()

RUSKIN, Fla. – She sat on the screened back porch overlooking the river, working to sounds off the breeze: flags flapping, water lapping and the plinking of a wind chime made out of dog tags.

She chatted between taking phone calls and greeting visitors who wander into this unexpected place of respite. Some offer help. Others seek it.

And when the tears flowed, even now after so much time, she allowed them their due.

This small property at the end of an overgrown country road is a place of solace, dedicated to the memory of her late son, Army Spc. Corey Kowall, and the suffering of servicemembers and their families. It is a work in progress built on grief and on healing and on a desire to continue the legacy of serving.

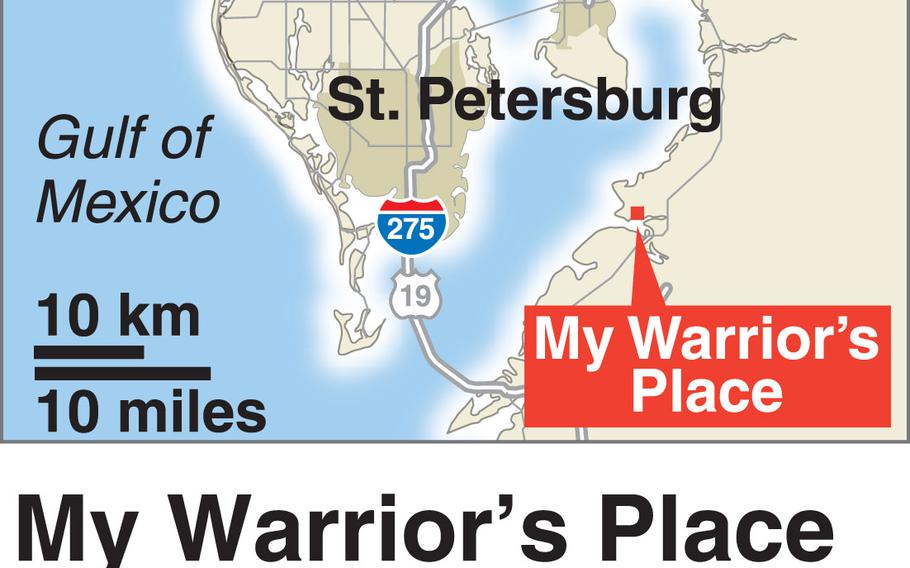

Kelly Kowall created My Warrior’s Place as a refuge for anyone who has served, to come and take out a boat or throw in a fishing line or just sit quietly and look out at the water — no questions asked.

From the driveway, the four brightly painted manufactured homes, two small houses and four RVs in varying states of disrepair could be mistaken for a trailer park. But walk to edge of the Little Manatee River at the front of the 1.7-acre property — with the bronze statue of military boots and rifle, memorial plaques, flowers and flags — and it is clear that something else is going on here.

The dream of a short life

From the time he was 5 years old in Murfreesboro, Tenn., Corey Kowall’s dream was to be an airborne Ranger. He was going to join the Army and jump out of planes.

He loved everything military. He decorated his room with military memorabilia, soaked up war history and would sit for hours listening to veterans’ stories — much to their delight.

At 10, he joined the Civil Air Patrol to learn how to fly. When he was 16, he took his mother flying with him.

Corey piloted, his instructor beside him with his own controls. And his mother sat white-knuckled and silent in the back seat as her teenager flew six touch-and-gos at regional airports before landing back at base.

By 17, her boy couldn’t wait anymore. He went to summer school so he could graduate early and finally join up.

He did basic training. He went to airborne school and got his paratrooper wings, joining the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment in the fourth brigade combat team of the Army 82nd Airborne Division based at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. He tried going straight to Ranger school but was too sleep-deprived to complete the course the first time and got injured the second time when he fell through weak ice.

He was going to try again when he got back from his first deployment.

But one month into his 2009 tour in Afghanistan, Corey was in the turret of a truck when the vehicle swerved to avoid what looked like a buried bomb.

The truck overturned, killing him almost instantly, his mother said.

She had spoken to him three days earlier when he called for her birthday. “Mom, I’m not going to lie to you,” he told her. “It’s pretty dicey here.”

But if it was his turn, he told her, he hoped he could go fighting for his country.

“He only lived 20 years, but as a mother, I got watch him achieve his dream,” his mother says. “I just kind of see him as a rocket that just shot straight up and burst into these beautiful fireworks.”

The healing water

Corey and his mother shared a love of the water. They’d go on boat rides and learned to scuba dive together.

After his death in September 2009, on her way to a grief counselor, she drove by a “Boat for Sale” sign and thought how great it would be to be able to afford that. The water was so healing.

For the next five nights, she dreamed that Corey was telling her to buy the boat and share it with military families.

Finally she called about it. The man wanted $7,000. She had less than $2,500. She was about to hang up, she said, when he asked her why she wanted the boat, and when he heard her answer, he sold it to her for $2,000.

He was a veteran.

Kowall made good on her vision. She created a small nonprofit, brought on board members and local sponsors and started taking veterans out on free boat rides. It did her as much good as it did them.

It struck her that the veterans — in particular the younger ones — were reeling with grief. They were transitioning to civilian lives unprepared, she said. They were losing a strong brotherhood, losing a sense of mission, losing their jobs, their identities, their homes -- all at once.

“Any counselor will tell you that (losing) any one of them by themselves can be devastating,” she said. “So it is any wonder our veterans are struggling when they get out?”

She wasn’t looking to take on a bigger project. “I just wanted to do my little boating trips. It was easy. I wanted to be able to refer them to a program.”

