women were the last people to hold the hand of an 18-year-old kid who was dying.”

Backlog of cases

The new wave of research comes as the VA struggles to handle a backlog of claims generated by two current wars and an aging veteran population, many of whom served in the Vietnam War.

There are about 386,000 veterans collecting compensation for PTSD -- 247,486 of those are Vietnam veterans, the VA reported in 2009.

The agency, for about a decade, put off its main study of PTSD among Vietnam veterans — the National Vietnam Veterans Longitudinal Study — despite a mandate by Congress to follow up on the 1988 research, according to a GAO analysis in May.

An attempt to conduct the research in 2001 was aborted early on, and the VA inspector general later found the agency did not properly plan or administer the study contract, the GAO reported.

Now, after months of congressional hearings, the VA appears ready to begin the study this summer, said Tom Berger, executive director of the Veterans Health Council, a division of the Vietnam Veterans of America.

“We have been leading the charge to make sure they obey Congress’ mandate,” he said.

When the VA researchers talk with Vietnam veterans, it likely will find that PTSD causes heart disease, affects the immune system and leads to other serious health consequences, Berger said, findings he believes could lead to a renewed effort to get treatment for all veterans.

“It is one of the most important studies ever for the mental health of our troops,” he said.

Charles Trumpower, 64, of Milford, Conn., is a disabled Marine who served in Vietnam in 1969 and now travels the country speaking to veterans about his PTSD.

He said the VA will also discover little has changed in the 35 years since Saigon fell.

Many veterans traumatized during the Vietnam War are still resentful of a public they believe abandoned them, distrustful of the VA system charged with caring for them, and dependent on each other for support, Trumpower said.

“The stories haven’t changed,” he said. “There are still a lot of issues and a lot of anger.”