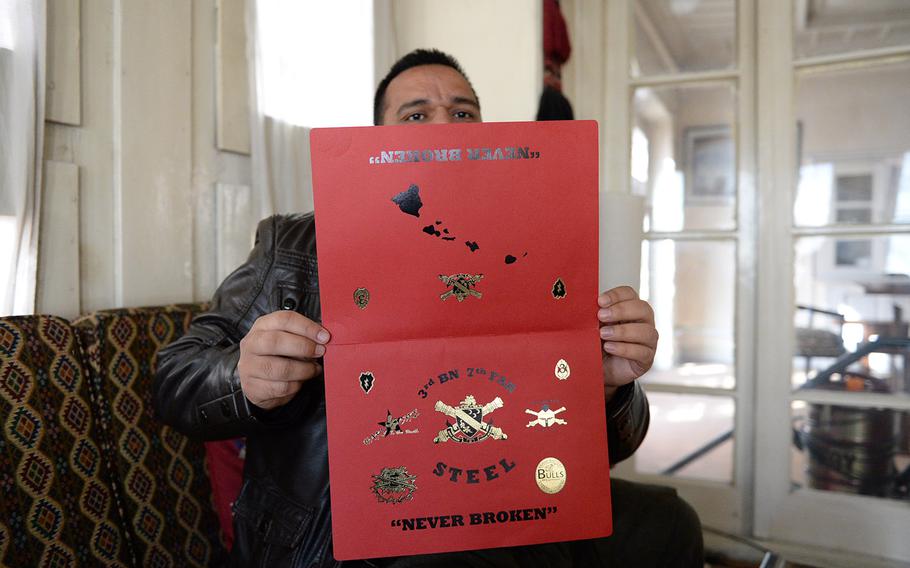

"Zakir," a former interpreter for the U.S. military in Afghanistan holds an award he received from a unit with whom he worked during an interview in Kabul. He fears showing his face because of Taliban threats he received. Like many former interpreters, he's been waiting for years to receive a Special Immigrant Visa in order to immigrate to the U.S. (Heath Druzin/Stars and Stripes)

KABUL, Afghanistan — Naqueebullah Malikzada reminisced wistfully about his youthful days in Helmand province, sleeping in foxholes alongside American soldiers, hunting Taliban and fighting through ambushes.

He scrolled through photos spanning more than a decade at war. There he was in desert fatigues carrying an AK-47 with American soldiers, there he was manning a .50 caliber machine gun, there was the leg of a suicide bomber who carried out an attack that narrowly missed killing Malikzada. In the early photos, he has a youthful grin — an 18-year-old emerging from boyhood on a great adventure.

It was a time of peril, but purpose: He was helping build a better Afghanistan, one where he had a promising future.

These days, after working as a translator for the U.S. military for more than 10 years, the danger remains but his hope has faded.

Malikzada’s weary eyes darted to the entrance of his bare-walled room with every bump or slam of a door. The carefree smile has been replaced by a taut face and hard stare, his jaw clenched with worry that he is losing the ability to protect his family. His dream of a life in a peaceful Afghanistan has been buried by night letters, beatings and ominous phone calls. The only future he sees now is the chance to move to the United States on a Special Immigrant Visa, which was created for former U.S. military and government interpreters in Afghanistan and Iraq who face threats. It’s a promise unfulfilled for Malikzada and thousands like him who fear the Taliban will arrive before their visas.

“If they catch you, they kill you,” said Malikzada, now 31 with a wife and two young children.

He has been waiting five years for his visa,and Taliban threats against him and his family have grown.

Thousands of former U.S. interpreters are in the same potentially deadly limbo. Many are fighting denials issued for reasons ranging from mysterious security red flags to disputed claims by government contractors that the interpreters were fired for misconduct. Some whose applications were denied received no explanation at all.

This problem persists despite congressional hearings and high-profile calls for changes to the visa system.

The State Department is currently processing 10,000 Afghan applications for 7,000 remaining slots and the program is slated to end on Dec. 31, despite the U.S. continuing to recruit and employ translators for a military mission that keeps getting extended. Those limits rankle advocates for more aggressively resettling interpreters.

“This program should not have an arbitrary timeline on it,” said Ryan Crocker, a former ambassador to both Iraq and Afghanistan who oversaw the start of the Special Immigrant Visa program.

In interviews with a dozen former and current interpreters, some in Afghanistan and some who made it to the U.S. after long waits, a pattern emerged: years of service, mounting threats and mysterious visa denials. Advocates say denying interpreters safe passage to the U.S. is a betrayal of trust and a potential death sentence.

