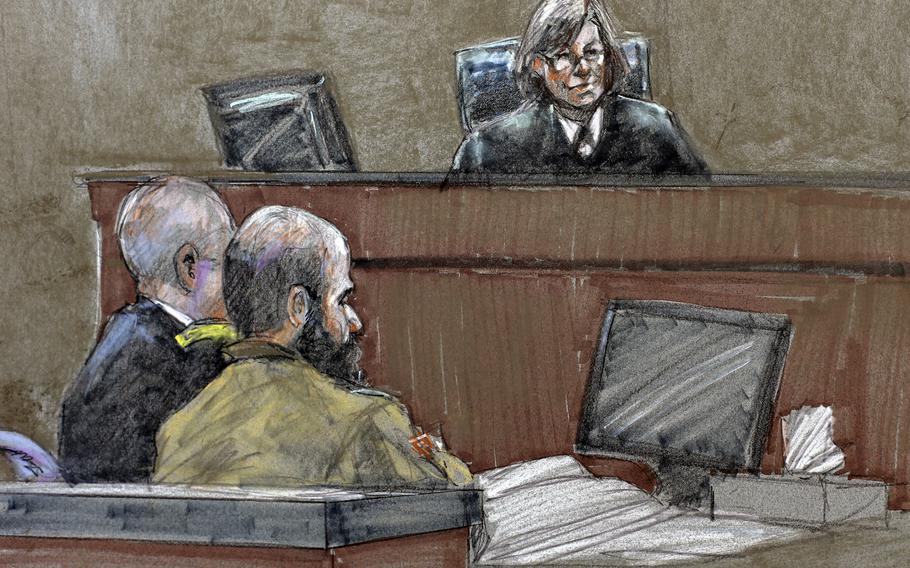

In this August, 2013 courtroom sketch, Maj. Nidal Hasan, center, sits before the judge, U.S. Army Col. Tara Osborn, at the Lawrence William Judicial Center during the sentencing phase of his trial in Fort Hood, Texas. (Brigitte Woosley)

FORT HOOD, Texas — While Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan was sentenced to death Wednesday, it could be years before he faces execution by lethal injection — if ever. Still, former military lawyers say the court-martial shows that the military justice system works.

A panel of 13 officers deliberated for more than two hours before sentencing Hasan for the 2009 mass shooting that killed 13 soldiers and wounded 31 others at Fort Hood. Hasan did not react to the sentence, which included forfeiture of all pay and dismissal from the service.

The convening authority, Maj. Gen. Anthony Ierardi, must still approve the sentence, and then the Army Court of Criminal Appeals and the Court of Military Appeals will automatically review the case. After the appeals process is complete, the president must approve the sentence before Hasan is executed.

Hasan, who represented himself, could choose to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. But despite the many unusual aspects of the case, the former military lawyers said there isn’t much that should create problems during the appeals process.

The most common grounds for appeals in capital cases are inadequate representation and problems with discovery — for example, if the prosecution did not allow the defense access to all the evidence the prosecution presented, said retired Maj. Gen. John Altenburg Jr., who served as deputy judge advocate general of the Army and now practices law in Washington, D.C. But the Supreme Court has said that while there is a constitutional right to defend oneself, choosing to do so means one cannot appeal on the grounds of inadequate representation, several lawyers said.

Geoffrey Corn, a retired military attorney and current law professor at South Texas College of Law, said there are a few issues that could be raised on appeal, but he doesn’t believe any of them will be successful in this case. Still, he said, the case that established the right of a defendant to represent himself was not a capital case, so if the Supreme Court wanted to carve out an exception, “they will never have a better opportunity than this.”

“I think the only risk to this case … is that an appellate court will say, ‘We don’t like the law, so we’re going to change it,’” Corn said.

Because of the trauma and carnage that Hasan inflicted on the victims and their families, Corn said, “I think the outcome was inevitable.” But the way it played out is “a testimony to the credibility of our system.”

Everyone in the process, from the police officer who brought Hasan down and then began working to save his life, to the doctors who saved his life at the hospital, to the standby defense counsel who tried to represent his interests to the judge who protected his constitutional rights, “everyone in that process has demonstrated the victory of reason over power … of humanity over depravity,” Corn said.

Many people, including some of the family members, have expressed disgust and frustration at how long the court-martial process took, but Corn said it took time because it was methodical, not because of a lack of due diligence.

“What it teaches us all is powerful, and that is: How we treat the worst of us is really a reflection of the best of us,” Corn said. “He was just a beneficiary of rules that exist to protect all of us. … We get the right outcome, but we can respect it, because it was done right.”

‘It may be that he simply doesn’t care’

The court-martial began Aug. 6, moving quickly through dozens of witnesses who were in the medical Soldier Readiness Processing center when Hasan stood up, shouted, “God is greatest” in Arabic, and opened fire with a semi-automatic pistol.

Testimony slowed as prosecutors called medical examiners and crime-scene investigators and admitted more than 200 shell casings and several ammunition magazines into evidence. But throughout the trial, Hasan sat passively in his wheelchair, rarely asking questions or raising an objection.

Hasan, a psychiatrist, did not call any witnesses or make a statement on his own behalf. He submitted very little evidence — only basic biographical information and the results of one of his annual officer evaluations. He opened the court-martial in what seemed like an admission of guilt: “The evidence will clearly show that I am the shooter.”

But Hasan asked the judge, Col. Tara Osborn, not to tell the jury he had originally tried to plead guilty. Under military law, the accused in a capital case cannot plead guilty.

Greg Rinckey, a former military attorney and current managing partner of the law firm Tully Rinckey, said that if he was representing Hasan, he would have wanted the jurors to know about the plea attempt, because it could have shown he was responsible for his actions.

But Corn said Hasan likely would not have ever actually entered a guilty plea because he did not seem to think he was actually guilty of a crime.

Hasan had wanted to use a “defense of others” strategy: to tell the jury he killed the soldiers who were preparing to deploy in an effort to save Taliban leaders in Afghanistan. He fired the defense attorneys who had been assigned to him when they refused to move forward with the plan, and the judge later said he could not use the defense.

During a session in which the jury was not present, Hasan told the judge that his motivation for the shooting was that “these were deploying soldiers that were going to engage in an illegal war.” And, when the judge first asked Hasan if he wanted her to tell the jury he had tried to plead guilty, lead prosecutor Col. Mike Mulligan said Hasan would not have pleaded guilty because he did not have a “culpable state of mind,” Corn said.

Hasan agreed, saying that while the trial is supposed to be an adversarial process, he thought Mulligan had explained the situation well.

Some of Hasan’s actions could also be interpreted as attempts to “build air into the record,” to make the case look so unusual that the sentence simply could not stand, Altenburg said.

“That’s if he doesn’t want to be a martyr. … But on the other extreme, it may be that he simply doesn’t care,” and didn’t want to make any effort to thwart the death penalty, Altenburg said.

Still, appellate courts will be very protective, because “death is different,” Rinckey said. “They want to make sure that the process is fair.”

The last time the military put a servicemember to death was April 13, 1961.

hlad.jennifer@stripes.com Twitter: @jhlad