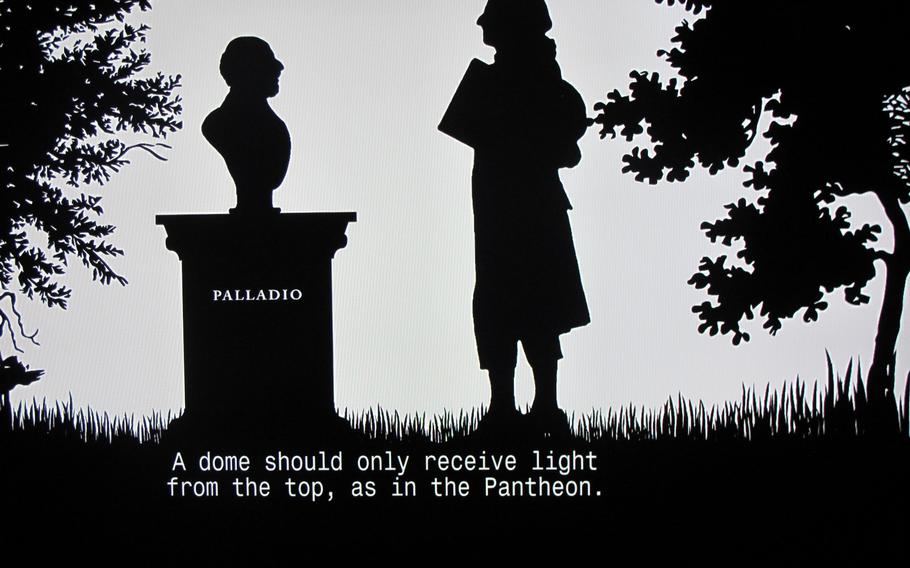

An art exhibition at the Palladio Museum in Vicenza, Italy, about Thomas Jefferson and Andrea Palladio features an imaginary discussion between the two. Palladio is a little miffed that Jefferson never visited the Veneto region to see his works, and questions Jefferson's use of bay windows at Monticello. "It's just that I wanted more light," Jefferson replies in the next scene. (Nancy Montgomery/Stars and Stripes)

Americans can immerse themselves in a founding father’s genius at an art exhibition dedicated to the idea that all architects are not created equal. Many make great buildings. Only a few change the world.

Among the few are Thomas Jefferson and Andrea Palladio. The exhibition, “Jefferson and Palladio: Constructing a New World,” explores Jefferson’s relationship with the works and ideas of the 16th-century Renaissance man whose influence is vast and pervasive in American public architecture. But you’ll have to hurry; the exhibit ends March 28, a week from Monday.

It’s a multimedia show featuring Jefferson’s notes and architectural drawings, building models, photography, sculpture, film and talking heads in the form of an imaginary discussion between Jefferson and Palladio.

The exhibition is curated in English and Italian. It is at Vicenza’s Palladio Museum, in a palazzo designed by Palladio. His buildings, nearly all located in Vicenza, garnered the city designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Palladio’s ideas traveled the world and the centuries through the architect’s treatise, “I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura,” or the Four Books of Architecture. Jefferson referred to the books as his “bible.” He based designs for the University of Virginia and the Virginia State Capitol on Palladian principles. Those are generally described as being based on symmetry and perspective, and inspired by ancient Greek and Roman temple architecture.

Palladio’s Villa La Rotonda, a mansion located on a hill just outside Vicenza, was the model for Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation home outside of Charlottesville, Va. Monticello means “small hill” in Italian. The house is depicted on the nickel.

If Monticello, the home of the author of the Declaration of Independence, was a self-portrait of Jefferson’s polymath genius, it was also something else. “It even tells us of its crueler side: almost 100 slaves lived and worked at Monticello,” the exhibit notes.

Jefferson shaped the U.S. more than anyone else through art, architecture and the grid system he devised to divide up territory, the exhibit says. A man of the Enlightenment, he sought to build a new world on reason and beauty. “To pursue this aim, he looked to his own time but also to the past,” the exhibit says, “to ancient Roman civilization and the architect who translated it for the modern age: Palladio.”

DIRECTIONS: Address: Palladio Museum, Palazzo Barbarano, Contra ‘Porti, 11, 36100 Vicenza. By train: take the Venice-Milan line to the station of Vicenza and then walk 10 minutes. By car: from Milan, Motorway A4, exit Vicenza Ovest; from Venice, Motorway A4, exit Vicenza Est; the nearest car parks are Park Verdi in Viale Verdi; Park Fogazzaro in Contra’ San Biagio; Park Santa Corona in Contra’ Canove Vecchie; Park Matteotti, Piazza Matteotti.

TIMES: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday to Sunday through March 28.

COSTS: Tickets cost 10 euros, but there are discounts for students, people over 60, groups and families. No charge for children under 6, disabled people and members of the Italian armed forces.

FOOD: Numerous eateries are nearby.