“There’s no Taliban or Daesh amnesty program,” said Matt Zeller, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer who founded No One Left Behind, a nonprofit that works to settle former interpreters in America. Daesh is a shorthand for the Islamic State.

'The Taliban are back'

Malikzada has a recurring dream: There’s a knock on his bedroom door. It’s his mother. “Wake up, wake up, the Taliban is back in power in Afghanistan.”

Each time, he awakens with a gasp.

“I wake up, take a deep breath, say thanks God, do a check of the house and go back to sleep,” he said. He never sleeps in the same house more than a few nights in a row Instead, he rotates among several homes in Kabul throughout the week with his family. The couple sleeps in shifts and Malikzada always makes sure to cover his face when he’s in public in case someone he ran into in his long service with the U.S. military recognizes him.

Like many interpreters, Malikzada speaks a breezy English picked up from the troops with whom he worked. “Bro” and “dude” pepper his speech, and he slings slang like a twentysomething American.

In his lengthy tenure with U.S. forces in some of the most dangerous parts of Afghanistan, he stood side by side with American troops during frequent firefights, shooting at insurgents with the Kalashnikov that his comrades entrusted to him. He saw friends killed and had his own close calls, including a roadside bomb that left him in a coma for 24 hours. He was back on patrol in a few days. It wasn’t until he believed his family was in the crosshairs that he gave up on Afghanistan.

An Afghan National Army officer sympathetic to the Taliban who worked at the same coalition base as Malikzada talked openly about killing American soldiers. When Malikzada reported the talk, the officer tried to follow him home from base one day. Malikzada was able to evade him, but he was spooked.

Then the phone calls started. They were chillingly formulaic — a man saying he knew who Malikzada worked for and promising to cut off his head.

Malikzada applied for a Special Immigrant Visa in 2011. He’s been waiting ever since.

In the fall, Malikzada’s father went to Bagram province to check on family orchards. Masked men beat him so badly they broke his arm. They mentioned Malikzada’s work with Americans and said if the family returned they would be killed.

Aside from the specific threats, Malikzada and other interpreters worry that detained insurgents — many of whom are back on the street after serving their time or through numerous jailbreaks — will recognize them and exact revenge.

In September, when the Taliban took over the northern city of Kunduz and emptied the city’s two prisons during their two-week occupation, fear rippled through the interpreter community.

“I teach everyone in my home: If someone asks you guys, tell them there is no Ehsan here,” said former interpreter Ehsan, who has been waiting four years for his visa and asked to be referred to by his first name because of ongoing threats.

An incident in October increased Malikzada’s desperation to leave. His 16-year-old brother was walking home from prayers when four men attacked and pistol-whipped him, demanding that he tell them where Malikzada lived. His brother stayed silent and the beating sent him to the emergency room with deep cuts in his scalp.

Even in relatively safe Kabul, it became was becoming hard to hide.

So Malikzada sold his car and his wife’s and mother’s jewelry to pay for his brother to make the perilous journey through Iran and Turkey and then onto a smuggler’s boat bound for Greece. Nearly 8,000 asylum seekers have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea since 2014, according to the International Organization for Migration, and yet Malikzada says if he had enough money he would take his family across the sea to escape what he sees as certain death in Afghanistan.

“It’s better to accept the risk than to wait here every day, because every minute we are under dire threat,” he said.

Malikzada’s brother is in Berlin awaiting word on asylum.

'I feel like I'm dead'

For former interpreters, the excruciating wait and mysterious denials are frustrating and heartbreaking. Siddiq, who worked for U.S. forces for three years and also asked to be referred to by his first name, says he lives like a prisoner in his home outside of Kabul, afraid he will be recognized if he ventures outside.

He has been trying to get a visa for four years and recently reapplied after getting a denial. He said the betrayal and fear has made him consider suicide.

“When they denied me (a visa), I didn’t eat for weeks, it’s really painful,” he said. “I feel like I’m dead.”

The Special Immigrant Visa program is run by the State Department, but an alphabet soup of government agencies combs over interpreter names during security vetting, and watch lists often include common Afghan names that are the equivalent of “John Smith.”

State has, at times, has been openly hostile to the program, as evidenced by a 2010 cable obtained by The Associated Press in which then-U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Karl Eikenberry wrote to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, objecting to the program and proposing that rules be changed to make it more difficult for interpreters to get visas.

“This act could drain this country of our very best civilian and military partners: our Afghan employees,” Eikenberry wrote. “If we are not careful the SIV (Special Immigrant Visa) program will have a significant deleterious impact on staffing and morale, as well as undermining our overall mission in Afghanistan. Local staff are not easily replenished in a society at 28 percent literacy.”