But her searches for programs came up empty.

She called Darcie Sims, a grief counselor she’d met after Corey died. Sims didn’t know of any grief programs for new veterans either.

“So what are you going to do about it?” Sims asked.

Kowall did what she always did when things weren’t sitting right: She took her boat out to nearby Beer Can Island, where she used to take Corey to search for shark teeth. She paced the half-mile perimeter while silently negotiating with God and her son.

“I am walking around going, ‘If this is what you wanted me to do from the beginning, why did you have me do the boat?’” she said. But maybe she had to do the boat to see the next step – and be prepared to take it.

By the third loop, she was cutting a deal. “OK, Corey. I got it. If this is what you want me to do, then OK. But I need a sign. You give me a burning bush sign, and I will do it.”

As she tells it, within seconds a wave washed up, depositing a misfired bullet cartridge at her feet.

She returned home and called Sims. “I need to know you will help me with this program,” she said.

Sims was in. So was her husband, a veteran. They were going to create a grief program for servicemembers. It took them more than a year to create the program and at the end of 2011, they filed the paperwork for a new nonprofit and brought in additional board members. They envisioned a meeting place — somewhere veterans could come to that was safe and devoid of judgment. So, with less than $500 to her name, Kowall began scouring local real estate.

A haven for squatters

Once she set her mind to it, things moved quickly.

A commercial property at $250,000 was already sold. But the owner had another property. It was waterfront and double the price, but he said he’d always believed there was a mission for it. He would cut her a deal — no money down, 4 percent interest over 20 years and he would delay the first payment.

Besides, he said, it had drug addicts squatting on it. It was a mess.

As she signed the papers in May 2012, Kowall wondered whether she was crazy. The property was a junkyard with five mobile homes — some completely ransacked. There were rodent droppings, and it was crawling with bugs. The windows were broken. There were holes in walls and ceilings. Wiring had been stripped.

One board member threatened to resign if she went through with it — and ultimately did.

But Kowall saw potential and had faith. “I could see it even through all the filth and garbage,” she said.

She kicked out the squatters and moved into the bigger house, before she even had locks on the doors.

She could hear rats scurrying in the rafters, and drunks or addicts sometimes came back to try and stay.

It was scary, she said. For a while, she’d discover things stolen. But that dissipated as she recruited volunteers and donors and cleaned up the property, put in doors, windows and locks and more recently, security cameras.

A local branch of Keller Williams Realty held a volunteer day. Home Depot Foundation gave her a $20,000 grant, and Sherwin Williams donated paint. People and companies — from window installers and contractors to plumbers, electricians and the Girl Scouts — donated materials, expertise and time.

They tore down one mobile home, restored the other homes and spent months in a daily race with the tide to pull a half-sunken boat out of the water. They turned a broken pontoon boat into a floating dock, built a second dock with donated materials and professional labor, brought in six truckloads of dirt to even out the property, put in crushed shell walkways and planted grass and flowers.

One day, she looked out over her piece of waterfront and saw what she had drawn on paper long ago: a place of meditation with a pergola and fire pit and all measure of dedications to men and women who serve – most especially her son.

Anyone who served is welcome – from first responders to the Armed Forces. They can come for an hour or two or for weeks on end, enjoying fully furnished one bedroom units, painted with the colors of the sea for $45 a night or $225 a week.

For some, it is a brief escape; for others, it is a port in a storm.

“It’s a place to get back on your feet,” said Holly Winn, a teacher and first responder who, after losing her job, moved in with one of her children. She found a new job but didn’t have enough saved for her own apartment and wandered into My Warrior’s Place. Kowall told her she qualified to live there.

Winn came for the accommodation but soon cherished her host’s wisdom. Winn’s son was about to deploy for the first time. Mother to mother, Kowall helped her come to terms with the terror of that.

Winn said she drinks her morning coffee on her screened back porch facing the water, watching the mullet jump and listening to the cacophony of birds. “Every morning we have a whole world out here singing,” she said. “You just can’t not be happy.”

A place for warriors

Kowall and Sims held several grief retreats at My Warrior’s Place. They soon realized they needed a larger building, where veterans attending the retreats could stay under the same roof. They set about raising money to build it on the property and broke ground in March.

Then in early 2014, Sims suddenly fell ill with congestive heart failure and died.

Tragedy on top of tragedy, Kowall said. Things often happen that way. But in a world where grief — and healing — are always present, she found a way to continue the work, with help from a veteran who went through the first program and was a career military social worker.

“You never get over it,” she said. “It’s learning how to carry it a little bit easier, to weave that tragedy into your life.”

She can teach from experience. Small things like figuring out how to answer the question, “How many children do you have?” (She says three: one in heaven, two still on earth). And big things like how grief rips families apart. Some marriages dissolve. Kowall is estranged from one of her daughters.

One person dies and it has all these effects, she said. “It’s just a catastrophic event that reaches on forever.”

But at this place on the water that she named for her warrior, Kowall heals.

Barely a day goes by that someone new doesn’t walk into her life. “My friendships with people since his death have been much more fulfilling, deeper,” she said.

“I’ve never worked harder in my life,” she said. “And yet financially to be so poor, I feel so rich.”

What can I do for you?

As she told her story, a man wandered behind the house and knocked on the screen door. His name was Bill and he was retired Navy. He’d been wanting to check out the place for a while, he said.

Kowall offered him a seat on the porch. “Hi Bill,” she said. “What can I do for you?”

“Actually,” he said, perching on a porch stair. “I want to know what I can do for you.”

Cahn.dianna@stripes.com Twitter: @DiannaCahn