A senior State Department official with oversight of the visa program said that her office is committed to giving visas to all who qualify in a timely manner, but that security considerations can mean a long wait. She said that despite delays, the U.S. has issued more than 20,000 visas for interpreters and family members from Iraq and Afghanistan in the past 2½ years.

“I think there’s a real understanding based on personal knowledge of what these folks did for us, and that we really do owe them a lot, and the best thing we can do is follow through on the promise that we made to, if they qualify, to get them out of harm’s way, to get them to the United States,” said the official, who would only speak on background due to State Department rules. “Our main struggle is always facilitating legitimate travel, which this is, and keeping our borders secure, and we have to put people through an interagency clearance process.”

Everyone involved in the visa process, including the myriad agencies doing security checks, need to prioritize the program and the White House should pressure them to step up, said Crocker, now the dean of Texas A&M’s George Bush School of Government & Public Service and an advisor to No One Left Behind.

“It has not been nearly as effective as it need to be,” he said. “The wait times for SIV procedures are extraordinary — well over a year — and that’s a year in which an interpreter or someone else eligible for their service to us can get killed and they do.”

'These aren't our enemies'

In Malikzada’s case, he got a vague message that his name had been “red-flagged,” a common fate for interpreters applying to the program.

Army Lt. Col. Woody Woodring, who worked with Malikzada in the Taliban heartland of Helmand province and has helped two other interpreters get to the U.S., said every Afghan who worked with him there knew they would be beheaded if they were caught.

“If there’s any whiff that they helped Americans, they’re automatically executed,” he said. “I don’t think you could get a much more dangerous situation than what we were in in Helmand.”

An alphabet soup of government agencies combs over interpreter names, and watch lists often include common Afghan names that are the equivalent of “John Smith.” The irony for Malikzada is that, desperate to support his family, he recently reapplied to interpret for American forces and despite the State Department red flag, he was accepted and now works on a military base.

“I’m kind of confused because, honestly, I worked with the U.S. government,” he said. “It’s kind of hurting my feelings.”

Asked if there have been any cases of visa applicants found to be a legitimate security threat or engaging in terrorist activities, the official declined to be specific.

“I think there are cases where it’s just not clear ... and in that case we’re going to err on the side of national security,” she said.

Some interpreters trace their problems to a company called Mission Essential (formerly Mission Essential Personnel) that the U.S. government contracted to hire and manage interpreters. Some say they were let go under false pretenses after being told they failed a polygraph or security questions, while others say their departures were mischaracterized in Mission Essential paperwork.

Mission Essential did not respond to several requests for comment.

A requirement of the Special Immigrant Visa program is “faithful and valuable service,” and anyone who was fired or deemed to have gone “absent without leave” is disqualified.

The State Department official said while the reasons for termination in some cases seem minor, small transgressions can be magnified in a war zone, eroding trust. She said the department can only accept or deny interpreters based on their visa qualifications, rather than determining the fairness of past decisions.

“I would say many of these decisions were made for the right reasons, even if they seem like minor reasons,” she said. “We’re not going to go revisiting personnel decisions from several years ago.”

With U.S. troops still in harm’s way in Iraq and Afghanistan and the potential for other conflicts in the near future, locals with think twice before helping Americans if they see their predecessors abandoned, Crocker said.

“I think that it is a profound moral obligation,” he said. “There’s also a practical convention to it. Everybody around the world watches what we Americans do. We are going to have other contingencies in other countries elsewhere and we will need interpreters.”

Zeller, who started No One Left Behind after his interpreter faced threats for saving his life in a firefight by killing two approaching insurgents, said abandoning interpreters is more than an ethical failure. As groups like the Taliban and the Islamic State target them and broadcast their deaths, it could imperil U.S. soldiers on combat missions.

“How can we reasonably expect the local population to stand up and support us when they’ve seen these videos and know service to Americans is a death sentence?” he said.

The National Defense Authorization Act of 2016 added 3,000 Special Immigrant Visas for Afghan interpreters (their family members don’t count against this). The program is set to expire at the end of the year, despite no end in sight to the U.S. mission in Afghanistan. Zeller, whose group has helped resettle more than 1,500 interpreters and family members, says the current cap is several thousand short of the number of qualifying interpreters.

“These aren’t our enemies, they’re our allies, they’re our friends and we made a promise to them,” Zeller said. “I see this as a matter of national security. The cost of honoring our commitment is minuscule in comparison to the cost to our reputation if we fail to do it.”